Don't ask for a big pay rise, warns Bank of England boss

- Published

Bank of England boss: 'Don’t ask for a big pay rise'

Workers should not ask for big pay rises, to try and stop prices rising out of control, the Bank of England governor has told the BBC.

Prices are expected to climb faster than pay, putting the biggest squeeze on household finances in decades.

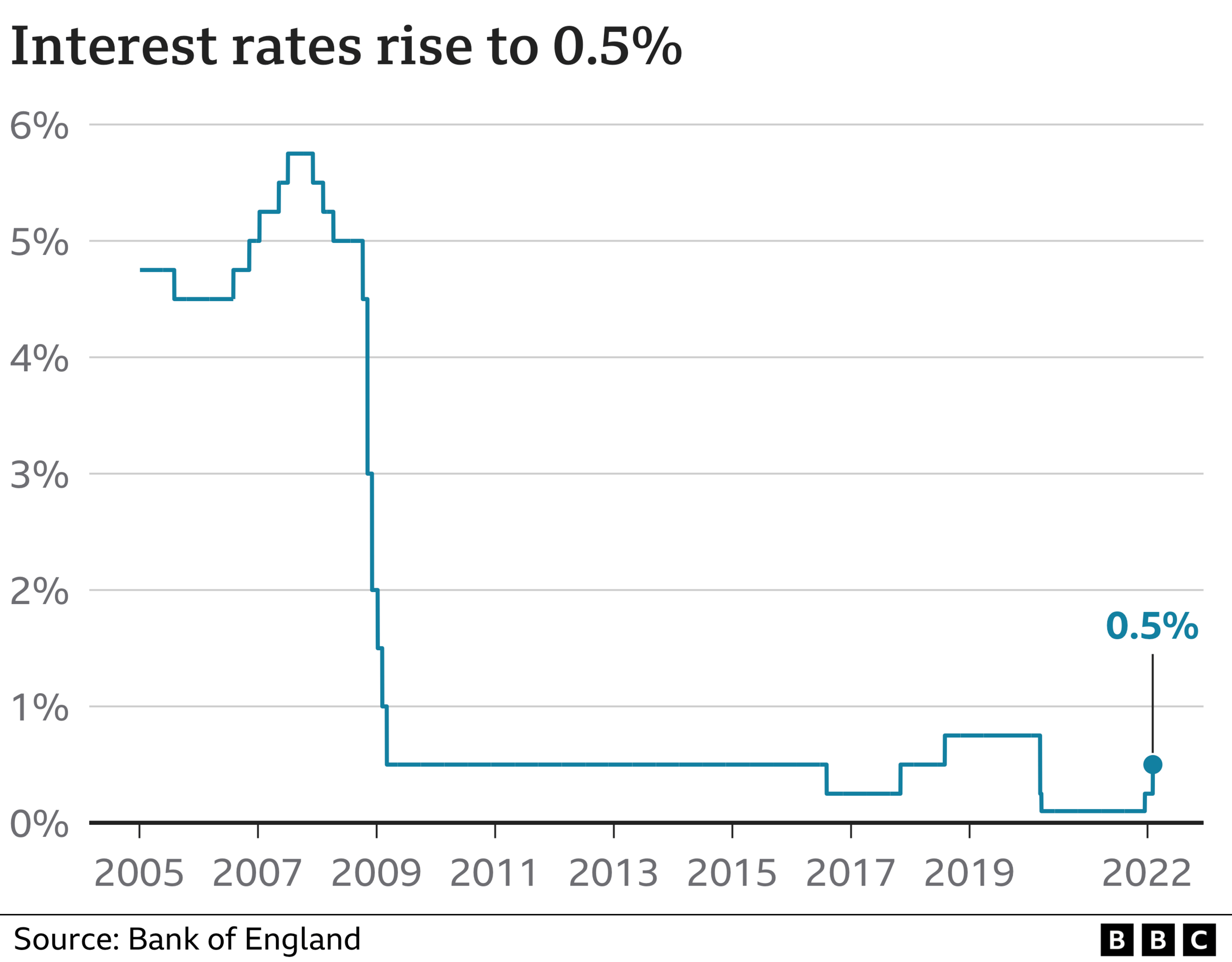

Andrew Bailey said the Bank raised rates to 0.5% from 0.25% to prevent rising prices becoming "ingrained".

Asked if the Bank was also implicitly asking workers not to demand big pay rises, he said: "Broadly, yes".

Inflation is on course to rise above 7% this year, leaving households facing the biggest income squeeze in decades.

Post-tax incomes are forecast to fall 2% this year, after taking into account the rising cost of living.

This represents the biggest fall in living standards since records began in 1990.

Mr Bailey said that while it would be "painful" for workers to accept that prices would rise faster than their wages, he added that some "moderation of wage rises" was needed to prevent inflation becoming entrenched.

"In the sense of saying, we do need to see a moderation of wage rises, now that's painful. I don't want to in any sense sugar that, it is painful. But we need to see that in order to get through this problem more quickly," he added.

Workers are currently enjoying pay rises of just below 5% on average, according to a Bank survey.

However, in sectors with big labour shortages, such as IT, construction and engineering firms have started paying workers "ad-hoc" bonuses in order to keep them.

In the year from 1 March 2020, Mr Bailey was paid £575,538 including pension.

That is more than 18 times higher than the median annual pay for full-time employees of £31,285 for the tax year ending 5 April 2021.

Inflation, as measured by the consumer prices index (CPI), is expected to peak at 7.25% in April, and average close to 6% in 2022.

This would be the fastest price growth since 1991 and is well above the Bank's 2% target.

There are also increasing signs of broader price pressures across the economy.

Prices of household appliances such as fridges climbed almost 10% over the past year.

Goods shortages also meant retailers were offering fewer bargains in the January sales compared with previous years.

The price of services such as getting a haircut or a trip to the vet had also become more expensive as companies passed on higher wage costs to consumers, the Bank warned.

Mr Bailey described the jobs market as "extraordinarily tight", adding that labour shortages were the "first, second and third thing people want to talk about" when he visited businesses across the country.

The Bank's Monetary Policy Committee that sets interest rates suggested that further rate rises would be needed "in the coming months" if the economy continued to bounce back from the slowdown caused by the Omicron variant,.

However, Mr Bailey cautioned that the economic outlook was particularly "uncertain"

This may not necessarily be the start of a "long march upwards" in interest rates, he added.

The worst squeeze on the income of households since 1990 is what the Bank predicts.

Record energy bill rises from April will take inflation to a peak of 7.25% in April, more than treble the Bank's normal target.

Some have called it "Black Thursday" for living standards.

In raising interest rates again and signalling more rate rises in the coming months, and nearly voting for even more on Thursday, the Bank is putting the nation on the couch in an exercise in mass psychology.

Inflation rises can be self-fulfilling. If workers, consumers and businesses expect 7% rises to persist, they will pre-emptively put up prices and ask for wage rises that then bring this about.

What the Bank is trying to do is to confine what is happening right now to being a one-off shock.

To stop the inflation becoming "ingrained" as Bank governor Andrew Bailey put it today.

There is a presentational issue here.

In ordinary circumstances interest rates are raised to temper booming or bubbly growth - to take the punch bowl away from the party. But there is no punch bowl. There is no party.

In fact the Bank lowered its forecasts for growth of the economy to 3.75% from 5%, even though Omicron was not as damaging as feared.

The Bank's answer is that this series of rate rises will be enough to stop a spiral of inflation, but will not go so high as to kill off the recovery. It is a delicate balancing act indeed.

Related topics

- Published3 February 2022

- Published17 March 2022