How smart sensors can help us care for our houseplants

- Published

Jasmin Moeller says she was previously not very good at looking after houseplants

Jasmin Moeller has been buying more houseplants over the past two years - like millions of other people around the world.

With the pandemic meaning that most of us have spent much more time stuck at home, there has been a rush to bring more nature and colour inside, too.

For Ms Moeller, a 38-year-old from Germany, having extra plants in her apartment makes her feel "more comfortable". She adds: "They give me a good feeling. It is like having nature and a calm place at home."

In the UK, online indoor plant retailer Patch says sales soared 500% during the first year of the pandemic. , external This trend has continued - the latest figures from the Garden Centre Association show that 2021 houseplant sales were 29% higher than in 2020, and 50% up on 2019., external

It is a similar picture in other countries, with sales of houseplants in the US rising 18% last year,, external while those in Germany grew 11% in 2020., external

How often do you forget to water your houseplants?

Yet it is one thing to buy a new houseplant and quite another to successfully look after it, for her part, Ms Moeller freely admits that she is "not very good at taking care of them".

To help her and others who worry about their lack of green fingers, there has been a growth in the sale of hi-tech sensors for indoor plants - devices that you push into the soil next to them.

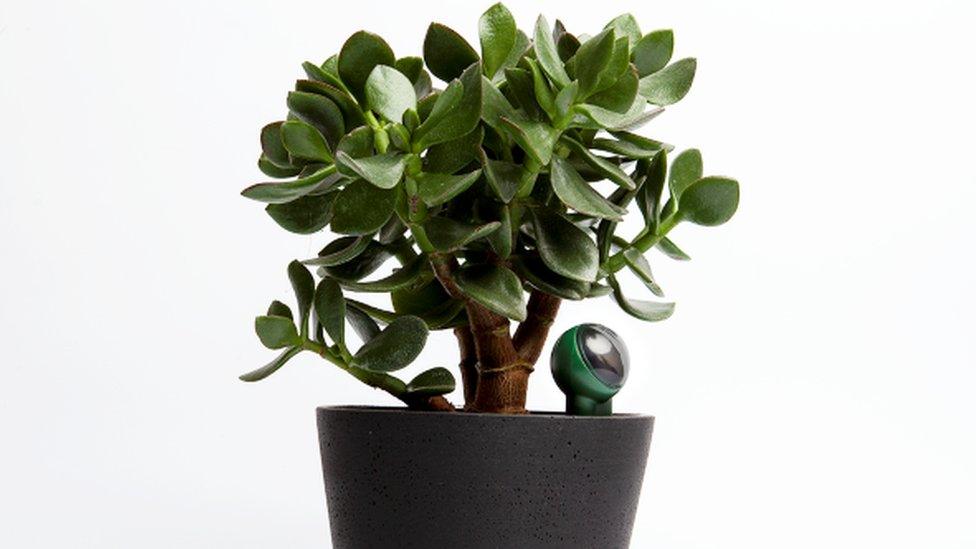

These sensors are usually solar powered and connect wirelessly by Bluetooth or wi-fi to a user's smartphone and laptop. They show in real time if a plant has enough water or sunlight, and the correct temperature.

Ms Moeller uses a sensor made by German firm Greensens for some of her plants. It has more than 5,000 species on its app database.

"It gives me the opportunity to monitor... and now my plants look healthy," says Ms Moeller, who gets sent regular notifications about how her plants are doing, and whether they need watering in particular.

The Greensens sensor uses solar power and connects to a smartphone app

The app uses an emoji traffic light system, with red, yellow and green smiley faces, to show the state of the plant. Red indicates the plant is very dry and dying, yellow is okay, while green indicates that it feels good and is in perfect condition.

Greensens is the brainchild of founder Stanislav Shults, who says the idea came from first-hand need as he used to be a "serial plant killer".

"The problem in having plants is the same as with a pet," says Mr Shults. "You really need a little knowledge about plant health to take care of them."

In its first year, 2020, Greensens sold €15,000 ($17,000; £12,600) worth of sensors. Since then its sales have trebled, and last year totalled €46,000.

Greensens users can link several sensors to one app

Dr Rumina Taylor, a clinical psychologist at UK practice HelloSelf, says it is not surprising that houseplant sales have risen during the uncertainty of the past few years.

"Research has shown that keeping even a single small plant close to you can improve stress and anxiety in as little as a few weeks," she says. "Plants bring a sense of calm, increase productivity and overall relaxation."

Another plant sensor firm is fellow German business Fyta, which is just about to release its technology onto the market. Its app includes additional content such as tutorials, so users can learn more about their plants.

It also allows users to identify plants via their cameras. "You can take a picture of the plant and it'll tell you exactly what kind of plant you have," says co-founder Sylvie Basler. "You can make an entire garden in your app."

Fyta's Sylvie Basler and Claudia Nassif (right) are just about to launch their plant sensor

But what do gardening experts think of such gadgets?

Botanist Silver Spence, chief executive at online plant retailer Friends or Friends, worries that people may never improve their gardening skills.

"A lot of keeping house plants is about tuning into the plant, its needs - and learning about them in your environment," she says. "By using these devices, you can learn along with the gadget - if it works well - or you can choose to rely on the gadget forever."

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

Ms Spence also wonders if solar powered sensors will get enough light in gloomy UK or Scandinavian rooms during winter time.

"All that aside, I admire the technology behind digitising one of the last offline hobbies."

The Fyta sensor also connects to an app on your mobile phone

David Angelov, chief executive of US gardening website PlantParenthood, also recommends people establish their own sense of what a plant needs. He wants them to become the sensor themselves.

"If a plant has a lot of leaves, it's using a lot of energy to grow," he says. "It should [typically] be watered once a week.

"To test if there's enough water, take some soil in your hand and make a fist or ball out of it. If it leaks water like a sponge, it's too wet. If the soil doesn't stick together like a snowball, it's too dry.

"For light, if the greener leaves are turning yellow, that's not enough light. If it's bright green, it's a happy plant."

Back in Germany, Ms Moeller says she is sure that the sensors are helping her to improve her gardening knowledge and skills. "Recently, my neighbour said I was very good at taking care of my plants."