Five ways the Ukraine war could push up prices

- Published

Severe sanctions on Russia aim to isolate the country and create a deep recession there, but the economic fallout will also be felt by people around the world.

The sharp rise in the prices of things from oil and metals to wheat is expected to push up the cost of many everyday items from food to petrol and heating.

1. It might cost (even) more to heat your home

Russia is the world's largest natural gas exporter, which is vital for heating homes

People in the UK and Europe are already paying high prices for energy and fuel.

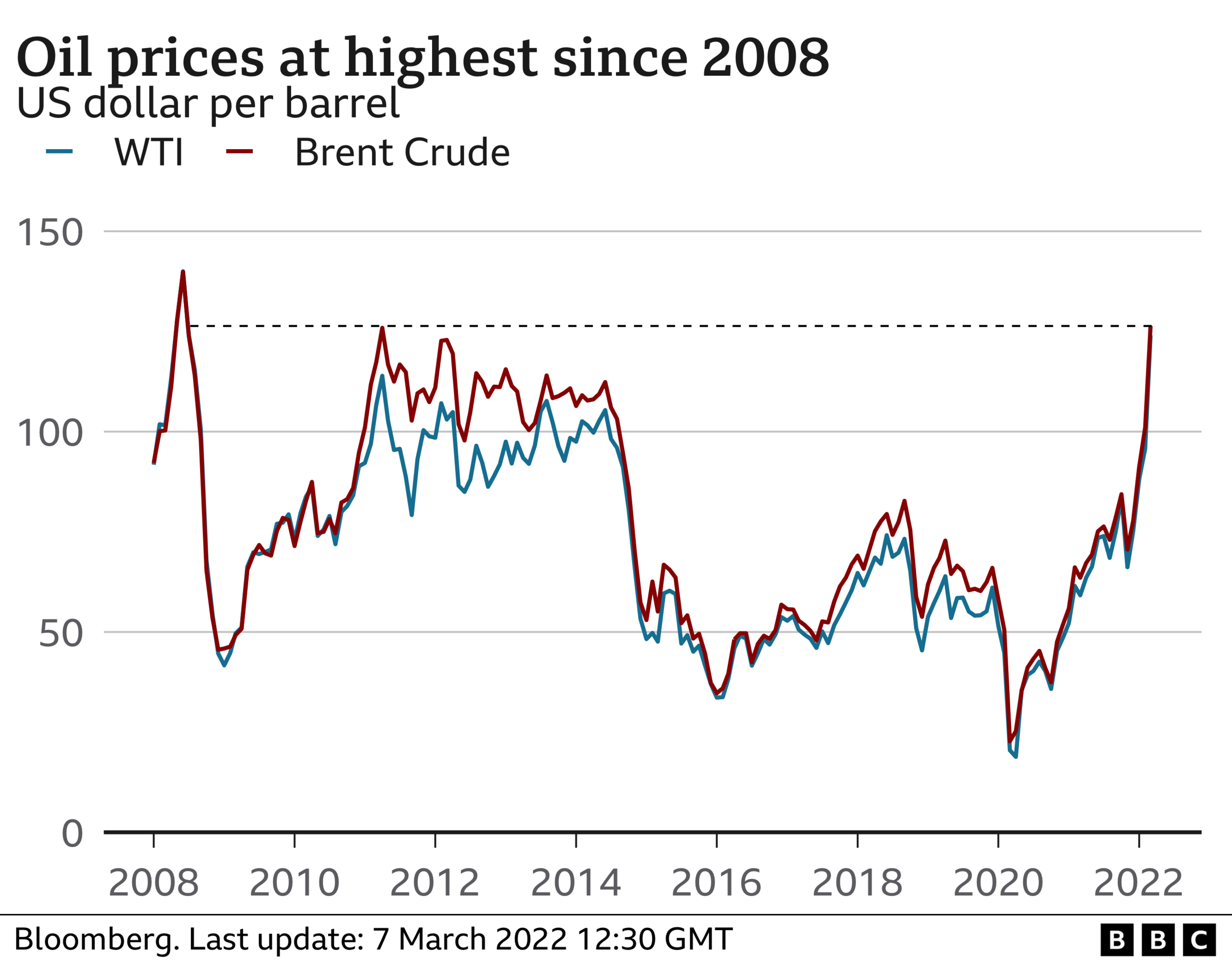

The Russia-Ukraine conflict has so far driven these even higher and caused the price of oil to jump to level in almost 14 years, while wholesale gas prices have more than doubled.

If gas prices stay at that level, energy analysts have warned that household fuel bills in the UK could reach as much as £3,000 a year, while average UK petrol prices have repeatedly hit record highs, with the latest price at 155p and diesel at 161p.

Russia is the second-biggest exporter of crude oil, and the world's largest natural gas exporter, which is vital to heating homes, powering planes and filling cars with fuel.

The UK gets only 6% of its crude oil and 5% of its gas from Russia, but the EU sources nearly half of its gas from the country.

If one country reliant on Russian supplies receives less gas, they have to replace it, impacting the supplies of gas for other countries - that's why British energy prices and bills are still affected in a similar way to European ones.

There are fears President Vladimir Putin might "weaponise" Russia's natural resources by reducing supplies of gas to Europe in response to sanctions. Politicians in Germany are calling for a "national gas reserve" to be created to protect consumers from price shocks.

Meanwhile, the US is discussing a potential ban on buying Russian energy which has also fuelled price rises.

Plane fuel is also linked to the price of crude oil and Ryanair boss Michael O'Leary has warned tickets for this summer will be higher than 2019, partly because of the rise in the price of oil.

2. Your food shop could cost more

Tinned goods could rise further if aluminium prices remain high

UK food producers don't import many items from Russia or Ukraine, but prices here may still rise because of an increase in associated costs, such as tinned cans and packaging and transport.

Meanwhile, the cost of everyday food items might rise in places like Turkey and North Africa, which rely on wheat and corn from Ukraine and Russia.

Both countries, once dubbed "the breadbasket of Europe", export about a quarter of the world's wheat and half of its sunflower products, like seeds and oil. Ukraine also sells a lot of corn globally.

Analysts have warned that war could impact the production of grains and even double global wheat prices.

More than 40% of Ukraine's wheat and corn exports went to the Middle East or Africa last year - and disruptions to supply could affect availability in these areas.

The UK, by contrast, typically produces more than 90% of the wheat consumed in the country. But farmers here might find themselves paying more for fertiliser, which is one of Russia's biggest exports.

3. Your mortgage repayments may rise

Homeowners in the UK would see mortgage repayments rise if the Bank of England's base rate went up

Inflation, which measures how fast the cost of living rises over time, hit 7.5% in January in the US - the highest level seen there since February 1982 - and rose by 5.5% in the UK.

But one economist has warned it could rise close to 10% in major Western economies if the cost of energy and food is pushed up by dwindling supplies cause by the Russian-Ukraine conflict.

Such a figure might encourage the Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve to increase interest rates. The idea is that when borrowing is more expensive, people will have less money to spend. As a result, they will buy fewer things, and prices will stop rising as fast.

But in the UK, for example, about 2.2 million homeowners with mortgages linked to the Bank of England's base rate would see repayments go up, putting further pressure on household budgets that are already being squeezed by the cost of living.

4. Your pension might fluctuate - but don't panic

Widespread falls in share prices, such as those triggered on Thursday, are likely to be bad news for pension savers

Russian stocks crashed by as much as 45% in the wake of the Ukraine invasion with trading subsequently suspended, with banks and oil companies among the worst affected.

It also led to steep falls on stock markets elsewhere around the world: in Europe the UK's FTSE 100 index has fallen over 6% since Russia crossed into Ukraine while Germany's Dax index is nearly 10% lower.

Many people's reaction to stock market changes is that they are not directly affected, because they don't invest money in stocks and shares. But there are millions of people with a pension whose savings are invested in the stock market.

If widespread falls in share prices are sustained then it's likely to be bad news for pension savers because the value of their savings pot is influenced by the performance of investments.

Some investors or savers might look to protect their money or assets by moving them to traditional "safe havens", like gold, especially as the markets are likely to see more volatility as the crisis develops.

But pension savings, like any investments, are usually a long-term bet and advisers say it's important not to panic about short-term movements up or down.

5. DIY and cars could cost more

Canned goods may become more expensive if metal price rises persist, the LME chief executive said

As a leading commodities exporter, Russia is one of the world's largest suppliers of metals used in everything from aluminium cans, to copper wires, to car components, such as nickel, which is used in lithium-iron batteries, and palladium, which is used in catalytic converters.

Everyday goods - which may seem far removed from the conflict - may rise as a result of it.

"When you buy your drinks can made of aluminium, or when you make renovations to your house and you need copper for your wiring, all of those prices do go into the overall inflationary pressure," the boss of the London Metals Exchange has warned.

If Vladimir Putin decided to cut off supplies of these metals in retaliation to sanctions, existing supply problems could worsen, with car firms having to find alternative sources.

Russia is also home to manufacturing hubs for brands like Stellantis, Volkswagen and Toyota. Some production has already been paused at Russian car plants, while shipping and delivery companies halting activity to and from the country is likely to impact the availability of new cars.

Related topics

- Published24 February 2022

- Published24 February 2023