Ukraine crisis: What sanctions could West still impose on Russia?

- Published

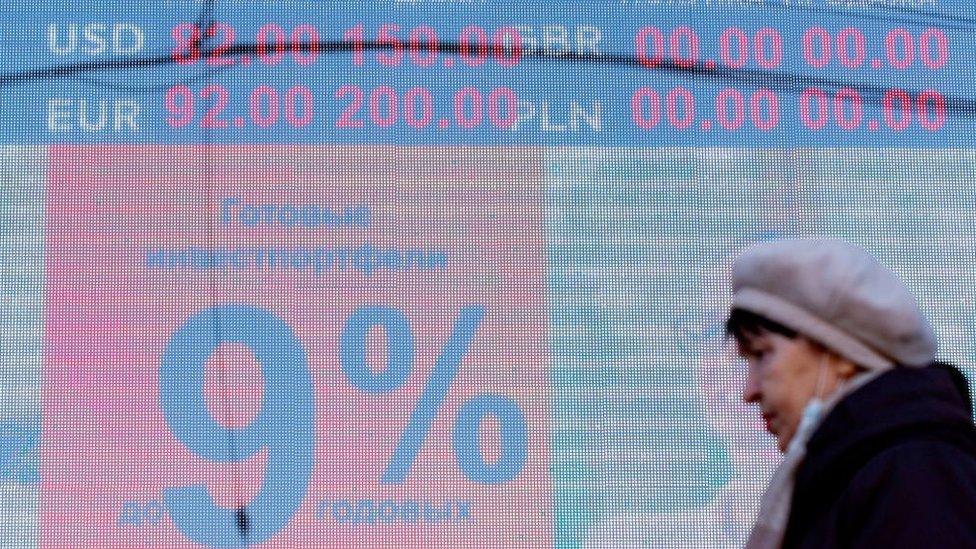

The Russian rouble dropped precipitously last week

A raft of actions by the West is aimed at choking Russia's economy and banking system, and punishing Vladimir Putin's inner circle. What more sanctions could they impose?

In response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the US, UK, EU and more than two dozen other nations retaliated with economic measures that have sent the Russian rouble tumbling, cut major Russian banks from the global financial system and hurt state-owned firms and oligarchs, including Mr Putin himself.

The US says its actions hit 80% of banking assets in Russia; and the EU 70%. The allies have also taken steps to limit Russia's access to key technology, such as microchips and lasers; and moved against cryptocurrencies.

Together, they represent the toughest sanctions Mr Putin's Russia has ever faced.

And analysts expect policymakers to continue tightening - for example, by adding more kinds of technology and new companies to blacklists. The most recent action by the US, on Wednesday, targeted oil refining equipment, among other steps.

"We are at a seven or eight out of 10 on the escalation ladder right now," said Emily Kilcrease, senior fellow and director of the Energy, Economics and Security Program at the Washington think tank, the Center for New American Security. "There is definitely still room to go with tightening."

Energy exception

Many Western companies, including BP, Apple and others have responded to the situation by taking steps to halt services or exit the country.

But for now, trade can still flow - not least key exports like oil and gas, for which Russia is a major global supplier.

Western policymakers have been reluctant to hit energy, in part for fear of causing a spike in energy prices that would cause economic damage at home as well - especially in Europe, which relies on Russia for roughly 40% of its gas imports and roughly 30% of its oil imports.

But as the violence in Ukraine has escalated, there is growing pressure on the US and Europe to act.

Will the West target Russian oil and gas exports for sanctions?

"My sense is that it's going to become politically untenable to say we'll keep paying Russia for oil, gas and coal," says Christopher Miller, professor at Tufts University's Fletcher School and an expert on the Russian economy.

"That's already been politically tough for Western leaders to stand by and I think it's going to become even tougher as the Russian military escalates its use of force."

It's a tricky calculus.

While oil and gas transactions are key to preventing the Russian economy from going "off a cliff", cutting off that lifeline risks provoking more extreme reaction by Russia, says Jeffrey Schott, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a Washington think tank.

"The level of economic pressure now is severe. If you go for the economic jugular, Putin may respond with cyber and military action that will only make the suffering worse," he says.

What's more the commitment, announced by Western allies this week, to release a 60m barrels of oil from strategic national reserves - half of which will come from the US - will only act to soften a temporary spike in prices.

Russia may be able to withstand the loss of Western buyers, if it can sell less on the global markets at a higher price, says Ms Kilcrease.

"People I think want to see something there... but you have to think about the effect of what cutting off those sales would actually be. Will it hurt Russia? It's not actually clear," she says.

Immediate pain

The sanctions have already caused economic havoc in Russia.

Before closing this week, the two major Moscow stock indexes plunged more than 20%. The rouble has dropped to record lows against the dollar, hurting the purchasing power of Russian families at a time when rising prices and deteriorating standard of living were already concerns.

The war has sparked protests in Russia, which has also seen the standard of living slide in recent years

The consultancy Capital Economics recently estimated that the sanctions could shrink Russia's economy by 15% this year.

Nor has the pain been limited to Russia.

Global oil prices have already risen more than 10% since the start of February amid the tensions - and analysts expect they will remain elevated due to uncertainty from the conflict. Ukraine and Russia also supply nearly 30% of the world's wheat, 19% of its corn and 80% of its sunflower oil.

Currencies in countries with close ties to Russia, like Kazakhstan, have also been hit.

"That's the problem with sanctions - they never just end up targeting only one place," says Kristy Ironside, professor of Russian and Soviet history at McGill University. "They tend to have other knock-on effects so anything [policymakers] do next, they have to consider very carefully in light of that."

Russia attacks Ukraine: More coverage

THE BASICS: Why is Putin invading Ukraine?

RUSSIA: Watching the war on TV

IN DEPTH: Full coverage of the conflict

Nor is it clear how economic destabilisation will affect Mr Putin's standing at home - or if they will make him willing to negotiate a political end to the violence in Ukraine.

After all, Russians have endured economic isolation before and the ability to afford international travel and imported cheese may not matter much to his base.

"As long as pensions keep getting paid and people can enjoy a relatively reasonable standard of living... I think there's some leeway," Prof Ironside says. "If this is sustained... I don't know."

Prof Miller says he is not optimistic that the sanctions will force Mr Putin to negotiate over Ukraine. But if sustained, he says, they may curb his power.

"Anything that touches the financial system is going to get more complicated and expensive as a result of this," Prof Miller says. "That will have a ripple effect throughout the Russian economy."

"It will make Russia's economic outlook over the next couple of years substantially dimmer and therefore make it harder for the Russian government to keep its domestic political situation under control while simultaneously waging a set of wars abroad."

"This is the goal," he adds. "To create this medium to longer term degradation of Russia's abilities."

- Published23 February 2024

- Published1 March 2022