Does it matter if we know where our food comes from?

- Published

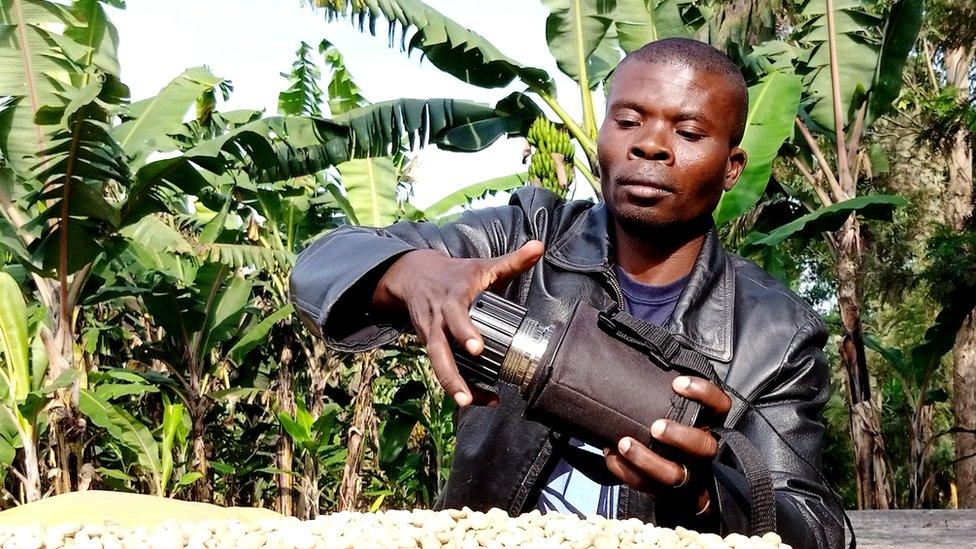

Faustin Mulomba's family has strong ties to the coffee business

"My parents were coffee growers, I am a coffee grower, I have known how to handle coffee since my birth," says Faustin Mulomba, from Bweremana in the west of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo).

Mr Mulomba has spent most of his life working in coffee cultivation, but last year was put in charge of a coffee-washing station for the AMKA co-operative, a group of more than 2,000 farmers close to Lake Kivu.

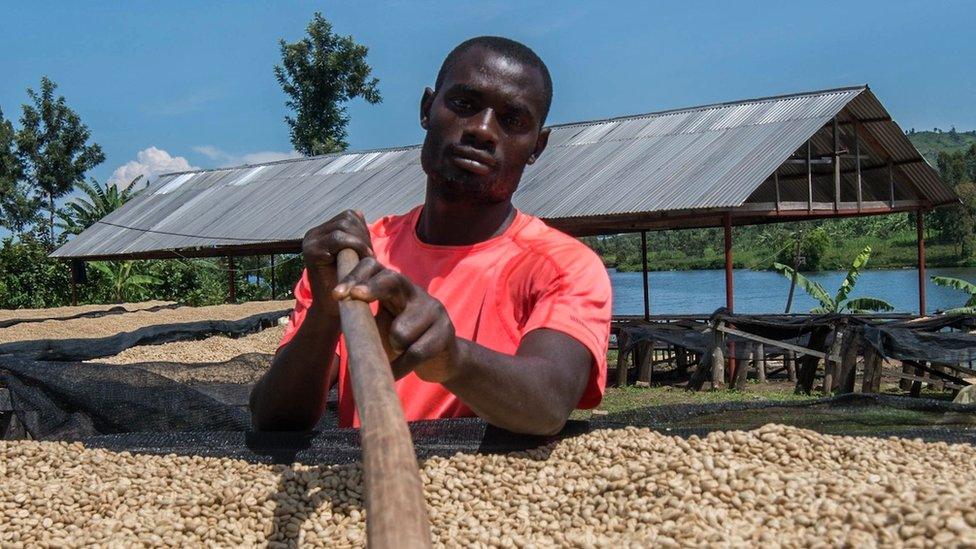

Here, beans from farms across the region have their outer skin and pulp removed. They are washed, sorted and dried, before being sent to the city for further processing.

Up to 120,000kg of coffee cherries pass through his station in a year, which amounts to a little less than a container full of green coffee beans.

While Mr Mulomba's family has a long history in coffee production, the introduction of new technology has changed the way he looks at the business.

Now, when beans from his co-operative are sold to Nespresso, the company uses sophisticated data capturing and storage methods - including blockchain technology - to track the beans as they move from the farm to the customer.

Workers track the coffee using a smartphone app

Blockchain is a digital ledger, or a log, of transactions. The information is distributed and stored among a network of users. The idea behind using the ledger is to make the information easy to verify, but difficult to manipulate.

In practice, Mr Mulomba uses a simple smartphone app to scan QR codes that give him information about a particular bag of coffee, such as the weight and pulping data.

For Mr Mulomba, the new tech means he can see how much coffee has been produced in the co-operative, where the coffee is and if it has been handled correctly.

"It is a good tool because [...] it allows us to measure, or to have all the quantities supplied to the co-operative in real-time," he says.

Nespresso partnered with Australia-based start-up, OpenSC, a technology firm that specialises in food traceability. OpenSC has also worked with Austral Fisheries, using global-positioning system (GPS) data and sensors on fishing boats, to ensure vessels are not fishing in marine protected areas.

Chief executive and co-founder, Markus Mutz, says this system is a better than the alternative - manual spot-checks carried out by officials.

"Why would you trace something [in the first place] unless there's something about it that you can be proud of, or that is valuable?" he explains.

Coffee cherries have to go through multiple steps before they reach the cup

Retaining continuous data from the source of production can help improve the entire production process - preventing losses and bad practices.

But such tracing is not without its challenges. Like any process that requires a database, the quality of the information being fed-in is critical to its success. For instance, back in DR Congo, when coffee is harvested at night, there can be connection problems and delays in capturing the data.

Fairtrade International's Director of Global Impact, Arisbe Mendoza, says tracing technology unlocks opportunities for monitoring and supporting fair treatment and pay for workers across the supply chain.

The organisation would like to see more traceability in international trade.

Yet, she echoes Mr Mulomba's concerns, Ms Mendoza says: "My experience for some of the initiatives that we have had in the system is that technology is not the issue, it is the capacity building that we need to do behind this to ensure that producers and everyone in the supply chain who will be using these tools, is understanding and able to use it fully."

She says producers and farmers need to have full access and use of the data in the supply chain, to negotiate prices, prove compliance, and access markets. But often this is not the case, or data rights are unclear.

This tracing system uses QR codes to hold information about the coffee

"Producers might have access to information, but not necessarily the rights to it. We need to ensure that they own the data, then they also can make use of the data anyway they want."

Sara Eckhouse, executive director of FoodShot Global, a food system investment platform, says not being able to trace food fuels consumer distrust and can even perpetuate bad labour practices, or lack of sustainability.

However, she is concerned that the costs and logistical difficulties of traceability will end up being pushed back to the producers. She also cautions that adding marketing around traceability to products could be more confusing than helpful for shoppers - who are already faced by a variety of supposedly sustainable labels.

"If each company is still going to have their own standards that they're verifying for, and if there's no uniform standard or expectation that everybody is meeting a minimum, you could still have companies making claims like 'blockchain verified sustainable', but what does that actually mean?"

Shalini Unnikrishnan, is managing director and partner at the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), which supports a variety of projects working on food tracing, including at OpenSC. She says consumers are increasingly willing to change their food shopping habits for more sustainable products, including paying more money for certain items.

Mrs Unnikrishnan adds that while across the so-called 'digital agriculture' sector, there are lots of small exciting companies and pilots popping-up, policy frameworks are needed to scale these businesses up.

"I think regulation standards are really fundamental to make sure that the changes happening, are happening at scale," she says, because these provide companies, farmers and buyers "a signal of what is required and a framework for standards."

A key question for companies such as supermarket chains, is how much customers will care where their produce comes from

So, what do customers think?

German management consultant, Thomas Kunze, is a coffee lover who enjoys buying locally-sourced beans on his international travels. Quality and sourcing from interesting locations is important to him. He recently bought some limited edition coffee pods that display the traceability tool.

When Mr Kunze scans the package's QR code, he sees which area, or cooperative, his coffee came from, including the profiles of some of the farmers and whether they have been paid for their produce.

"It is interesting but not important," he says about seeing the journey his brew took. "Traceability is nice to see but, because I don't know anything about the different locations, I would need more information about the steps and locations."

Back in DR Congo, Mr Mulomba cheerily invites coffee drinkers to visit. "It is very important that the consumers render us visits, [then] maybe they will know our reality on the ground."