War in Ukraine: Russia says it may cut gas supplies if oil ban goes ahead

- Published

- comments

The Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline was inaugurated just over a decade ago

Russia has said it may close its main gas pipeline to Germany if the West goes ahead with a ban on Russian oil.

Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak said a "rejection of Russian oil would lead to catastrophic consequences for the global market", causing prices to more than double to $300 a barrel.

The US has been exploring a potential ban with allies as a way of punishing Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.

But Germany and the Netherlands rejected the plan on Monday.

The EU gets about 40% of its gas and 30% of its oil from Russia, and has no easy substitutes if supplies are disrupted.

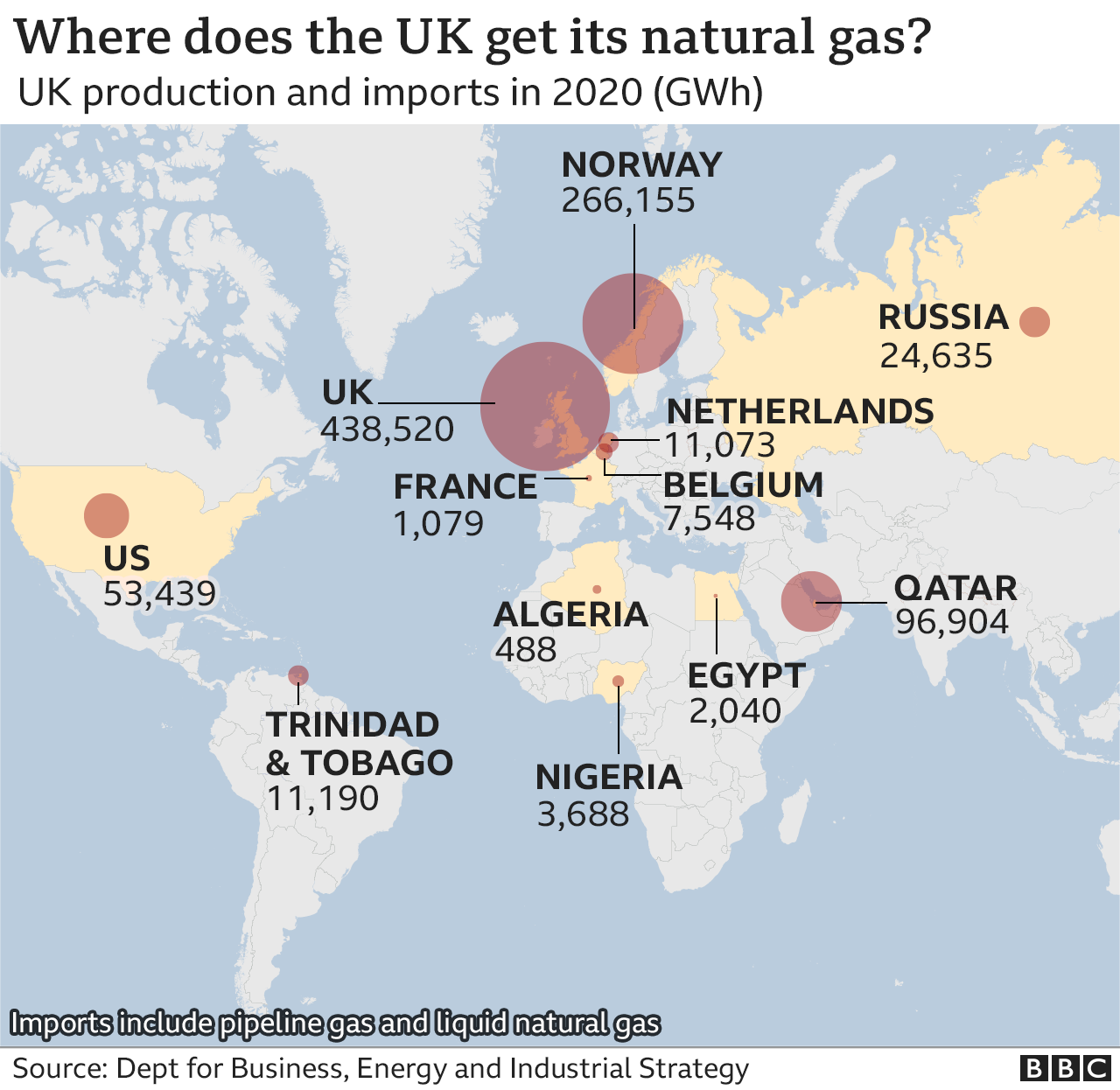

While the UK would not be directly impacted by supply disruption, as it imports less than 5% of its gas from Russia, it would be affected by prices rising in the global markets as demand in Europe increases.

Iain Conn, the former boss of British Gas owner Centrica, said natural gas was "less freely" traded compared to oil, and it would be "much more difficult" to replace Russian gas if supplies are affected as it is transported through fixed pipelines from country to country.

The price of Brent crude - the global benchmark for oil prices - rose to around $130 a barrel on Tuesday following reports that the US and UK will announce its own ban on Russian oil imports.

In an address on Russian state television, Mr Novak said it would be "impossible to quickly find a replacement for Russian oil on the European market".

"It will take years, and it will still be much more expensive for European consumers. Ultimately, they will be hurt the worst by this outcome," he said.

Pointing to Germany's decision last month to freeze certification of Nord Stream 2, a new gas pipeline connecting the two countries, he added that an oil embargo could prompt retaliation.

"We have every right to take a matching decision and impose an embargo on gas pumping through the [existing] Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline," he said.

Russia is the world's second largest gas producer and third largest oil exporter, and any move to impose sanctions on its energy industry would badly damage its own economy.

Nathan Piper, head of oil and gas research at Investec, said although imposing sanctions on Russia's oil and gas exports was attractive, "practically it is challenging".

He said both the global oil and gas markets were tight ahead of the war in Ukraine "with limited spare capacity to replace any disrupted Russian volumes".

"The question is now whether US and European leaders are prepared to endure high oil and gas prices to add energy exports to the sanctions list," he told the BBC.

"The threat of this action is almost the worst of both worlds, forcing prices up but doing nothing to limit Russian volumes or the revenues flowing to Moscow."

Analysts at Capital Economics have forecast oil prices could rise to $160 a barrel if the West imposed sanctions on Russian exports, but David Oxley, senior global economist at the consultancy, told the BBC it was disruption to Russian gas that would hit countries harder, describing it as a "completely different kettle of fish".

He said energy intensive industries across Europe could be hit, with "vast swathes of heavy industry being switched off" as it is much harder finding replacement gas suppliers compared with oil.

EU countries heavily reliant on Russian gas, such as Germany, could switch from gas to coal, he said, but that would run counter to the bloc's climate ambitions and would not be a long-term solution.

The energy markets have been supremely volatile over the past week, and understandably so. There are genuine fears that supplies of oil and gas from Russia could be cut off or disrupted.

Yet the response to Russia's suggestion it could close a major pipeline, depriving northern Europe of a large chunk of its gas supplies, has been pretty muted so far.

There are a couple of reasons for this. Firstly, Russia is threatening a tit-for-tat embargo - cutting off its gas exports if the West goes ahead with a ban on Russian oil.

But despite pressure from the US, such a ban is unlikely. European leaders have already poured cold water on the idea - so Russia's counter-threat carries relatively little weight.

And then there's the fact that Russia is still making huge sums from sales of oil and gas to Europe every day, helping to fund its war.

Moscow has everything to gain from exploiting traders' nerves to push up energy prices; but a great deal to lose if it were to carry out its threat.

Ukraine has implored the West to adopt an oil and gas ban, but there are concerns it would send prices soaring. Investor fears of an embargo drove Brent crude oil to $139 (£106) a barrel at one point on Monday - its highest level for almost 14 years.

Meanwhile, wholesale gas prices rose to 565p per therm early on Tuesday, but fell to 480p in the afternoon.

UK stock markets rose slightly in early trading after a volatile Monday caused by the US's discussions over a potential Russian oil and gas ban.

Early on Tuesday, nickel prices on the London Metal Exchange more than doubled to rise above the $100,000-a-tonne level for the first time, before trading in the metal was suspended.

Russia supplies the world with about 10% of its nickel needs, mainly for use in stainless steel and electric vehicle batteries.

Average UK petrol prices have hit a record 155p a litre

Quoting unnamed sources, Reuters news agency reported that the US might be willing to move ahead with an embargo without its allies, although it only gets about 3% of its oil from Russia.

However, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has dismissed the idea of a wider ban, saying Europe had "deliberately exempted" Russian energy from sanctions because its supply could not be secured "any other way" at the moment.

European powers have, however, committed to move away from Russian hydrocarbons over time, while some Western companies have boycotted Russian shipments or pledged to sell their stakes in Russian energy companies.

Mr Novak said that Russian companies were already feeling the pressure of US and European moves to lower the dependence on Russian energy, despite fulfilling all its contractual obligations to deliver oil and gas to Europe.

"We are concerned by the discussion and statements we are seeing regarding a possible embargo on Russian oil and petrochemicals, on phasing them out," he said.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

Jeremy Bowen was on the frontline in Irpin, as residents came under Russian fire while trying to flee.

- Published26 January 2023

- Published7 March 2022

- Published7 March 2022