Grieving families face extra fees and paperwork, says consumer group

- Published

Ruth Blakemore founded a death notification service after her father was overwhelmed by paperwork when his wife died

Grieving families face extra charges and a "bureaucratic nightmare" when informing financial firms of a loved one's death, a consumer group has said.

Fairer Finance found some investment companies continued to take fees until an account was closed, which could be months after the death.

A trade body admitted there were areas where the sector had "fallen short".

Nearly half of savings firms required families to call or visit a branch to inform them of a death.

Call for change

Fairer Finance found some investment companies refunded additional fees after a death was reported and others included charges in their headline fees.

A small number charged extra fees to pay money out of accounts when somebody died. While terms and conditions make this clear, the consumer group wants a change to the rules.

It said investment companies should only be allowed to charge what is needed to cover their own costs, and it also called for a ban on cancellation and account closure fees when somebody died.

Tim Fassam, director of policy at PIMFA - the Personal Investment Management and Financial Advice Association, said: "While we would expect personal investment firms to always seek to deliver superior consumer outcomes to their clients, there are clearly instances as highlighted by this report where they fall short."

He said that a new consumer duty, outlined by the regulator - the Financial Conduct Authority, should put more emphasis on providing fair value to customers.

"It should, however, be noted that winding up accounts does represent a cost to firms and while the circumstances of that closure are regrettable, it is not unreasonable for firms to seek to recover some of the costs incurred," he added.

'We found Dad crying'

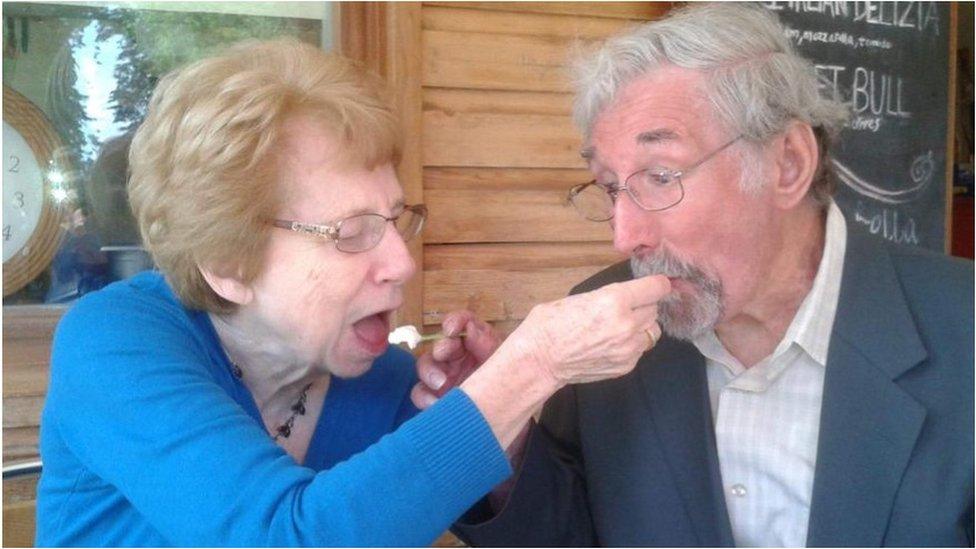

Pat and Ken Blakemore in happier times

The Fairer Finance report was commissioned by death notification service Life Ledger, external - a business set up by Ruth Blakemore. She was inspired to do so after the experiences faced by her dad, Ken, and her family following the death of her mum, Pat, in 2016.

"We found Dad crying," she said. "We'd never seen him cry like that before, not even when Mum died. He was surrounded by paperwork and opened up to us with some difficulty about the [previous] couple of days.

"Dad had started the process of notifying relevant organisations of mum's death. He'd got hold of solicitors, and found a copy of her will. Then he tried to contact the building society. This poor old man stood alone in line for quite a while, as it was lunchtime, and when he reached the front of the queue he was told he had to make an appointment to meet in person and he was sent away.

"Then he contacted her pension company. They didn't answer the phone for a while and when they did they gave him a different number to ring - a 'dedicated bereavement helpline'. The helpline was closed for the day. He contacted her mobile phone company. After holding for half an hour he gave up, and that's when we found him."

The family stepped in to help her father, now aged 91, who she described as a "straightforward Yorkshireman who takes money matters seriously". He had been determined to handle his late wife's affairs, but had come up against "a complex mountain of admin".

Additional costs

In addition to investment accounts, the report suggested there was little incentive for financial services companies to act quickly and efficiently when notified of a death.

The consumer group said it cost families millions of pounds a year through ongoing charges for unused services, such as subscriptions, as well as unclaimed savings and pension funds where paperwork and account details had been lost.

It described the notification process as "antiquated and very paper-based", with many companies requiring families to send an original death certificate.

Most had no digital option for reporting a death. This left people having to wait on phone lines or queue in a branch at 22 of 49 savings providers, including High Street banks and building societies, to report the death of a loved one, it said.

"Managing a loved one's affairs when they die shouldn't be a bureaucratic and traumatic nightmare. In the 21st century, we should be making better use of technology to simplify the process and to remove some of the burden on families who are grieving," said James Daley, managing director of Fairer Finance.

He called for the creation of digital death certificates.

The Tell Us Once service, external helps families to inform public services of the death of a loved one with a single notification. The information is shared across HM Revenue and Customs, for tax issues, as well as departments dealing with benefits, state pensions, passports, and driving licences.

Some banks are part of a similar scheme, called the Death Notification Service, external, although the report said that the private sector was more "fragmented" in this area.

Related topics

- Published24 March 2022

- Published26 September 2020