Could contact lenses be the ultimate computer screen?

- Published

Smart contact lenses promise to bring data directly into your field of view

Imagine you have to make a speech, but instead of looking down at your notes, the words scroll in front of your eyes, whichever direction you look in.

That's just one of many features the makers of smart contact lenses promise will be available in the future.

"Imagine... you're a musician with your lyrics, or your chords, in front of your eyes. Or you're an athlete and you have your biometrics and your distance and other information that you need," says Steve Sinclair, from Mojo, which is developing smart contact lenses.

His company is about to embark on comprehensive testing of smart contact lens on humans, that will give the wearer a heads-up display that appears to float in front of their eyes.

Contact lenses might be able to give you useful information

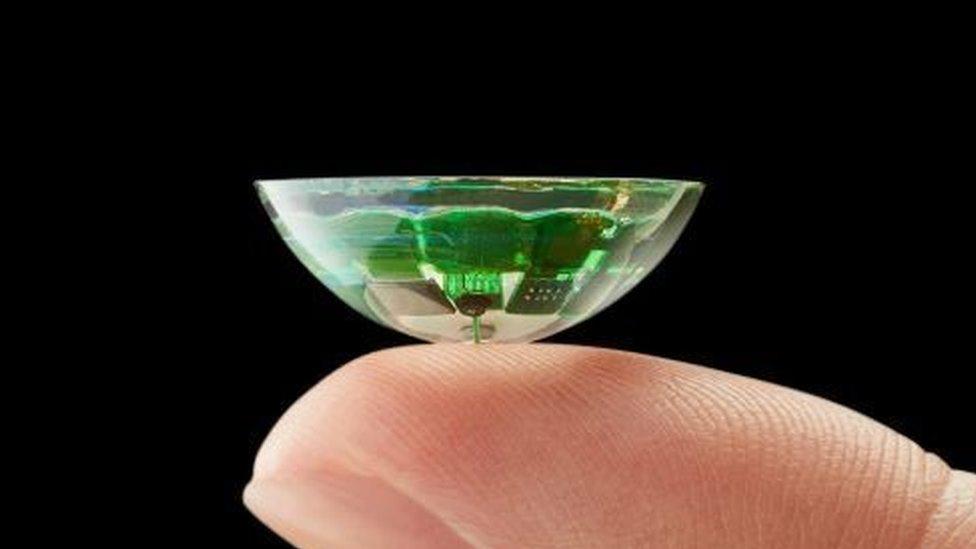

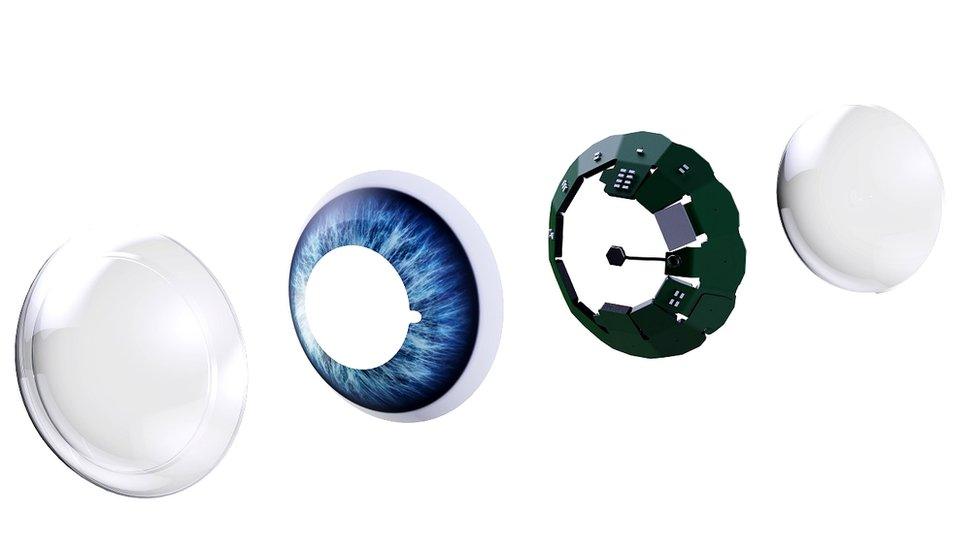

The product's scleral lens (a larger lens that extends to the whites of the eye) corrects the user's vision, but also incorporates a tiny microLED display, smart sensors and solid-state batteries.

"We've built what we call a feature-complete prototype that actually works and can be worn - we're soon going to be testing that [out] internally," says Mr Sinclair.

"Now comes the interesting part, where we start to make optimisations for performance and power, and wear it for longer periods of time to prove that we can wear it all day."

Other smart lenses are being developed to collect health data.

Lenses could "include the ability to self-monitor and track intra-ocular pressure, or glucose," says Rebecca Rojas, instructor of optometric science at Columbia University. Glucose levels for example, need to be closely monitored by people with diabetes.

"They can also provide extended-release drug-delivery options, which is beneficial in diagnosis and treatment plans. It's exciting to see how far technology has come, and the potential it offers to improve patients' lives."

Research is underway to build lenses that can diagnose and treat medical conditions from eye conditions, to diabetes, or even cancer by tracking certain biomarkers such as light levels, cancer-related molecules or the amount of glucose in tears.

A team at the University of Surrey, for example, has created a smart contact lens that contains a photo-detector for receiving optical information, a temperature sensor for diagnosing potential corneal disease and a glucose sensor monitoring the glucose levels in tear fluid.

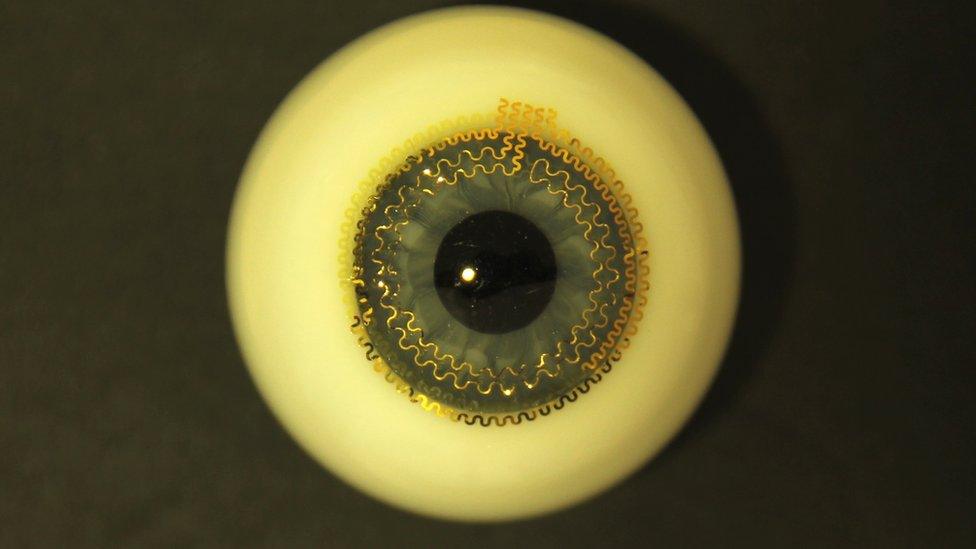

The contact lens developed by the University of Surrey can monitor the wearer's health

"We make it ultra-flat, with a very thin mesh layer, and we can put the sensor layer directly onto a contact lens so it's directly touching the eye and has contact with the tear solution," says Yunlong Zhao, lecturer in energy storage and bioelectronics at the University of Surrey.

"You will feel like it's more comfortable to wear because it's more flexible, and because there's direct contact with the tear solution it can provide more accurate sensing results," says Dr Zhao.

Despite the excitement, smart lense technology still has to overcome a number of hurdles.

One challenge will be powering them with batteries these will obviously have to be incredibly tiny, so will they deliver enough power to do anything useful?

Mojo is still testing its product, but wants customers to be able to wear its lenses all day, without having to recharge them.

"The expectation [is] that you are not consuming information from the lens constantly but in short moments throughout the day.

"Actual battery life will depend on how and how often it is used, just like your smartphone or smartwatch today," a company spokesperson explains.

Google Glass - launched in 2014 - didn't take off

Other concerns over privacy have been rehearsed since Google's launch of smart glasses in 2014, which was widely seen as a failure.

"Any discreet device with a forward-facing camera that allows a user to take pictures, or record video, poses risks to bystanders' privacy," says Daniel Leufer, senior policy Analyst at digital rights campaign group, Access Now.

"With smart glasses, there's at least some scope to signal to bystanders when they are recording - for example, red warning lights - but with contact lenses it's more difficult to see how to integrate such a feature."

Aside from privacy worries, makers will also have satisfy worries over data-security for the people wearing the lenses.

Smart lenses can only fulfil their function if they track the user's eye movements, and this plus other data could reveal a great deal.

"What if these devices collect and share data about what things I look at, how long I look at them, whether my heart rate increases when I look at a certain person, or how much I perspire when asked a certain question?" says Mr Leufer.

"This type of intimate data could be used to make problematic inferences about everything from our sexual orientation to whether we're telling the truth under interrogation," he adds.

"My worry is that devices like AR (augmented reality) glasses, or smart contact lenses, will be seen as a potential trove of intimate data."

For its part, Mojo says all data is security-protected and kept private.

The Mojo contact lens incorporates a tiny screen

Additionally there are concerns about the product that will be familiar to anyone who wears regular contacts.

"Any type of contact lens can pose a risk to eye health, if not properly cared for or not fitted properly.

"Just like any other medical device, we need to make sure the patients' health is the priority, and whatever device used has benefits that outweigh the risk," says Ms Rojas, from Columbia University.

"I'm concerned about non-compliance, or poor lens hygiene and over-wear. These can lead to further complications like irritation, inflammation, infections or risks to eye health."

Like any contact lens, smart lenses will have to be used with care says Rebecca Rojas

With Mojo's lenses expected to be used for up to a year at a time, Mr Sinclair admits this is a concern.

But he points out that a smart lens means it can be programmed to detect whether it's being cleaned enough and even to alert users when it needs replacing.

The firm also plans to work with optometrists for prescription and monitoring.

"You don't just launch something like a smart contact lens and expect everyone's going to adopt it on day one," says Mr Sinclair.

"It's going to take some time, just like all new consumer products, but we think it's inevitable that all of our eye wear is eventually going to become smart."