The people making money from just surfing the internet

- Published

Most of what we look at on the internet is tracked

The details of what each of us look at online are an incredibly valuable resource.

This tracked data helps the likes of Google and Facebook earn billions and billions of dollars a year in advertising revenue, as they use the information to target adverts at us.

For example, if you are browsing online fashion retailers to potentially buy a new pair of jeans, you should very soon see adverts for the denim trousers appearing elsewhere on your computer screen. We have all seen this happen regarding whatever we were thinking of purchasing.

The level to which we are being tracked online in this way is somewhat unnerving. The average European has data about his or her internet usage shared 376 times a day, according to one recent study. For US surfers this almost doubles to 747.

But what if you could not only have more control over how much of your data is shared, but actually make money from it?

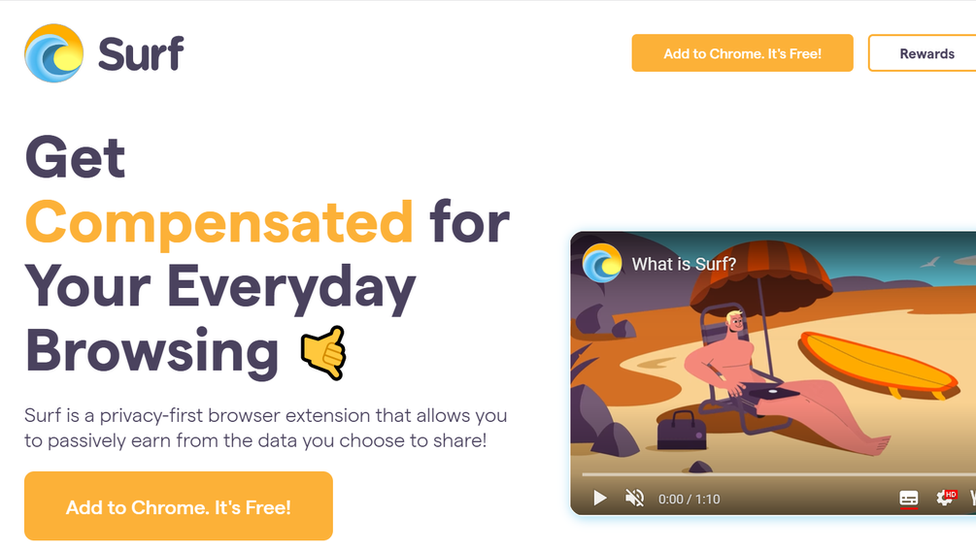

That is the promise is of a Canadian tech firm called Surf, which last year launched a browser extension of the same name. It rewards people for surfing the internet.

Surf wants to be "the frequent flyer rewards of internet browsing"

Still in its beta or limited release stage in the US and Canada, it works by bypassing the likes of Google, and instead sells your data directly to retail brands. In return Surf gives you points that can be saved up and then redeemed for shop gift cards and discounts.

Firms signed up so far include Foot Locker, The Body Shop, Crocs, and Dyson.

Surf points out that all the data is anonymous - your email addresses and telephone numbers are not shared, and you don't have to give your name when you sign up. It does however ask for your age, gender and approximate address, but these are not compulsory.

The idea is that brands can use the data that Surf provides to, for example, see what are the most popular websites among 18 to 24-year-old men in Los Angeles. Then can then target their adverts accordingly.

Surf hasn't released details of how much people can earn, but so far it says it has enabled users to collectively earn more than $1.2m (£960,000).

People can also use Surf to limit what data they share, such as blocking information about certain websites they visit.

One Surf user is Aminah Al-Noor, a student at York University in Toronto, Canada, who says she feels that the extension has given her "the control back" over her online data.

Aminah Al-Noor is able to earn points that can be redeemed for shopping vouchers from a number of retailers

"You can pick what you want to give Surf," adds the 21-year-old. "And other times I forget that I have it on, and a week later I will check, and my points just keep going up.

"All tech companies are going to collect our information, but the point is to make our experiences using the technology better, right," adds the 21-year-old.

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

Surf's co-founder and chief executive Swish Goswami says the firm wants to be "the frequent flyer rewards of internet browsing".

He adds: "From day one we have been clear with users on what we share and don't share, and we give them the ability to control their data as well.

"I think if you are upfront with people, and letting them know you are sharing data with brands, and you are doing it in an anonymised way - i.e. it cannot come back to them because we don't have their first or last name, then people are more comfortable to say 'yes' and share more with us."

Surf is part of a growing movement that some commentators have dubbed "responsible technology", part of which is to give people more control over their data.

Another tech firm in this space is fellow Canadian start-up Waverly, which allows people to compile their own news feeds rather than rely on Google News and Apple News' tracker and advertising-based algorithms.

With Waverly, you fill out the topics you are interested in, and its AI software finds articles it thinks you'd like to read. The Montreal-based firm is the brainchild of founder Philippe Beaudoin who was formerly a Google engineer.

Philippe Beaudoin wants people to pick what comes up in their new feeds

Users of the app can change their preferences regularly and send feedback on what articles are being recommended to them.

Mr Beaudoin says that users have to make a bit of effort, in that they have to tell the app the stuff they are interested in, but that in return they are freed from being "being trapped by advertisements".

"Responsible tech should empower users, but it also shouldn't shy from asking them to do some work on their behalf," he says.

"[In return] our AI reads thousands of articles a day, and places them in an index [for users]."

Rob Shavell's US firm Abine, makes two apps that enable the user to increase his or her privacy - Blur and Delete Me. The former ensures that your passwords and payment details cannot be tracked, while the later removes your personal information from search engines.

Mr Shavell says his view is that the surfing the internet should come with "privacy by design".

Carissa Veliz, an associate professor at Oxford University's Institute for Ethics in AI, says that tech firms need to be "incentivised to develop business models that do not depend on the exploitation of personal data".

Carissa Veliz wonders if regulators should take a closer look at the internet giants' algorithms

"It is worrisome that most of the algorithms that are ruling our lives are being produced by private companies without any kind of supervisions or guidance to make sure those algorithms are supportive of our public goods and values," she adds.

"I don't think transparency is a panacea, or even half of the solution, but policymakers in particular should have access to the algorithms."

Google points to its new "Privacy Sandbox" initiative, which has "the goal of introducing new, more private advertising solutions"., external

A Google spokesperson says: "That's why we're collaborating with regulators and the web community to create technologies, through the Privacy Sandbox, that will protect people's privacy online while helping keep online content and services free for all.

"Later this year, we'll launch My Ad Center, which expands our privacy controls to give people more direct control over the information used to show them ads."