Are we falling in love with robots?

- Published

Are these the droids you seek? Starship delivery robots waiting outside the Co-op in Milton Keynes

It's a fiercely hot afternoon in Milton Keynes and I'm chasing a small orange flag as it waggles just above a line of low garden walls. The flag is attached to a white robot with six wheels and I'm relieved to see that it's slowing down to a halt.

Cristiane Bonifacio has just extracted a large chocolate bar from the robot that has rolled up outside her home. Ms Bonifacio is in a hurry and has to dash back indoors for a work Zoom call, but she's got just enough time to express her affection for the robot delivery service that sends these machines scuttling along her local pavements.

"I love the robots. Sometimes you find one that's got stuck so you help it and it says 'thank you'."

The robot delivery service from Starship Technologies was launched in Milton Keynes four years ago and has been steadily expanding ever since, with further towns added just last month.

After decades of playing the villain in science fiction, robots are now part of life in many towns and people haven't just embraced them, they rush to assist them. What is going on?

"Technology can be adorable," says Amber Case

Amber Case is an Oregon-based specialist in human-robot interaction and the way technology changes everyday life. "In the movies robots are always a technology that's attacking us. But the delivery robots wait for us and we use them."

She thinks occasions when a robot hits an obstacle and requires help from a passer-by are a crucial part of the human-robot relationship. "Technology can be adorable if it needs our assistance. We like a robot that needs us a bit, and when we help the robot it creates a bond."

Curiously, Ms Case is critical of the Starship Technologies delivery robots that pepper the pavements of Milton Keynes.

They are battery-powered, summoned and opened by an app, equipped with sensors to detect pedestrians and armed with a speaker. This allows a remote human operator to address people observed through on-board video cameras.

Yet this arsenal of tech is not being applied correctly, she says. "I feel they are automating the wrong part of the journey. Humans are really good at negotiating terrain and finding a particular house. Is this just a fetish for automating things?"

Just like waiting for any other pedestrian...

Despite these reservations she concedes that "the Starship team have gone about it the right way, understanding how to make sure it's not scary, but cute. It seems they think more about the design than some robot makers and a well-designed robot is more likely to succeed."

The design element of the Starship robot chimes with the public. Victoria Butterworth recalls that the robots were one reason she moved to Milton Keynes.

"They caught my attention, they're so quirky and original."

She adds that "of course there were lots of other reasons to move here", but the robots came to play an important part in her life when her dachshund developed disc displacement and needed constant attention.

The robots allowed her to care for the dog without leaving her home to shop. "They were a real godsend when the dog was ill."

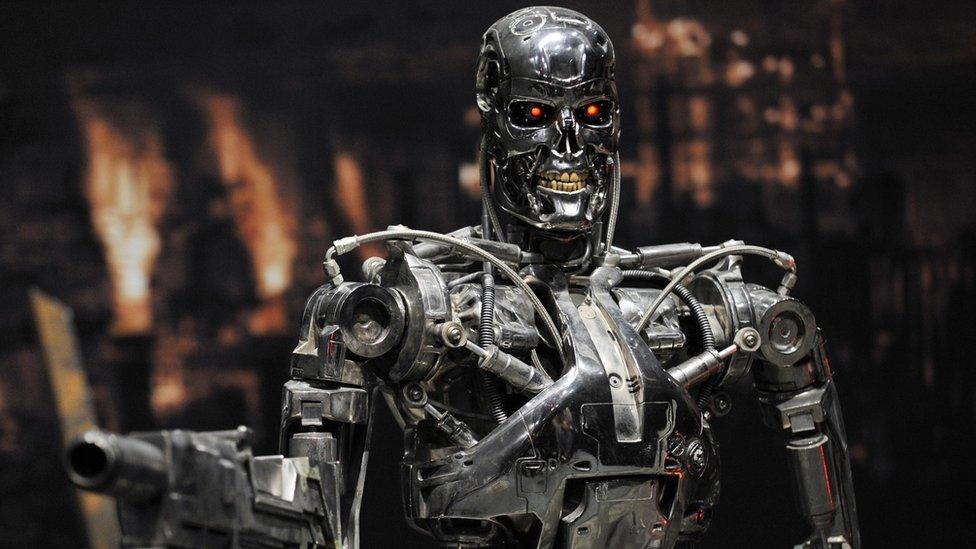

The Terminator robot is perhaps the best known of Hollywood's menacing machines

The human-robot bond emerging in Milton Keynes has banished the stereotype of a menacing robot, she says.

"When you see one you don't get that science-fiction emotion of 'Oh No! It's a robot!' It's more like a cute little character you see on the street. It makes your walk more colourful."

Andy Curtis, Starship's UK operations manager who is in charge of 180 robots in Milton Keynes, talks about each machine operating in a "bubble of awareness" that allows it to alert people to its presence and offer thanks if they assist it. "It's designed to be cute, not to be invasive."

This gentle demeanour is more than incidental. It pays off, says Mr Curtis. "People will jump in if a robot struggles on a difficult surface and it plays back a thank you message."

In Starship's native Estonia, pedestrians come to the rescue when robots encounter snow and ice on the streets of Tallinn, pulling them onto the pavement to be repaid with that popular voice of thanks.

Adam Rang, a businessman in Tallinn, confesses to being excited by the robots. But it's not an emotion his two-year-old son shares. "I point them out to him but he doesn't care. He's more interested in buses. It shows how normal they are to people born today, even though we've been waiting all our lives for robots like the ones promised in science fiction."

He adds that drivers in Tallinn are accustomed to halting at pedestrian crossings to let the robots pass over, even though Estonian traffic law does not afford them pedestrian rights.

He believes that part of our affection for the robots stems from disappointment with a promised future that didn't appear. "A lot of science fiction predictions didn't work out. But the robots give us the future we were promised."

Kids love fish and chips delivered by robot, says Johnny Pereira, co-owner of Moores Fish & Chips

Back in Milton Keynes the robots queue up outside Moores Fish & Chips on a Friday night. Co-owner Johnny Pereira explains why this mix of traditional and hi-tech has proved a hit with his regular customers and bedded in with the locals.

"Parents like to order robot-delivered fish and chips for the family, it's popular with kids. It's definitely increased business. But I can spot when customers sitting outside are new to Milton Keynes - they stare at the robots! People who live here are used to them."

At the local robot hub beside a mini-supermarket the little machines line up on the pavement, waiting for their next order.

Stephanie Daniels and her son, Noah, have dropped by and they too are impressed by robotic good manners. "I like it, they're very innovative, they have very good sensors. They're very cool and very weird at the same time. And they say 'Thank you!'"