Warning that post-lockdown jobs boom is ending

- Published

The UK's jobs market, which has been buoyant since the economy began to recover from the pandemic, might be starting to turn, experts have warned.

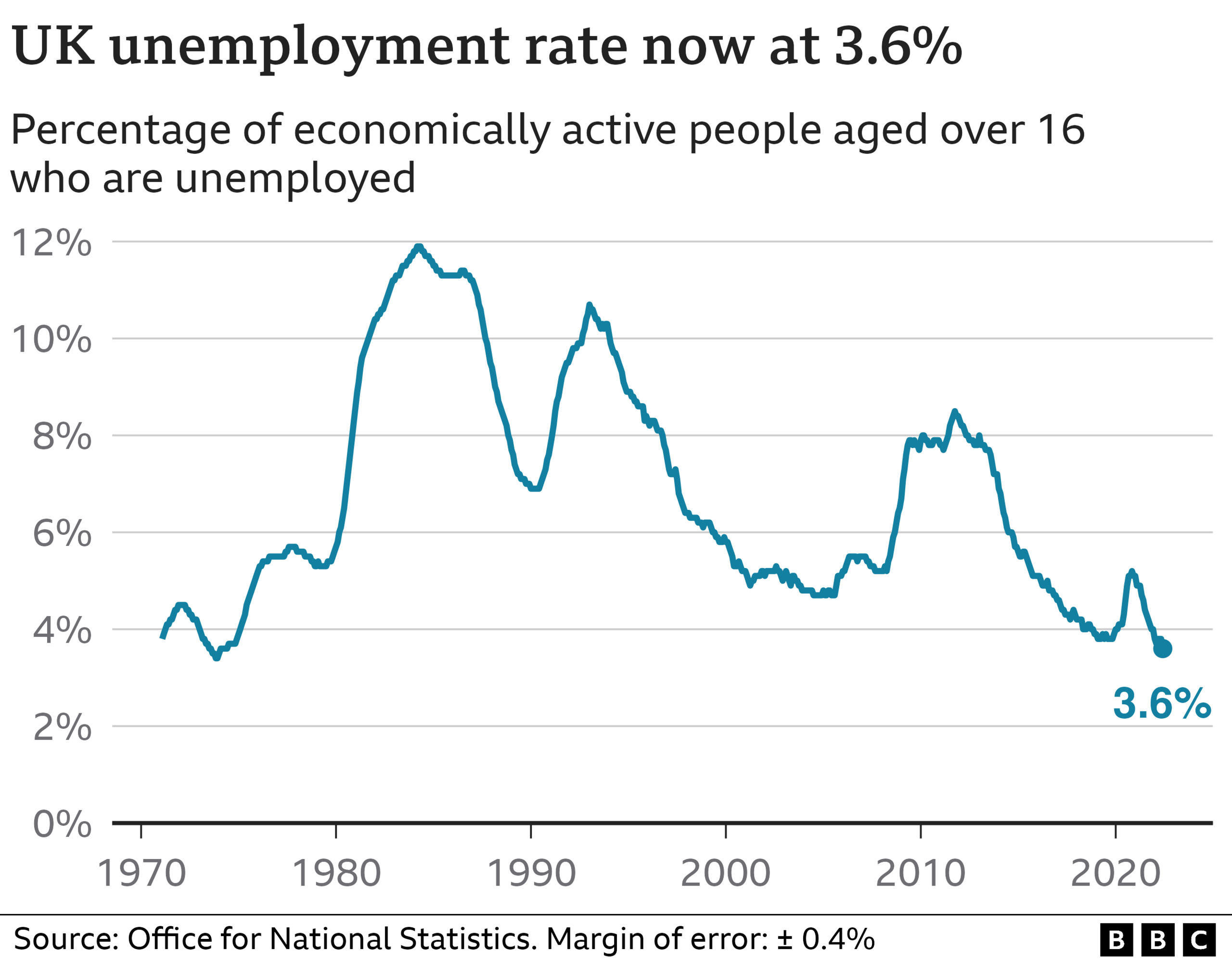

Although the unemployment rate fell to 3.6% in the three months to July - the lowest since 1974 - the employment rate and number of vacancies also fell.

Rises in regular pay are also failing to keep up with rising living costs.

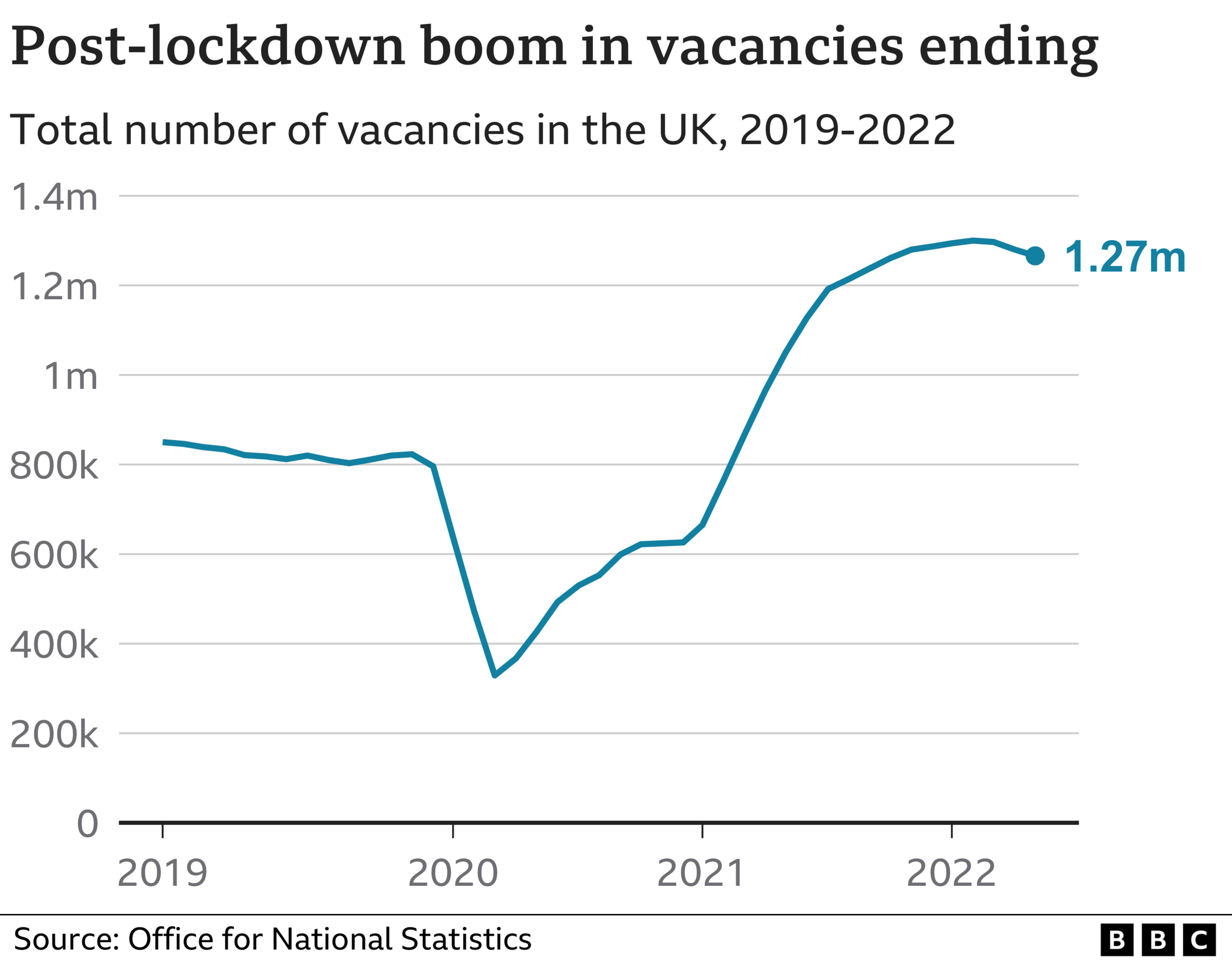

"The jobs boom that began six months after the pandemic is probably coming to an end now," said the boss of Reed.

Speaking to the BBC's Today programme, James Reed, who chairs the recruitment business, said: "There are still very large numbers of vacancies and people are still advertising a lot of jobs, and that's why we've seen unemployment continue to go down.

"The question is, what happens next? Will there be a jobs slump? That's a concern clearly but our data at the moment doesn't suggest that, because we've still got a large number of vacancies and a lot of employers are still struggling to recruit."

One reason for the fall in the unemployment rate is a rise in the number of people who are no longer looking for work, and so not counted in the figure. The inactivity rate rose to 21.7%, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said, external, the highest since 2017.

The squeeze on pay also remains, with rises in regular pay lagging behind inflation. When taking the rise in prices into account, the value of regular pay fell by 2.8%, the ONS said.

Inflation - a measure of price rises - remains at a 40-year high of 10.1% and the latest figure, due out on Wednesday, is forecast to be higher.

The continued gap between private and public sector pay growth was also visible from the ONS's figures.

Average regular pay growth for the private sector was 6% in May to July, compared with 2% for the public sector. According to the ONS, that is the largest ever difference between private and public sector, outside of the height of the pandemic period.

Despite the jobless rate falling to its lowest rate for 48 years, other measures suggested that the jobs market might be beginning to turn.

The number of job vacancies fell by the most in two years, down 34,000 between June and August, although the overall number of vacancies still remains historically high.

The employment rate also slipped to 75.4%, a small drop from the previous three-month period.

The EY Item Club said the fall in the unemployment rate masked some job market weakness.

"The decline in joblessness disguised what was only a modest 40,000 rise in employment, the smallest since January to March, with a rise in inactivity playing a bigger role in pushing unemployment down," said Martin Beck, chief economic adviser to the EY Item Club.

"Moreover, the single-month data showed the number in work in July falling on three months earlier to the greatest extent since January 2021. This suggests that the weak economy is starting to have an adverse effect on the jobs market."

While the headline jobs numbers remain strong, with the unemployment rate at its lowest in nearly half a century and long-term joblessness down, there are some signs of a turn here.

Firstly the lower unemployment rate is not really about a jobs boom, it is more reflective of fewer people actively looking for work. That in turn, in the very latest figures, arises out of record numbers of long-term sick. There could be an economic impact here from record NHS waiting lists.

So the latest jobs numbers remain the silver lining on some dark economic clouds. Other elements here reflect the wider cost of living pressures.

Real pay continues to fall sharply, especially for public sector workers. This is despite some high cash-terms pay growth. And despite a slowing economy, vacancies remain high. Labour shortages are in turn restraining businesses, and in particular could mean inflation remains higher for longer.

There is one unemployed person per vacancy, a record low, and the jobs are not being filled. But if the government wants to "go for growth" that will have to change.

Rob Sutton is facing challenges trying to recruit staff for his business.

Rob Sutton is founder of RKW, the UK's largest manufacturer, distributor and designer of small domestic appliances.

He employs 500 people in Stoke-on-Trent in the West Midlands and said his wage bill has gone up by more than £2.5m in the past two years.

"We are having to review our wage costs on a monthly basis because it is moving at that fast a speed," he said.

"It has been an absolute nightmare, where we are having to increase [wages] all the time so all our costs are going up and nothing is coming down at the moment.

His business is expanding and trying to recruit more staff, but it has been a challenge.

"We've probably got around 20 vacancies that we cannot fill," he says.

"We've had examples where recruitment agencies have come onto our car park where our employees are parked and they put letters on the windscreens saying 'we will give you £1,000 to come and join the company' to entice them away because there has been a massive shortage of order picking and warehouse operators.

"That's mainly because a lot of the European workers have gone home pre-Covid."

Labour shortages

Businesses have warned that the squeezed labour market is having a detrimental effect.

"With firms doing their best to keep afloat during a period of spiralling costs, they are also facing an extremely tight labour market which is further impacting their ability to invest and grow," said Jane Gratton from the British Chambers of Commerce.

"During a period of increasing inflation, and a stagnant economy, we cannot afford to let recruitment problems further dampen growth."

Tony Wilson, director at the Institute for Employment Studies, also warned that "firms simply can't find the workers to fill their jobs".

"This is holding back growth but also pushing up inflation, with pay growth in the private sector now running above 6% and contributing to even higher prices."

- Published16 August 2022

- Published16 November 2022