Will Liz Truss's economic plans make us richer?

- Published

With the death of Queen Elizabeth II, Liz Truss has faced an unprecedented challenge in her first month in the job.

Just as testing will be her pledge for a "bold plan to grow the economy".

On Friday, the Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, will outline a mini-Budget to deliver promises made by Ms Truss during her Tory leadership campaign to cut taxes.

The mini-Budget is expected to reverse a 1.25% rise in National Insurance and scrap a 6% increase in corporation tax at a cost of £30bn. A cut in the basic rate of income tax may, it's reported, be on the cards.

The announcement comes at a crucial time. Living standards are dropping at their fastest rate in decades and a recession may be imminent.

And on average, we have been underperforming against major economies over the past 15 years, while income inequality has widened.

All prime ministers promise to make us better off, but they differ in how they intend to do it.

All change?

Ms Truss's pitch echoes the small state mantra of those on the right of her party: "Cut taxes to reward hard work and boost business-led growth and investment."

The theory is that by allowing businesses and workers to retain more cash, they should spend and invest more which, in turn, should bring in more tax revenue. Cut red tape, and they have the freedom and incentive to do even more - what's termed supply-side reforms.

One of the chancellor's first moves was to sack the Treasury's top senior servant, Tom Scholar, who helped mastermind the UK's response to the 2008 financial crisis. It sent a stark message; Kwasi Kwarteng and his boss are plotting a new course, doing things differently.

But they'll face challenges.

Mr Kwarteng is said to want the UK economy to grow by 2.5% per year on average. That scale of growth has eluded many chancellors, whatever they've wished for, particularly since the financial crisis.

Cutting taxes marks a definitive break from the Conservative's austerity era. But many economists query if that will substantially revive growth. Analysts at Oxford Economics, using a model that mimics that of the Treasury, say that they would add just 0.1% to the level of output of GDP by 2025. History says tax cuts rarely pay for themselves.

They could, however, risk inflation - and so perhaps interest rates - staying higher for longer.

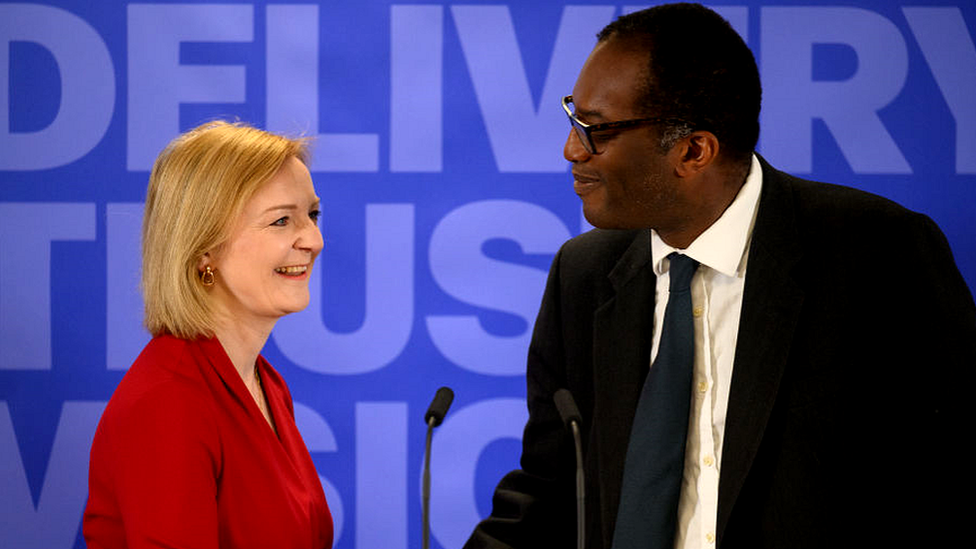

Kwasi Kwarteng supported Liz Truss's Tory leadership bid

Moreover, the Institute for Fiscal Studies calculates that those on the highest incomes will receive more than 200 times as much from these tax cuts as those on the lowest.

Ms Truss claims that it is fair and that everyone will ultimately benefit via higher growth - which is a move back to the "trickle-down" economics approach embraced by former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, and away from the redistributive approach of the past couple of decades.

"Trickle-down" may be the new "levelling-up" (a Boris Johnson-esque phrase absent so far) but it is questionable, on past experience, whether it will work.

And rising income inequality could pose electoral challenges. One think tank claims those on the lowest incomes in the UK are around a fifth worse off than their French counterparts.

Unravelling red tape

Slashing red tape, meanwhile, is a more familiar refrain but there are questions about what might be feasible or desirable.

Brexit allows the UK to diverge from the rules it had for financial services whilst in the European Union. But the Treasury Select Committee has warned against excessive deregulation. It claims that many rules imposed in the wake of the financial crisis worked to increase confidence in Britain's financial sector.

One such measure introduced during this period to deter excessive risk-taking was the cap on bankers' bonuses, a limit the chancellor is reported to be looking to scrap.

But what most economists do agree on is that underinvestment has been holding the UK back, making us a less efficient nation and restraining wage growth.

However, many say lowering taxes and red tape may not be a silver bullet.

Some, including Karen Ward, who was adviser to Philip Hammond when he was Chancellor, says the decline in investment became particularly marked from the time of the 2016 referendum as businesses waited to see how Brexit panned out.

The International Monetary Fund is among those saying that ending the current dispute with the EU over post-Brexit trading arrangements in Ireland could help revive investment by removing uncertainty.

But the prime minister has made no mention of the Northern Ireland Protocol and that continued stand-off with the EU could ultimately risk not just underinvestment but a trade war.

Even with a boost to investment, supply side reforms can take years to turbocharge growth.

Energy costs

Ms Truss's stance reflects a belief of allowing markets to work freely.

But ironically, it's the free workings of energy markets that's already prompted a change of plans as soon as she took office, a support package that signifies state intervention on what could be an unprecedented scale.

The plan to curb future spikes in energy bills will deflect much of the additional looming pressure on households and businesses - and prevent inflation accelerating much further.

But, the Bank of England suggests, it's too late to avoid a recession, although its length and depth could be less severe.

The package also risks adding even more to the government's debt than the furlough scheme. As it is, higher inflation already risks the interest payments on that debt exceeding £100bn next year.

Concerns about even higher debt has prompted the interest rate the government pays for new borrowing to hit a decade-high on financial markets.

This package doesn't mean Liz Truss has abandoned her smaller state vision. Instead - like Rishi Sunak when he became Chancellor at the start of the pandemic - circumstances prevailed, and she sees this energy crisis as an exception.

But she may yet face pressure to pump more money into the state. Schools and hospitals aren't immune to recent inflation. They'll need billions of pounds more simply to fulfil existing plans.

Ms Truss's strategy is indeed different - through design and necessity.

But will it pay off? The value of the pound has recently fallen to its lowest level against the dollar in almost four decades. Markets, already nervous about the UK's prospects, reckon her approach is a gamble.

Friday's tax cuts will boost many fortunes in the short run - but we won't know for some time if our longer-term prospects have improved.

Related topics

- Published15 September 2022