India gambles on building a leading drone industry

- Published

Uddesh Pratim Nath became a certified drone pilot after taking a five-day course

Newly qualified drone pilot Uddesh Pratim Nath is excited about the opportunities his new skills have opened up for him.

"Being certified has opened new avenues for me. I have been working with different industries like survey mapping, asset inspection, agriculture and many others," he says.

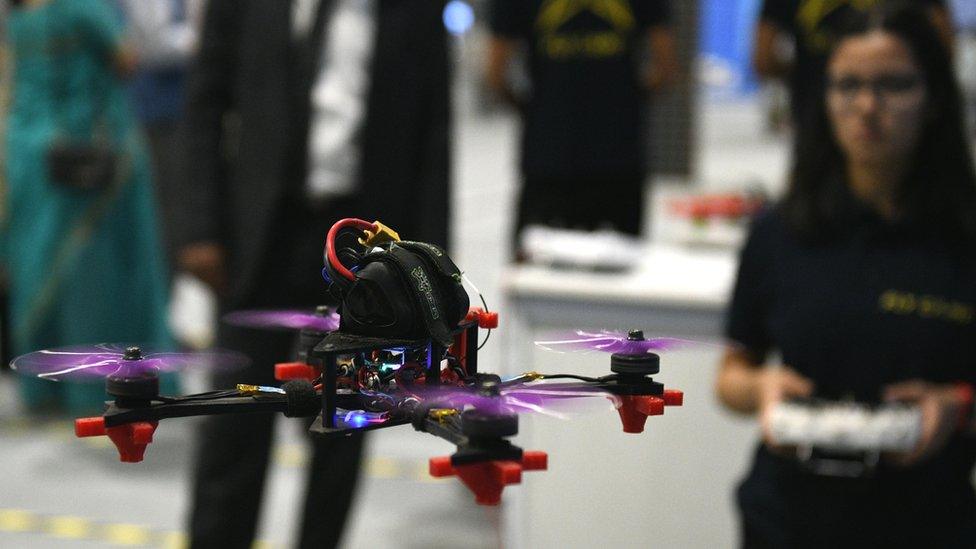

Drones come in all shapes and sizes. The smaller ones typically have three of four rotors and can carry something small like a camera. The biggest, usually used by the military, look more like aeroplanes and can carry substantial payloads.

Mr Nath, 23, had been designing drones, but decided that being certified to fly them would bring more job satisfaction and financial rewards.

A five-day course was enough to get him started, and he's now flight-testing drones that will be used for mapping.

Next he wants to master flying heavier and more complicated models.

The government wants India to become a leader in the drone industry

Mr Nath is reaping the benefits of a big push by the Indian government into the drone industry.

In February this year India banned the import of drones, except for those needed by the military or for research and development.

The government wants to develop a home-grown industry that can design and assemble drones and make the components that go into their manufacture.

"Drones can be significant creators of employment and economic growth due to their versatility, and ease of use, especially in India's remote areas," says Amber Dubey, former joint secretary at the Ministry of Civil Aviation.

"Given its traditional strengths in innovation, information technology, frugal engineering and its huge domestic demand, India has the potential of becoming a global drone hub by 2030," he tells the BBC.

Over the next three years Mr Dubey sees as much as 50bn rupees (£550m; $630m) invested in the sector.

Drone makers have "large order books", says Neel Mehta, co-founder of Asteria Aerospace

Neel Mehta is the co-founder of Asteria Aerospace, which has been building drones for 10 years. He welcomes the government's efforts to boost the sector.

It has allowed his company to expand beyond building drones for the defence sector and move into new areas.

"Drone companies now have a clear growth roadmap, large order books and promising future trajectory. In India, we now have drones being used in real-world, impactful large-scale applications, while being economically viable," says Mr Mehta.

Currently drones do all sorts of jobs in India. Police use them for monitoring the traffic and border security forces use them to search for smugglers and traffickers.

They are also increasingly common in the farming sector, where they are used to monitor the health of crops and spray them with fertiliser and pesticides.

However, despite the excitement and investment around India's drone industry, even those in the sector advise caution.

"India has set a goal of being a hub of drones by 2030, but I think we should be cautious because we at present don't not have an ecosystem and technology initiatives in place," says Rajiv Kumar Narang, from the Drone Federation of India.

Drones are used by India's police and security services

He says the industry needs a robust regulator that can oversee safety and help develop an air traffic control system for drones.

That will be particularly important as the aircraft become larger, says Mr Narang.

"Initiatives have to come from the government. A single entity or a nodal ministry has to take this forward if we want to reach a goal of being the hub by 2030," he says.

India also lacks the network of firms needed to make all the components that go into making a drone.

At the moment many parts, including batteries, motors and flight controllers are imported. But the government is confident an incentive scheme will help boost, external domestic firms.

"The components industry will take two to three years to build, since it traditionally works on low margin and high volumes," says Mr Dubey.

Drone pilots are in demand

Despite those reservations, firms are confident there will be demand for drones and people to fly them.

Chirag Shara is the chief executive of Drone Destination, which has trained more than 800 pilots and instructors since the rules on drone use were first relaxed in August 2021.

He estimates that India will need up to 500,000 certified pilots over the next five years.

"With 5G around the corner, the drone technology will have the platform to unleash its full potential, especially for long-range, high-endurance operations," he says.

Some companies are already using autonomous drones, external that use artificial intelligence (AI) to get to their destinations. Could that eliminate the need for drone pilots in the future?

It's not something that concerns newly certified pilot Uddesh Nath.

"Drones will always require a pilot or someone remotely controlling and monitoring them. Different drones require different handling and AI is not yet that advanced.

"Even if it learns to control itself, we cannot teach the drone to react in every situation," he says.