The little-known nut that may save at-risk rainforests

- Published

Are kenari nuts about to shoot up in popularity around the world?

Food scientist Marcello Giannuzzi asks an intriguing question.

"What do Italy and the Indonesian rainforests have in common?" he says. "Gelato," he quickly answers himself with a smile.

While few of us would make a connection between Italian ice cream, and Indonesia's tropical forests, Mr Giannuzzi is forging one thanks to a nut that is little-known outside of the Asian country, or even within.

The nut in question is called kenari, and it grows on the tree of the same name, which is native to northern and eastern islands and regions of Indonesia.

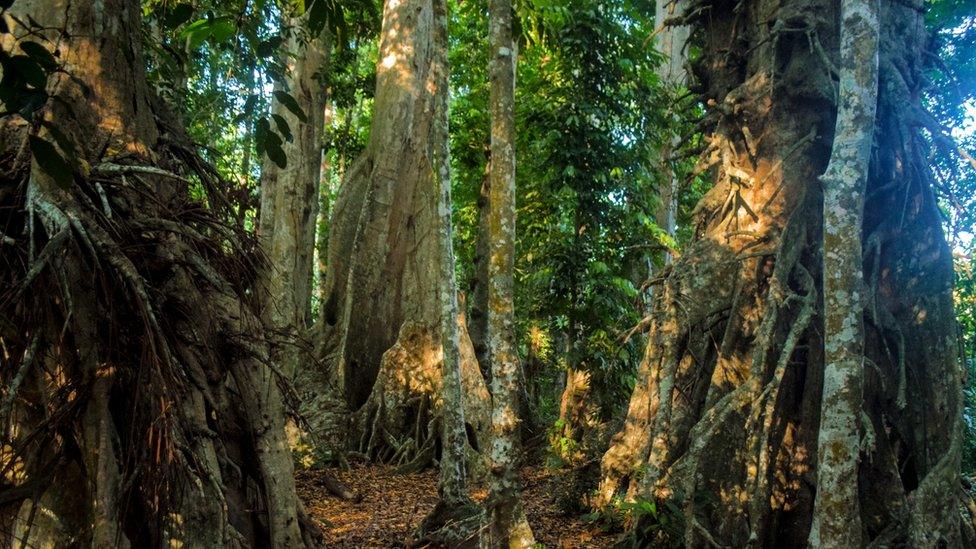

Harvested after they have fallen from wild trees, that can be more than 40 metres tall, the mild-tasting nuts have a buttery mouth feel, which Mr Giannuzzi says makes them an excellent dairy substitute.

Kenari trees are native to eastern and northern parts of Indonesia

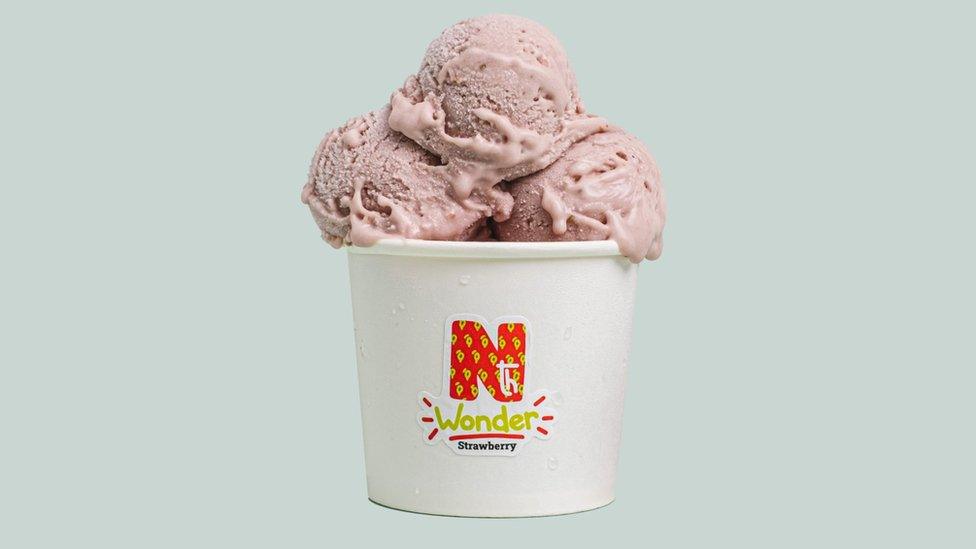

With that in mind he launched a kenari-based vegan ice cream brand earlier this year, called Nth Wonder.

Based in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta as well as Bali, after a successful launch of the ice cream in its home market, the firm now plans to export to Singapore, and then Europe and the US.

And in addition to the gelato, it is developing kenari-based cheese, yoghurt and milk substitutes.

"I believe the kenari is a hidden gem," says Mr Giannuzzi, who points to its sustainability. He says that as the nut grows on wild trees, it incentivizes the protection of rainforests rather than chopping them down to intensively farm oil palms.

And unlike almond farms in California, which require substantial irrigation,, external the kenari trees get all they need from rainfall.

To get to the nuts (left), they first have to be double shelled, and then a final skin needs to be removed

Mr Giannuzzi's firm sources its kenari from Alor Island, which is located some 1,600km (1,000 miles) due east of Bali, at the eastern end of the Lesser Sunda Islands.

Alor now produces around 16,000 tonnes of kenari per year, with the trees producing the nuts all year round. After being shelled, they are typically one inch or 2.5cm in length.

While you wouldn't want to try to lift 16,000 tonnes, to put it into context, California produced 1.18 million tonnes of almonds this year., external

Husband and wife business owners Felix Kusmanto and Debby Amalia King describe themselves as "pioneers of kenari".

Their Jakarta-based business Kawanasi has been selling the nuts in dried form under the brand name East Forest Kenari Nuts for the past six years in Indonesia. It now also exports to the US, Canada, Singapore, New Zealand and Japan, and will soon also ship to the UK and EU.

Felix Kusmanto and Debby Amalia King are evangelical about kenari trees and nuts

Like Nth Wonder it also sources its kenari from Alor Island.

"Before, locals saw kenari trees as having no economic value... other than chopping them down for timber," says Ms King. "We want to build a sustainable path for locals to walk into the rainforest to harvest kenari without ruining the jungle.

"We really want to educate the young people that this is a very good opportunity to go back to your village, and we also want to support education. These are very long-term goals for us."

However, she adds that she wants to see the harvesting of the nuts remain based on wild trees, and the planting of kenari farms, where new trees would start producing nuts in their seventh year.

"We don't want a mono-culture farm like almonds," says Ms King.

Their company is now producing 20 tonnes of dried kenari per month. The nuts are shelled on Alor, with final processing done in a factory near Jakarta. It sells them both unsalted and salted, and with additional flavours such as cacao and cinnamon, and spicy salted caramel.

East Forest Nuts' dried kenari are now exported to countries around the world

Kawanasi is also continuing to work with the Indonesian government to promote the nuts both inside the country and overseas, where it has participated in a number of international food fairs.

Prof Helen Wallace is one of the world's leading authorities on the kenari, and its sister trees and nuts, the pili and galip. These very similar trees are native to the Philippines and Papua New Guinea respectively.

Global Trade

A professor of agricultural ecology at Griffin University in Brisbane, she believes that the commercial development of wild kenari could bring great benefit not just to the environment, but to the indigenous people who call the Indonesian rainforest home.

"This nut has huge potential to benefit smallholder farmers and give them income from their rainforest trees," she says. "If we could commercialise more wild nuts from the rainforest like kenari it will help to diversify our food systems, prevent carbon loss and preserve our rainforests."

She adds she is hopeful that the creation of man-made kenari farms won't happen.

"At the moment this industry is helping to preserve the rainforest," she says. "That could change in the long term, so it's something that would have to be carefully monitored."

Nth Wonder is hoping that its ice cream is going to be a hit around the world

Back at Nth Wonder, in addition to its pre-packed ice cream it sells a kenari paste that can be shipped globally without the need for expensive refrigeration. This paste can then be turned into ice cream by other firms, simply by adding water, sugar and the required flavourings.

"As well as us selling ice cream direct to consumers, the technology is perfect for the business to business approach," says Mr Giannuzzi. "Its flexible enough to capture all the market opportunities."

He adds that he predicts that kenari products will prove to be a hit with environmentally-minded young people. "The kenari is really the perfect fit," he says.