Should countries try to do everything themselves?

- Published

Most experts think there is a strong case for countries to try to generate more of their own energy

Would it be better if a country simply produced everything it needed within its own borders rather than importing things from abroad? Would that make the country more secure, perhaps richer?

It sounds rather farfetched, but some of the world's most powerful political leaders have been making arguments that sound something like this in recent years.

"Our manufacturing future, economic future, solutions to the climate crisis - are all going to be made in America," declared US President Joe Biden, external earlier this year.

Similarly in China, the country's leader, Xi Jinping, has been advocating "zili gengsheng", which translates as "self-reliance".

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has also adopted a slogan of "Atma Nirbhar Bharat", external, or "self-reliant India".

In Europe, we hear similar language too, which seems to favour more national production over imports.

The European Union trade bloc is dashing to end its reliance on Russian gas in the wake of Vladimir Putin's invasion of Ukraine, which has sent European energy prices soaring to crippling levels and threatened blackouts this winter.

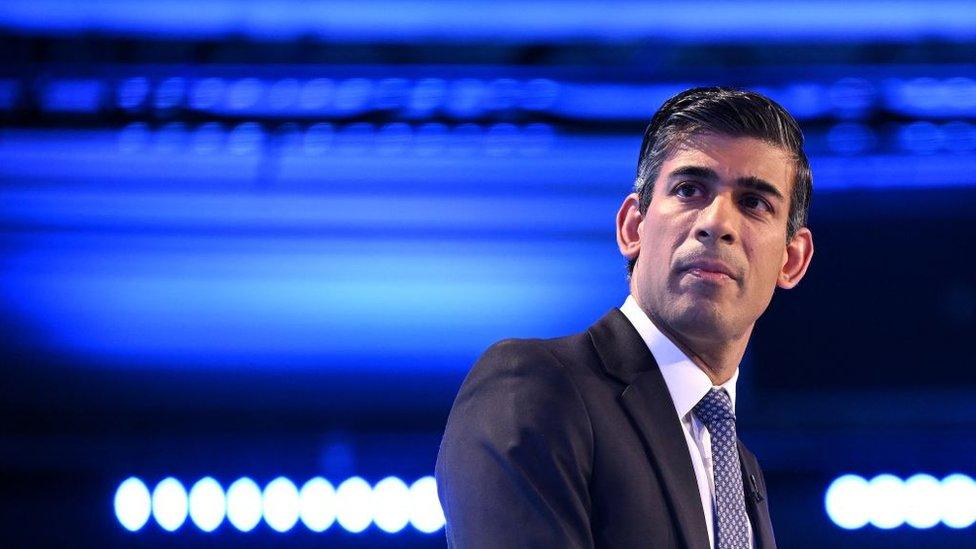

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has pledged to make the country "energy independent"

Both main political parties in the UK - the Conservatives and Labour - also say they will seek "energy independence".

The invasion of Ukraine - a major global supplier of wheat and other crops - has also led to spikes in international food prices, raising questions in many countries over the reliability of their food imports.

Even former staunch ideological advocates of free trade like the Conservative MP John Redwood now urges Britain to "grow and make more at home", external.

Some argue all this represents a shift away from the view of the past 40 years that global trade was good for our prosperity and towards a new goal, one of greater national economic self-reliance.

The ancient Greeks had a name for this kind of self-reliance: "autarky".

Some are even describing what has been happening in world politics and economics in recent years and months as an "autarkic turn".

But will these moves towards self-reliance deliver what their advocates promise in terms of security and prosperity?

When it comes to energy, most experts think there is actually a strong case for countries to try to do more at home. Not only for security reasons, but because modern domestically-generated renewable forms of power like wind and solar have negligible carbon emissions, unlike fossil fuels such as gas, oil and coal traded across borders.

In other words, this autarkic turn could help the planet to decarbonise and prevent destructive global warming this century.

As for food, experts like Tim Lang of City University have long argued that it would be better for our health and the environment if we all ate things that weren't produced such long distances away.

"The notion of autarky and food security are right up there at the top of policymaking at the moment," he says.

Another argument for greater self-reliance in food production is that it makes a country less vulnerable if those international supply chains are cut off due to weather, accidents or war.

Though, of course, consuming only the food that could be grown in a country like the UK would entail a big change in our diets.

Say goodbye to imports of things like bananas and pineapples. Experts say we would also have to eat far less meat because land for animal grazing would have to be given over to crops.

Say goodbye to that bunch of bananas

Ceyla Pazarbasioglu, director of strategy at the International Monetary Fund, agrees that countries should focus on the resilience of their energy and food supply chains.

But she warns of the damaging spillover impacts on less-developed nations of attempts at autarky.

"In the aftermath of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, we have seen around 30 countries imposing export restrictions," she notes.

"This has implications for many and especially the most vulnerable because their consumption of food is much greater in terms of their overall consumption."

Global Trade

But what about the case for autarky in things beyond food and energy?

Silicon microchips are used in virtually all forms of modern technology, from smartphones, to computers, to medical devices, to cars, to planes, to weapons systems.

And the majority of the world's most advanced chips are produced on the island of Taiwan, which is considered by China to be a part of its own territory, but whose independence the US effectively protects.

Both the US and China, fearful of the supply of these vital components being cut off from their economies in a potential conflict, have recently launched a major effort to produce more of these chips within their own borders.

Yet the chip production process is so complex and sophisticated and reliant on globe-spanning supply chains of raw materials and expertise that most experts think that even a country as wealthy as the United States will struggle to do it all at home.

So is this a new "age of autarky"? Or will political leaders come to realise that the global economy is simply too integrated, too interconnected, to be divided up into national blocks without inflicting intolerable pain on us all?

That could depend, firstly, on where they push their greater efforts at economic self-reliance, and, secondly, on just how far they push them.

Ben Chu's The New Age of Autarky? is available on BBC Sounds

Related topics

- Published7 November 2022

- Published27 October 2022