Train cancellations: 'Travelling to work can cost me more than I earn'

- Published

Jenna Blackburn holding her train ticket

Vet Jenna Blackburn's usual commute is Chester to Manchester, changing at Warrington, often on Northern.

But she regularly gets stuck in Warrington when trains are delayed or cancelled and has to get a taxi home.

She doesn't drive and on strike days there were no trains running. She said she took taxis to and from work which cost her more than £160.

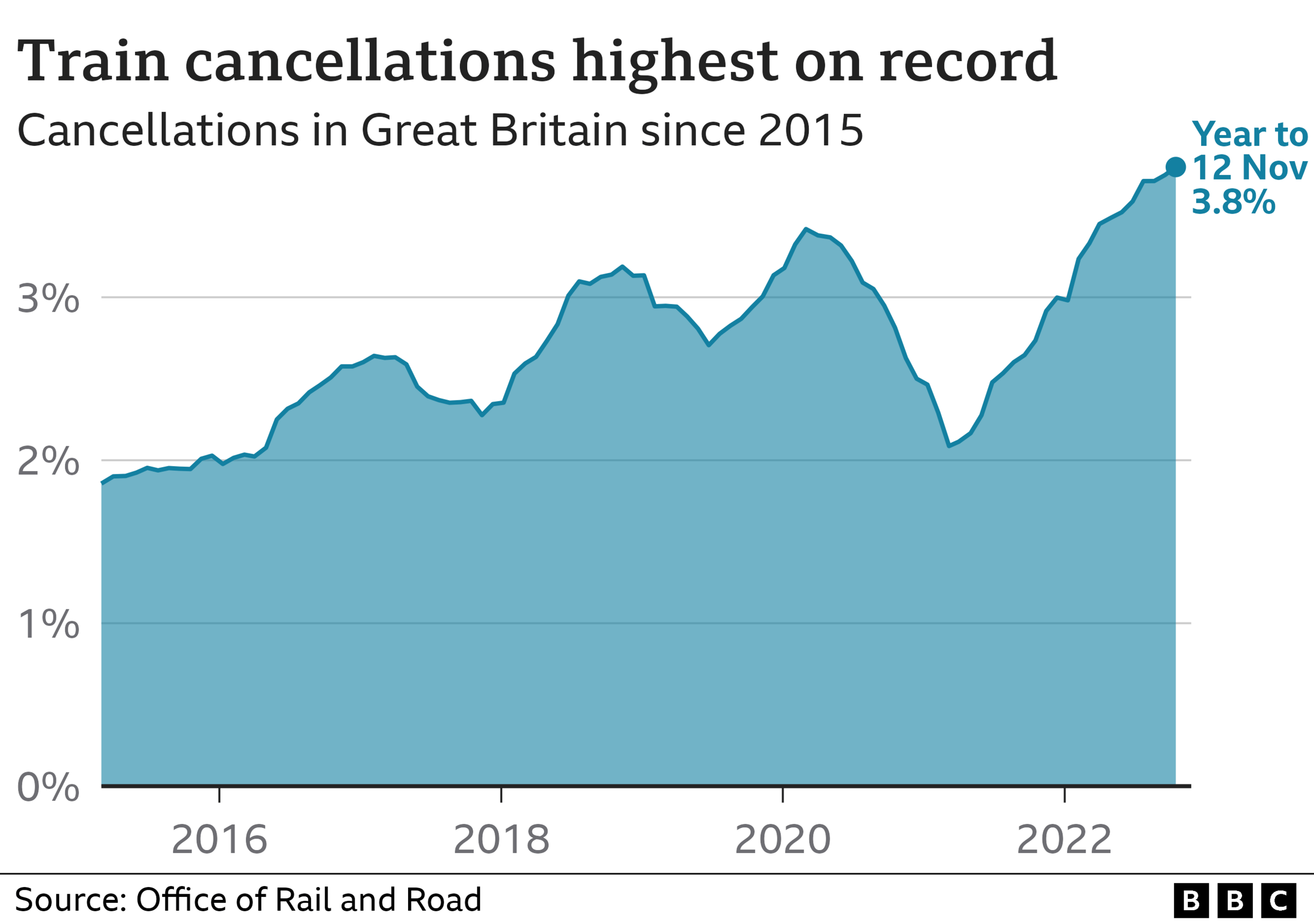

She is one of many facing disruption, with train cancellations at the highest level since records began in 2015.

Newly released data from the Office of Road and Rail shows 3.8% of trains in Great Britain have been cancelled in the year up to 12 November - or one in every 26.

"At least four times this year I've spent more on getting here and back than I have actually earnt that day," Ms Blackburn said.

"On a semi-regular basis I'm getting home at nine o'clock at night," she added. "Delay repay is about £6. It'll pay a quarter of your train ticket so it doesn't cover anything."

Ms Blackburn said a taxi home from Warrington to Chester usually costs between £30 and £40, depending on the time. But on strike days taxi prices are higher.

"Strikes are a nightmare because Chester station essentially just shuts down. This year I've had to spend £160 one day just to get here because it was a busy day for taxis so it was £160 here and back."

She added: "Over this year I've had to have hotels because I've not been able to get home on the last train because it's been cancelled and lots of taxis."

"Financially it's a lot," she said. "You're coming to work to make money and you can spend more than your day's wage to get home."

"Emotionally it's exhausting, to constantly have to look at the train times every single day. And hope I'm not going to be stranded," she said.

'Stress and expense'

When trains are running, Ms Blackburn said they are often crowded and strikes have added extra stress and expense.

The persistent disruption in recent months has prompted outcry from commuters, leisure travellers, politicians and business groups, particularly in the North of England.

The Transport Secretary Mark Harper is due to meet a group of mayors in the region on Wednesday to discuss the situation.

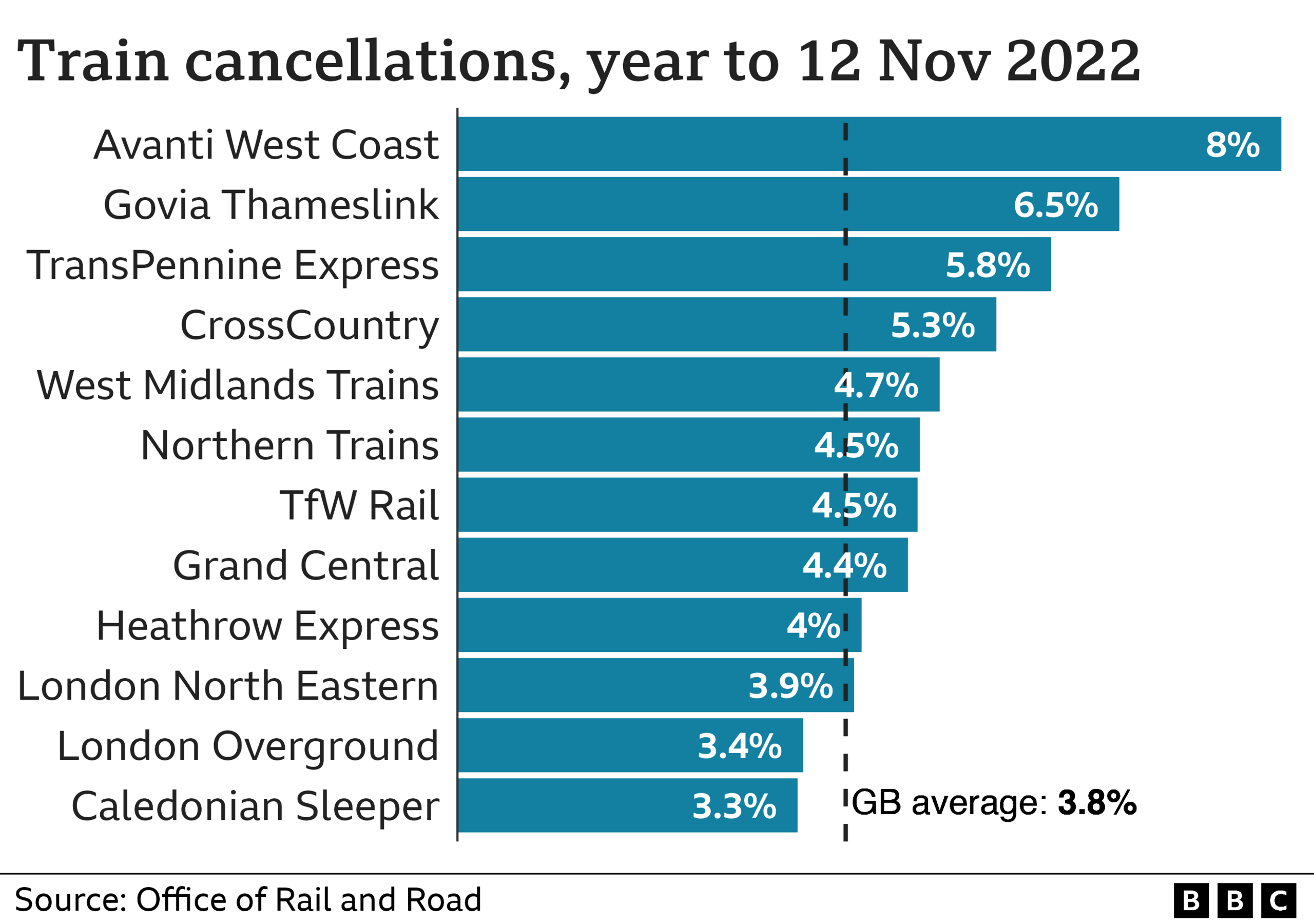

Cancellations vary across the country.

Avanti West Coast, which operates trains between London and Birmingham, Manchester, North Wales and Scotland, had the highest proportion of cancellations, at 8%.

Second highest was Govia Thameslink Railway - which runs Southern, Thameslink, Great Northern and Gatwick Express - at 6.5%.

Third was TransPennine Express, with 5.8% of trains cancelled.

These figures reflect on-the-day cancellations.

They won't include planned strike timetables, or the list of advance cancellations TransPennine Express releases on a daily basis.

In total, 520,853 services were scheduled across Great Britain between 16 October and 12 November, 15% lower than the same time in 2019.

Passenger numbers are currently only around 80% of pre-Covid levels - although they have been higher at some points recently.

Avanti has come in for particular criticism for severe disruption in July, and then slashing its timetable in August. It said the main reason was drivers suddenly stopped volunteering to work on their rest days.

In October, Avanti's contract was extended for only six months. The government said it must "drastically improve".

The train operator has apologised for the "enormous amount of frustration and inconvenience". It is still rebuilding services as more drivers are trained up, and says it's focused on restoring a full timetable in December.

TransPennine has also come under the spotlight for poor services, although it insists cancellation numbers have been reducing.

What's the problem?

Author and railway analyst Christian Wolmar said the railways were in the "worst state" he had seen in 25 years of writing about them.

Earlier this month I spoke to Steve Montgomery, the boss of First Rail; parent of both TransPennine Express and Avanti.

He apologised for performance not being good enough, and insisted the operators do employ enough train drivers; something their union Aslef disputes.

Mr Montgomery's explanation was that Covid directly caused a backlog of driver training, which can take up to 18 months, and staff sickness levels are high.

Added to this, reliance on drivers agreeing to work on days off - which has been common in the industry for decades - has left some operators exposed during a period of strained industrial relations.

Transpennine hasn't had a rest day working agreement in place with Aslef for nearly a year. It says this means less flexibility. But it says more drivers are, steadily, qualifying.

Avanti is aiming to restore a full timetable in mid December - without relying on overtime.

Angie Doll, chief operating officer of GTR, said performance over the past year had been affected by the impact of Covid, short-term sickness, severe weather and increasing trespass incidents.

She said the operator had a plan in place to make improvements, and was working with Network Rail to improve reliability. GTR also noted issues at other train companies could have a knock-on effect.

In a statement Tricia Williams, chief operating officer of Northern, apologised for disruption, putting it down to factors "including fully-trained driver availability and the on-going industrial relations issues with the trade unions".

These aren't the only operators with staff problems. On Sunday, train drivers in Aslef stopped working overtime at LNER, after a recent vote.

Infrastructure problems play a role too. ORR recently said Network Rail, which oversees tracks, power lines and signals, needed to do more to deliver better performance.

But Mr Wolmar said he believed there was more to the recent problems, with a "perfect storm" of factors.

"Some of it is actually downright poor management," he said. "And that opinion comes not just from me as a railway watcher but from a lot of the senior railway people I talk to."

During the Covid crisis, the government moved train companies onto emergency contracts.

Now, most train operators are paid on a performance-related fixed fee basis, and it is the government, that bears the financial risk - and holds the purse strings.

Mr Wolmar believes these contracts have resulted in less effort from managers to run a good service, and high sickness levels among staff who have gone over two years without a pay rise, are "really an expression of employee dissatisfaction".

The Rail Delivery Group (RDG), which represents train companies, said: "We totally reject any suggestion that the replacement of franchises with contracts during the pandemic is adversely affecting performance."

It added that while it was true that the Department for Transport now pays train operators a fee to run train services, that payment was performance-related.

The RDG said the pandemic has had a long-term impact on services by reducing the number of drivers and other staff who could be trained as well as increasing staff absences.

It acknowledged that the national dispute involving three rail unions had caused severe disruption and on cancellations it said "the industry is working hard to cope with an unprecedented convergence of issues".

Meanwhile, the future of how the railway is run is now uncertain, after the creation of a new umbrella body called "Great British Railways", was delayed.

Train companies are preparing to introduce a new timetable on 11 December - although RMT strikes are planned in its first week. Passengers will be hoping this change ushers in more reliability.

Are you affected by issues covered in this story? Email: haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803, external

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Or fill out the form below

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

- Published21 November 2022