Private workers' pay growth outpaces public sector

- Published

- comments

The gap between wage growth in the public and private sector is near a record high, official figures show.

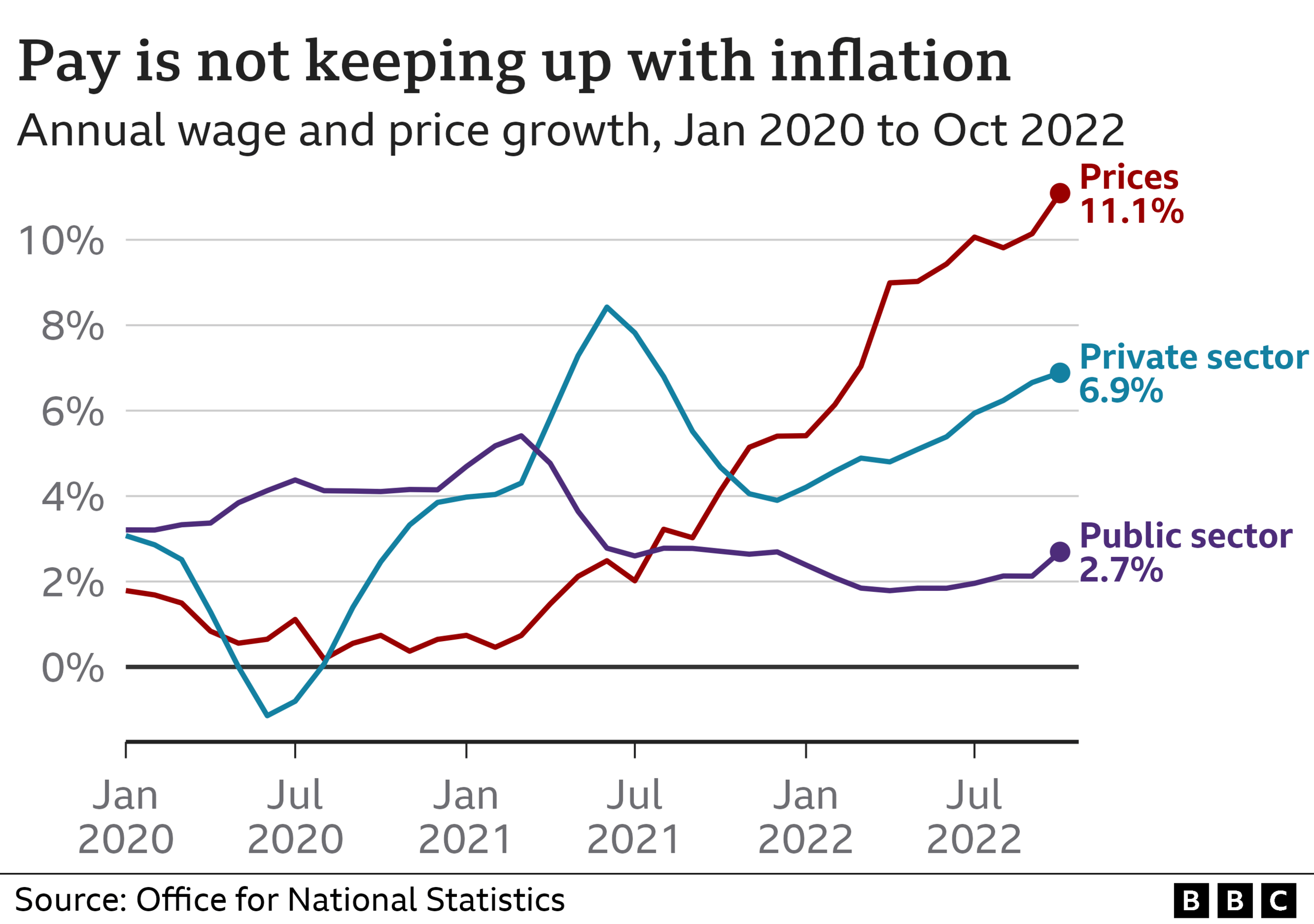

Workers in the private sector saw their average pay rise by 6.9% between August and October, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

That compares to wage growth of just 2.7% for public sector employees.

Thousands of workers are set to go on strike this week, including nurses who expect to stage their first-ever nationwide walkout on Thursday.

The 4.2% difference between pay growth in the public and private sectors is just below the 4.4% gap seen between July and September. The figures do not include distortions caused by the pandemic.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said that overall, regular pay grew by 6.1% in the three months to October. But taking rising prices into account, wages fell by 2.7%.

Workers across the public and private sectors have seen their wages fail to keep up with inflation, which measures how prices change over time. It currently stands at 11.1%, a 40-year high.

Strike action due to take place over pay and working conditions includes:

Thousands of workers across the rail industry started a fresh round of strikes on Tuesday, going into Wednesday. More walkouts are scheduled later this week.

Staff at Royal Mail who are members of the CWU will take strike action on Wednesday and Thursday. This will be followed by further walkouts on 23 December and Christmas Eve.

Nurses and ambulance workers are also planning industrial action later this month.

The ONS said that 417,000 working days were lost to strikes in October - the highest since November 2011.

Sam Beckett, head of economic statistics at the Office for National Statistics, said that the sectors that have been hardest hit by strike action are transport and storage as well as information and communications.

"That's been largely driven by the rail and mail strikes," she told the BBC's Today programme.

Ms Beckett said it was difficult at this stage to assess how industrial action has affected the wider economy.

"We haven't really seen the influence of that in our GDP statistics yet. It is too early to say how it will hit the economy more broadly," she said.

Overall, the unemployment rate rose to 3.7%. The number of job vacancies also fell, down 65,000 in September to November, which was the fifth consecutive fall for this measure.

Ms Beckett said the decline was a sign the jobs market "could be starting to soften a little" and an indication that some businesses were "were starting to pull some of their vacancies because they are reducing activity".

However, despite the fall, the ONS said job vacancies still remained close to historically high levels, with nearly 1.2 million roles available.

Perhaps the most interesting statistic in these job numbers - and the most telling for the future of industrial relations - is the enormous gap between public and private sector wage growth.

That will add tension to pay disputes where the government is the employer or sets the parameters for pay discussions.

Private companies can afford to slim down their ambitions and pay fewer people more - which is not an option in the NHS.

The numbers bear this out. Vacancies in hospitality are down 11%, whereas vacancies are almost unchanged in public administration and have gone up in education.

This elastic band must surely break at some point. More workers will leave the public sector, jeopardising key services or the government will have to buckle and agree to higher pay awards. It feels like something's got to give at some point.

There was also a decline in the number of people classed as economically inactive, which is those who are not in employment and have not sought work in the past few weeks. The most notable drop was among those aged between 50 and 64.

Jack Kennedy, UK economist at recruitment firm Indeed, said there was "evidence of some people returning to the labour force from retirement".

"That may be an early sign of cost-of-living pressures prompting some people to rethink their plans," he said.

But overall, inactivity remains more than 560,000 higher than pre-pandemic levels and continues to fuel recruitment challenges across a range of sectors, said Mr Kennedy.

Kai Clarke, who works at Purple Jay Nurseries' branch in Lambeth, said she was grateful for the 16% pay rise the firm had managed to provide for its workers - although it has quickly been absorbed.

Nursery worker Kai Clarke says she is grateful her pay has risen but so have her everyday bills

"I would say that I'm happy and I'm grateful but the excitement has worn off because I've noticed it is all going into the bills. Even simple things like juice, milk and butter have gone up."

While the manager of the nursery, Jarrod Ayling, told the BBC that putting wages up would have a big impact on his costs too, he said it was "needed because of the supply and demand situation" and the struggle to find recruits.

Additional reporting by Ramzan Karmali.

How are you affected by the strikes? Are you taking part in strike action? You can email: haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803, external

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Or fill out the form below

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at HaveYourSay@bbc.co.uk, external. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.

- Published11 December 2022