What happens now the US has hit the debt ceiling?

- Published

The risk that the US could hit its debt limit is the highest it has been in years

The US has hit its debt limit, with the Treasury Department now taking measures to prevent a potentially devastating default.

Reaching the debt ceiling means the government is not allowed to borrow any more money - unless Congress agrees to suspend or change the cap, which currently stands at almost $31.4tn (£25.4tn).

Typically that is what happens.

Since 1960, politicians have moved to raise, extend or revise the definition of the debt limit 78 times - including three just in the last six months.

But fresh tensions in Congress, where Republicans recently took control of the House of Representatives and are calling for spending cuts, have raised concerns that politicians will delay acting this time - potentially leading the US to intentionally default for the first time in its history.

So what would happen?

What will the US do now?

For most of us, the impact should be barely noticeable - at least in the first few months.

The US Treasury can manage the situation by taking measures to avoid actually breaching the limit. In the past, this has included steps such as suspending investments it is supposed to make into retirement and health benefit funds for federal employees - then retopping those funds at a later date.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told Congress in January that she would be taking those kinds of actions.

But even delays do have a real price.

The stand-off on the issue in 2011 prompted the S&P credit ratings agency to downgrade the country's rating - a first for the US.

Government analysts have estimated, external that delays that year caused the cost of borrowing for the US Treasury to increase by at least $1.3bn, as investors demanded higher rates due to the uncertainty.

Analysts are already expecting debate on the issue this year to make financial markets jumpy.

Then, economic catastrophe

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has estimated, external that special measures can buy time for the US until at least June, at which point the government will no longer be able to pay its bills.

That is the scenario many analysts see as a true economic catastrophe.

In the event, some say authorities would have to do as much as they can to avoid default. That would mean finding ways to make interest payments while other obligations go unpaid, such as defence contractor payments; Social Security cheques, received by retirees across the country; and salaries of government employees, including the military.

Even something as basic as weather forecasts could be affected, since so many rely on data from the government-funded National Weather Service.

A default could ruin the country's trustworthiness, roiling global financial markets, where US debt is heavily traded and has traditionally been viewed as low risk.

President Joe Biden has rejected calls to cut spending in exchange for lifting the debt limit

The dollar would weaken and borrowing costs would spike - at first for the government but ultimately for the broader public, in the form of higher interest rates for mortgages, credit card debt and other loans.

Getting to that point would be unprecedented, and cause widespread damage to consumer confidence and the economy, which is already in a precarious state.

"Failure to meet the government's obligations would cause irreparable harm to the US economy, the livelihoods of all Americans and global financial stability" Ms Yellen warned recently.

Why has this become an increasing problem?

The debt limit was first introduced in 1917, as a way to give the government flexibility to raise money during the First World War. In theory it gives Congress a way to check in on spending.

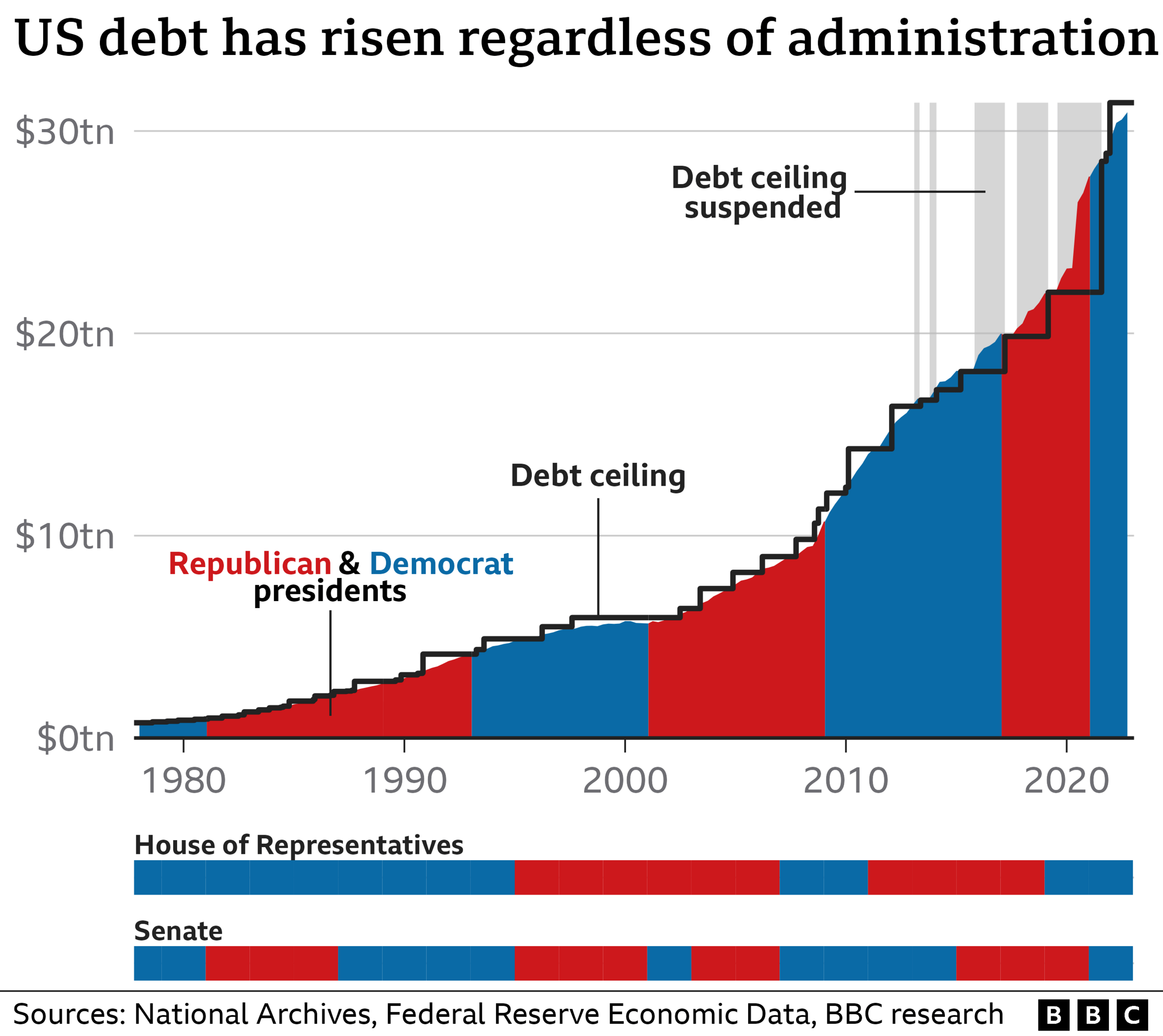

But fights over the ceiling have become increasingly fractious, as political polarisation increases and US debt has skyrocketed, roughly doubling in a decade.

That is due in part to major government spending during the financial crisis and the pandemic - but it is also a reflection of the fact that the country has consistently run a budget deficit - spent more than it raised - every year since 2001.

Now, the debt ceiling is a perennial political bargaining chip.

The 2011 fight over the debt limit was resolved when then-President Barack Obama agreed to spending cuts worth more than $900bn - and the debt limit was lifted by a similar amount.

Some Republicans are pushing for spending cuts again this time - a position that Democrats have rejected.

Related topics

- Published5 January 2023

- Published15 December 2021