'Our mortgage got so high we put off having a baby'

- Published

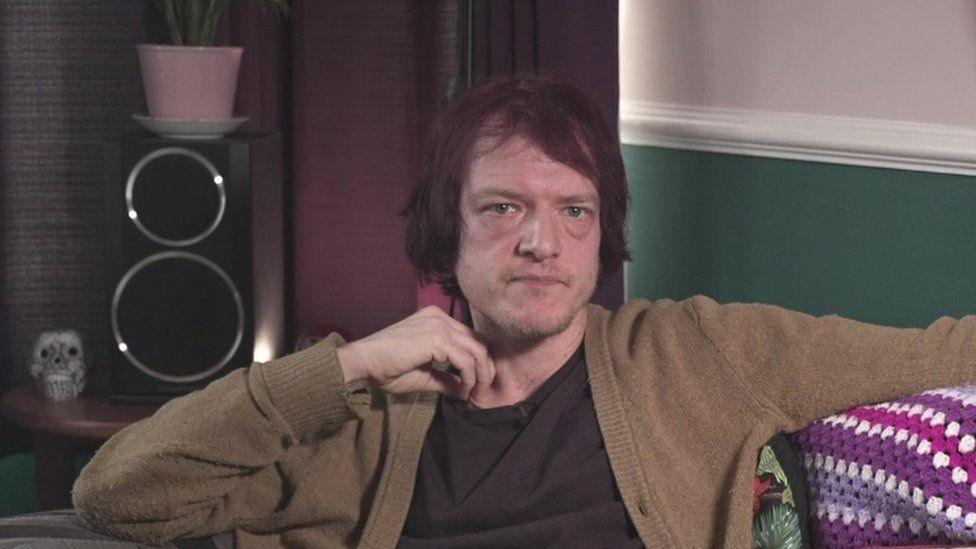

Alex Czok and her husband Tom Beech had hoped to start a family this year but when their mortgage went up by hundreds of pounds they put their plans on hold.

They are one of the four million UK households facing higher mortgage bills this year.

On Thursday, the Bank of England increased the UK's main interest rate to 4% - its highest in almost 15 years.

But mortgage payments aren't counted in the main cost of living figure that drives pay and benefit rises.

Ms Czok and Mr Beech, of Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire, were keen to get a move on with starting a family after the pandemic delayed their wedding plans.

They had done the budgeting for kids. They could make ends meet during a baby's first year with money set aside for her maternity leave or childcare later on. But that all changed.

"Because of the mortgage going up by £300, the money I was thinking of putting aside for the child, it would eat up most of that, so I will have to wait until we get a better mortgage deal," the 26-year-old said.

The average monthly mortgage bill will go up from £750 to £1,000, the Bank of England said in December.

The couple's repayments are going up by a bit more than that average rise of £250.

It's more than double the rise in energy bills that they had to suck up last year. Ms Czok says starting a family is going to have to wait.

Alex Czok and Tom Beech had already delayed their wedding due to the pandemic

The pay bump she got with a new job as an admin assistant for the council doesn't come close to the double hit of inflation and rising interest rates.

And it is a double hit: two different cost of living crises.

The official inflation number that drives discussions of the cost of living doesn't take account of mortgage interest costs.

But that number determines how much benefits will rise and it sets the tone for salary negotiations between employers and unions.

So the difference matters. Unions like Unison, which represents many council workers, say that "inflation statistics are of vital importance to our members".

Why doesn't inflation include mortgage payments?

The main measure of inflation - the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) looks at the prices of things we buy and use up: like food, fuel or holidays using internationally agreed rules.

It's designed for officials working out what to do with interest rates or for comparing the UK to other countries.

But it's not exactly the same as the cost of living.

You don't use up your house if you own it. Eventually you'll sell it, maybe at a profit. So the rules don't count house prices.

They also don't count the interest paid for things you buy with your credit card - only the original price is tracked.

But your cost of living does depend on interest payments. Especially the one in your mortgage.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) is developing new statistics, external designed to capture better the cost of living, including mortgages, for different types of households, like pensioners or families with children.

A bigger hit than food or fuel

Unison argues for a different measure of inflation that does take account of mortgage rates.

Inflation rose from 5% to more than 10% in the last year: a jump of more than five percentage points.

Adding mortgage rates in might push it up by about another two percentage points in a year like this with rapidly rising interest rates. It would push inflation down in a year with falling interest rates.

But if we want to target help to households with different needs, then our price statistics should be "specifically designed" to measure those different needs, argues Jill Leyland, an inflation expert at the Royal Statistical Society.

Most households won't be hit directly by the huge repayments that Ms Czok and Mr Beech will face. For example, people who don't own or plan to own a home or who have already paid off their mortgage.

But those who are getting hit will be hit hard. It moves serious money worries back up to people we would have previously thought of as doing ok.

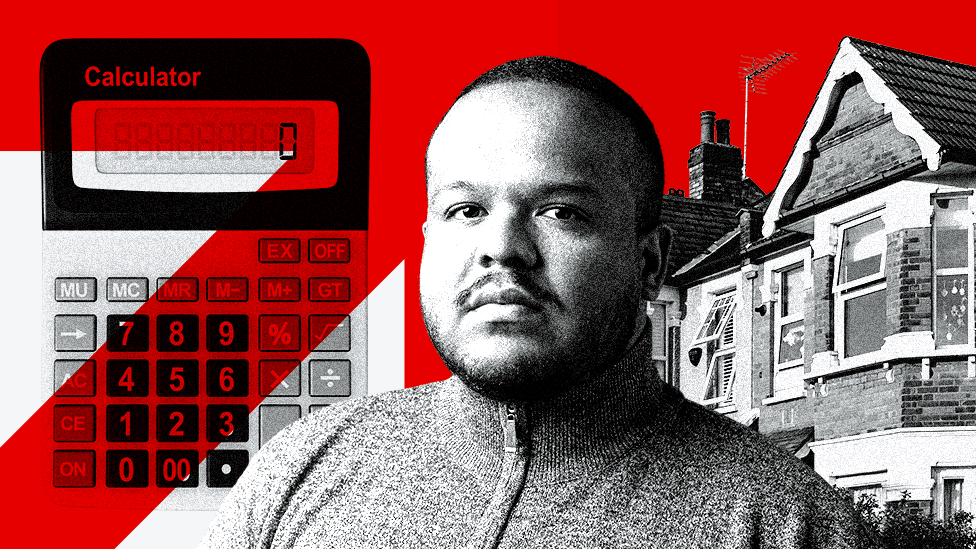

Stu Hennigan, for example, has a decent job as a senior librarian in Leeds, earning a salary that his 30-year-old self would have described as a "jackpot".

Stu Hennigan and his family spends almost a third of their income on their mortgage

But the rising cost of living means he's returned to the skint feelings he remembers from his younger, minimum wage days - using cards to spread unexpected costs like a car repair over a couple of months.

Half that hit came last year, with the food and fuel bills story familiar to everyone, just as the Hennigans' two kids started to reach the age of growth spurts and enormous appetites.

But the family's finances took another hit in November when their bank told them what their new mortgage payments would be.

They're now spending nearly a third of all their income on the mortgage.

But Ms Czok and Mr Hennigan still feel they're relatively lucky.

And Ms Czok and Mr Beech hope in a few years that time and money will be on their side when it comes to starting a family.

Additional reporting by Emma Pengelly and Bernadette McCague

Related topics

- Published5 January 2024