Credit Suisse: Bank rescue damages Switzerland's reputation for stability

- Published

So farewell to Credit Suisse. Founded in 1856, the bank has been a pillar of the Swiss financial sector ever since. Although buffeted by the financial crisis of 2008, Credit Suisse did manage to weather that storm without a government bailout, unlike its rival-turned-rescuer UBS.

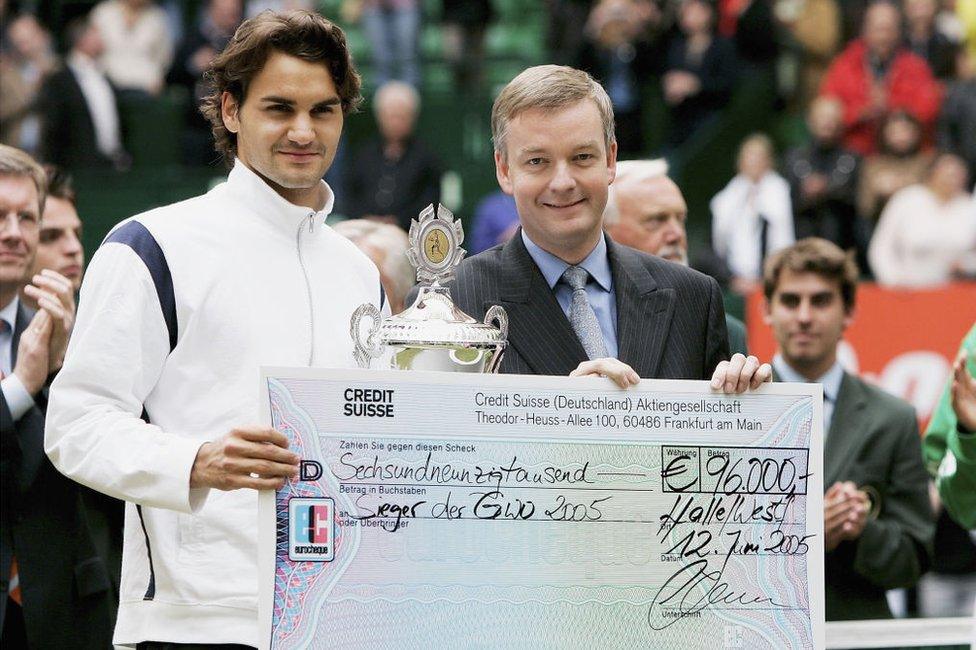

More recently, the marketing face of Credit Suisse has been Switzerland's tennis god Roger Federer. He smiles down from posters at Swiss airports, a symbol of strength, excellence, staying power and reliability.

But behind the glossy promotion were some big problems. Divisive management, costly exposure to finance company Greensill Capital, which collapsed in 2021, a seedy money laundering case, and waning customer confidence in the last few months, which saw billions being withdrawn from the bank.

All it took to turn those doubts into a stampede was an apparently off the cuff remark from the Saudi National Bank, which owns almost 10% of Credit Suisse, suggesting it would not be increasing its investment.

Credit Suisse's shares went into free fall, and even a statement of confidence from the Swiss National Bank, and an offer of $50bn (£41bn) in financial support, couldn't stabilise the situation.

Asleep at the wheel?

How could this have happened?

After the financial crisis 15 years ago Switzerland introduced strict so-called "too big to fail" laws for its biggest banks. Never again, went the thinking, should the Swiss taxpayer have to bail out a Swiss bank, as happened with UBS.

But Credit Suisse is a "too big to fail" bank. In theory, it had the capital to prevent this week's catastrophe.

Also in theory Swiss financial regulators and the Swiss National Bank keep an eye on those systemically important banks and can intervene before disaster strikes.

It was odd, last week, to see the rest of the world reacting with real concern as Credit Suisse shares tumbled, and to hear, at first, nothing from Switzerland.

Roger Federer went from winning prize money sponsored by Credit Suisse, to being its marketing figurehead

Even the Swiss media seemed not to notice the headlines over at the Financial Times, and seemed more interested in the continued debate over how much support neutral Switzerland should be offering to Ukraine.

By the time people did notice, such damage had been done that Credit Suisse was beyond saving. The fallout had begun to threaten not just Switzerland's entire financial sector, but Europe's.

As the government met in emergency session to try to find a solution, you could almost smell the panic in Bern.

Announcing the bank takeover, Swiss President Alain Berset said "an uncontrolled collapse of Credit Suisse would lead to incalculable consequences for the country and the international financial system".

It's hard to avoid the conclusion, some Swiss are now saying, that the very people who should have acted to prevent Credit Suisse's meltdown were asleep at the wheel.

Switzerland's reputation damaged

That lack of attention is going to be very costly. UBS's takeover, for the paltry sum of $3bn (£2.5bn), besides being an utter humiliation for Credit Suisse, is likely to leave its shareholders a good bit poorer.

There will also be job losses, perhaps in the thousands. There are Credit Suisse and UBS branches in just about every Swiss town. Once the takeover is complete, there will be little point in UBS keeping them all open.

But perhaps the most costly damage of all could be to Switzerland's reputation as a safe place to invest.

Despite the scandals over the years related to the secret bank accounts of dictators (including Ferdinand Marcos from the Philippines, Congolese dictator Mobutu Sese Seko and many more), or the money laundering for drug lords and tax evaders, Swiss banks hung on to that reputation symbolised by Roger Federer: strong, and reliable.

But now? A system that allows a 167-year-old bank to go belly up, in the space of a few days, at the cost of many jobs and massive losses in share value?

That could cause huge reputational damage. The Swiss banking sector, Switzerland's financial regulators, and its government, all say the takeover is the best solution.

In the end, at the very last minute, it was the only solution. In the coming days, there will be some tough questions to answer.

Related topics

- Published20 March 2023

- Published27 June 2022