Why is inflation higher in UK than other countries?

- Published

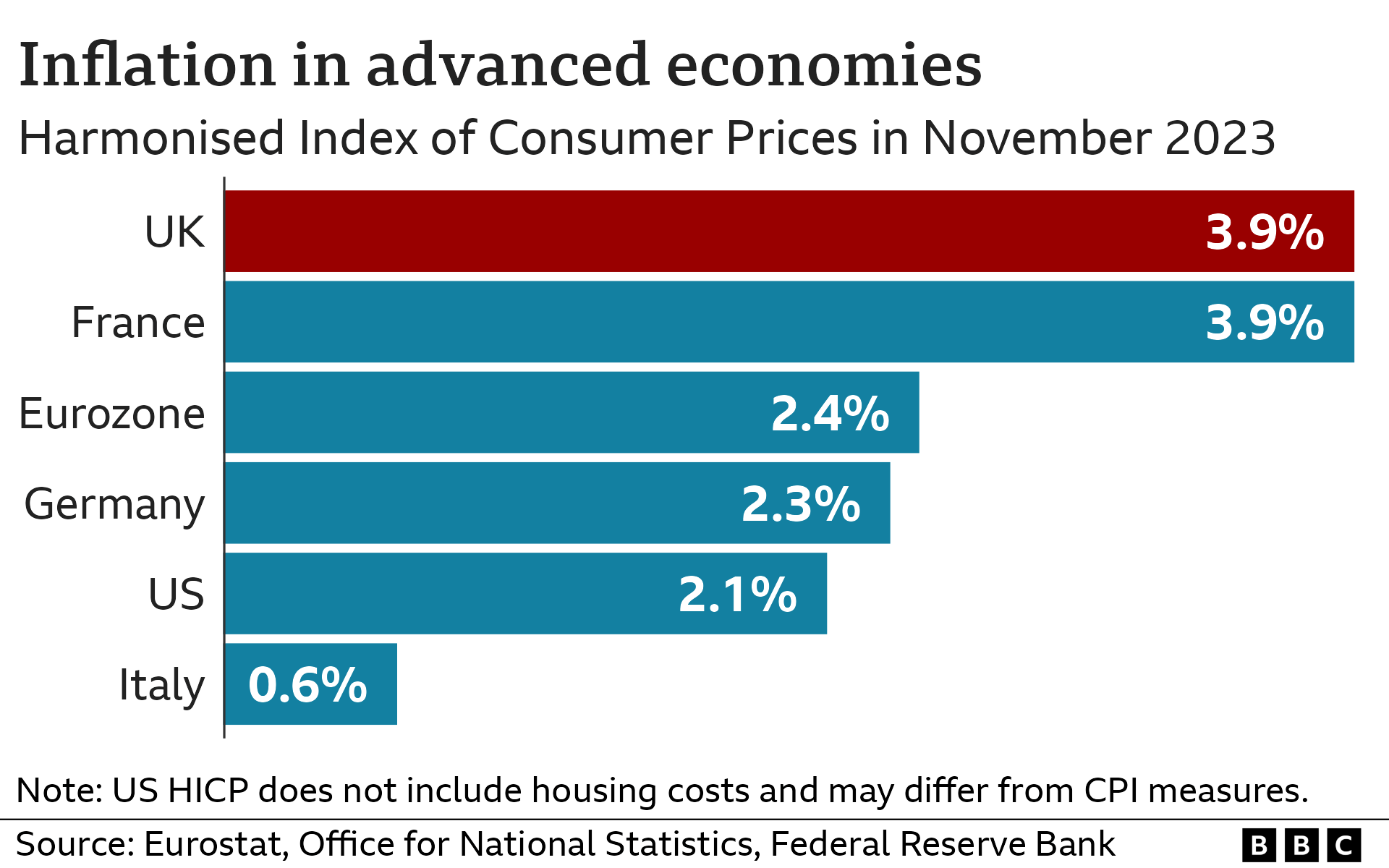

The UK's inflation rate has fallen to the lowest level in more than two years, but the cost of living is still rising faster here than in most of the world's advanced economies.

Prices rose by 3.9% in the year to November, in contrast to the US and the eurozone where inflation has eased to 2.1% and 2.4% respectively.

The UK has narrowed the gap on Germany and is now on par with France, but having been an outlier, many have asked: does the UK have its own inflation problem?

Overall inflation, which is the rate prices rise at, has been falling across the world, but it's taken longer to subside in the UK due to several factors.

Stubborn food price inflation has been one of the main issues eating away at household budgets in the past year.

It hit a 45-year high in November 2022 and while it has since fallen, it has been slower to come down than in countries such as Germany, Italy and the US.

Latest official figures show UK food inflation was 9.2% in November, compared with 7.9% in France, and 6.1% in both Italy and Germany. US food prices rose by only 1.6% compared with the same month last year.

It is partly because the UK has to import a lot more of its food than other European countries, says Grant Fitzner, chief economist at the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

"Import prices have gone up a lot more than domestic food, that's one reason why food prices have been so consistently high [in the UK]," he says. "If you compare headline inflation rates with most European countries we are a little bit higher, but if you look at food prices, they are more significantly higher."

Danni Hewson, head of financial analysis at investment firm AJ Bell, agrees. "The UK imports around 50% of its food which means adding additional transportation costs to the mix and on top of that costs associated with Brexit red tape for anything coming from the EU," she says.

UK supermarkets also tend to agree longer-term contracts with suppliers and producers, says Mr Fitzner.

This has meant grocers have been stuck in contracts at higher prices, while European counterparts have been able to agree cheaper deals sooner. It has also led to shortages of some goods on UK shop shelves.

'More susceptible to energy price shocks'

The UK has not been alone in being hit by rising global energy prices, leading to higher bills for businesses and households. But analysts have said Britain is more exposed to price spikes, particularly when it comes to gas.

Jonathan Haskel, a member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee, which sets interest rates, has previously said that the UK is one of the "most susceptible" countries to energy price shocks because it is more reliant on gas to heat homes and keep lights on than other European countries.

He added that the UK imported most of its gas via pipelines from a handful of suppliers, whereas the US produced most of its own gas.

France meanwhile has slightly cheaper bills as it generates more power from nuclear plants.

Ms Hewson says the UK's energy price cap, which limits how much suppliers can charge households, "cushioned consumers" from the rapid increase in energy prices following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, but she also thinks it created "an artificial bubble".

"When prices came down the impact was felt almost immediately by other countries," she says, although the gap between the UK and Germany has since narrowed.

Worker shortages and wage rises

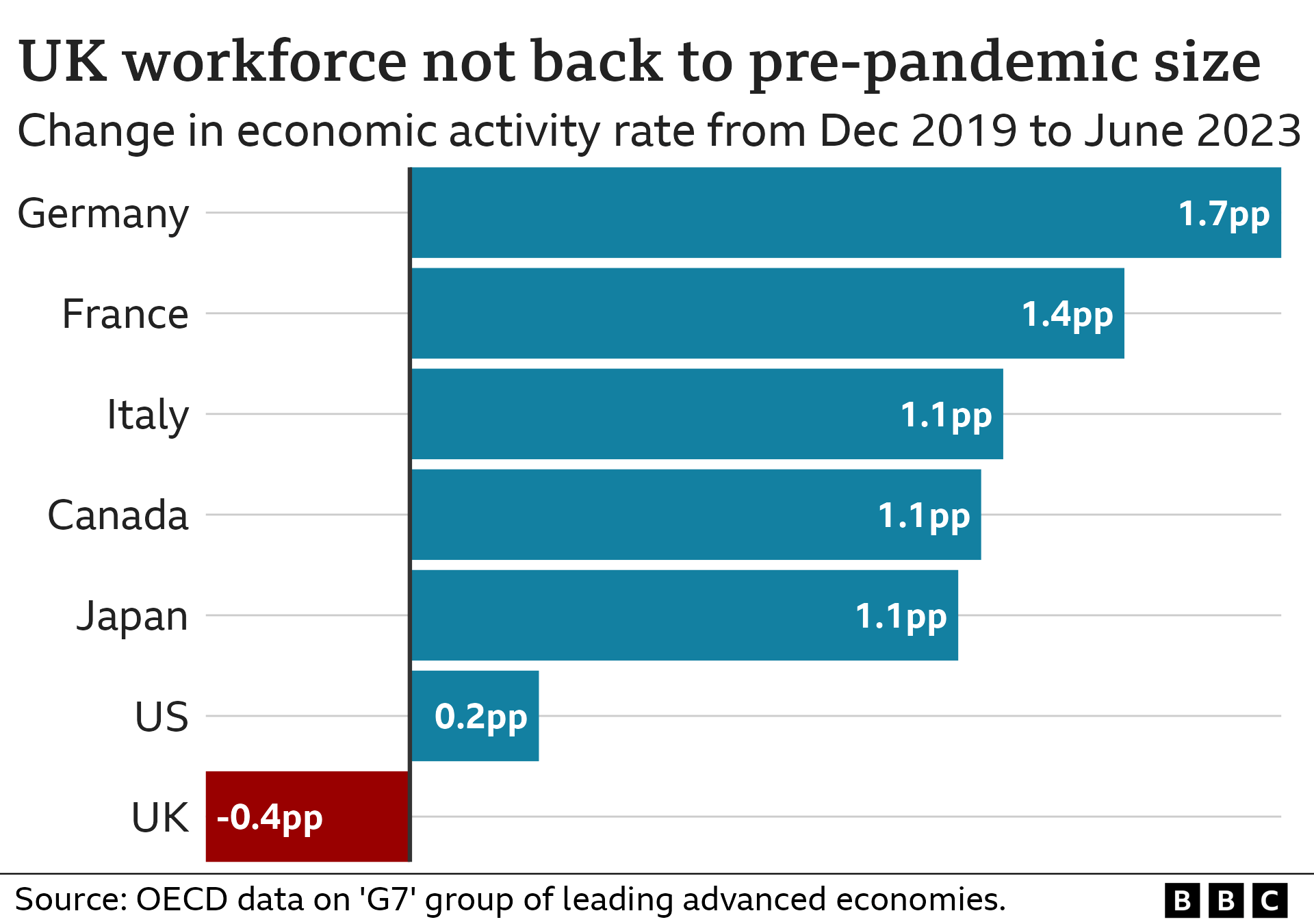

As well as baring the brunt of the energy price shock, the UK has also experienced the worst in post-pandemic worker shortages. This has pushed up wages, which some experts believe contributed to businesses putting up their prices.

During the pandemic all major countries saw their workforce shrink, but while most leading economies have since recovered, the UK still has about 400,000 more people not working than in December 2019.

Research has also suggested there are fewer workers due to Brexit, with sectors such as transport, hospitality and retail being particularly hard hit.

Other reasons include young people opting to study rather than work, older people retiring early, and more people being off work due to long-term sickness.

Because employers have had a smaller pool of talent to pick from, pay packets have risen to attract and retain staff, although wages recently starting outpacing prices which should ease the pressure on employers.

How are other countries tackling inflation?

Most economies choose to tackle rising prices by hiking interest rates. The idea is that by making borrowing more expensive, people will cut back on spending which cools demand, meaning prices do not rise as quickly.

But now that inflation rates have fallen, central banks appear to be changing tack.

The US central bank, the Federal Reserve, signalled last week it could start cutting interest rates next year if inflation continues to fall, with none of its rate-setting committee members believing they would have to raise rates further in 2024.

Both the Fed and the Bank of England have held interest rates in recent months, but the Bank's message has been more cautious - that rates will remain higher for longer and that it's too early to talk about cutting them.

"You could certainly argue that whilst the Bank of England was the first central bank of a major economy to pull the trigger, the US Fed pulled it harder and there is evidence that the big jumps so early in the cycle did help pour water on US inflation, dousing the flames more quickly," says Ms Hewson.

"But the economy in the UK and the US are vastly different and if the [Bank] had followed suit there is a real possibility that the UK could already be in the recession that had been forecast."