Why is technology not making us more productive?

- Published

We use technology in work more than ever before, but it isn't making us more productive

We are often told that we are in the midst of a technological revolution.

That business and the world of work continue to be transformed and improved by computers, the internet, the increased speed of communication, data processing, robotics, and now - artificial intelligence.

There is only one small problem with all this - none of it seems to show up in the economic data. If all this technology really is making us all work faster and better, there is precious little evidence.

Between 1974 and 2008 the UK's productivity - the amount of output you get per worker - grew, external at an annual rate of 2.3%. But between 2008 and 2020 the rate of productivity growth collapsed to around 0.5% per annum.

And in the first three months of this year, UK productivity was actually down 0.6% on a year earlier., external

It is a similar picture in most other Western nations. In the US, productivity growth, external between 1995 and 2005 was 3.1%, but it then fell to 1.4% from 2005 to 2019.

Computer processing has never been faster, but are we using it to do non-work things?

It feels like we are continuing to go through a huge period of innovation and technological advancement, but at the same time, productivity has slowed to a crawl. How can you explain this apparent paradox?

It might be that we are all just using the technology to avoid doing work. Such as endlessly messaging friends on Whatsapp, watching videos on YouTube, arguing angrily on Twitter, or simply mindlessly surfing the internet.

Or there might, of course, be bigger underlying factors.

Productivity is something economists look at very closely. And while it is a complicated issue, with the 2008 financial crisis and current high inflation having a negative impact, there are said to be two main explanations for why technology is not boosting productivity.

The first is that we are just not measuring the impact of technology properly. The second is that economic revolutions tend to be rather slow-burning affairs. And therefore, technological change is happening, but it just might be decades before we see the full benefits.

Dame Diane Coyle is the Bennett professor of public policy at the University of Cambridge, and a recognised expert on how we measure productivity.

"There is nothing that doesn't use digital now, but it is difficult to see what is going on because none of this is visible in the statistics. We just don't collect the data in ways that would help us understand what is happening."

Dame Diane Coyle argues that we aren't properly measuring the impact of technology

For example, a company that used to invest in its own computer servers and IT department might now outsource both to an overseas, cloud-based provider.

The firm doing the outsourcing gets the best software, updated all the time, and it is reliable and cheap.

But in terms of how we measure the size of the economy, this efficient move makes the company look smaller not larger. And it is no longer seen to be investing in that area of its IT infrastructure, which would have previously been measured as part of its economic growth.

Dame Diane has an example from the 19th Century's industrial revolution that illustrates how productivity can be missed from statistics.

"I have a wonderful 1885 yearbook of statistics for the UK, it is 120 pages long, of which almost all is about agriculture, and there are 12 pages on mines and railways and cotton mills," she says.

This was at the very height of the industrial revolution, the time of so-called "dark satanic mills", yet 90% of the data gathered was about an old, increasingly less important sector of the economy, and just 10% on what we now see as the one of the most important economic changes in world history.

"The way we see the economy is through the lens of how it used to be in the past, not how it is today," is how Dame Diane puts it.

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

The other argument is that the current technological revolution is happening, but just more slowly than we expect.

Nick Crafts is emeritus professor of economic history at the University of Sussex Business School. He points out that the huge sea changes in economic performance we tend to think of as having happened almost overnight, actually took decades, and the same may well be happening how.

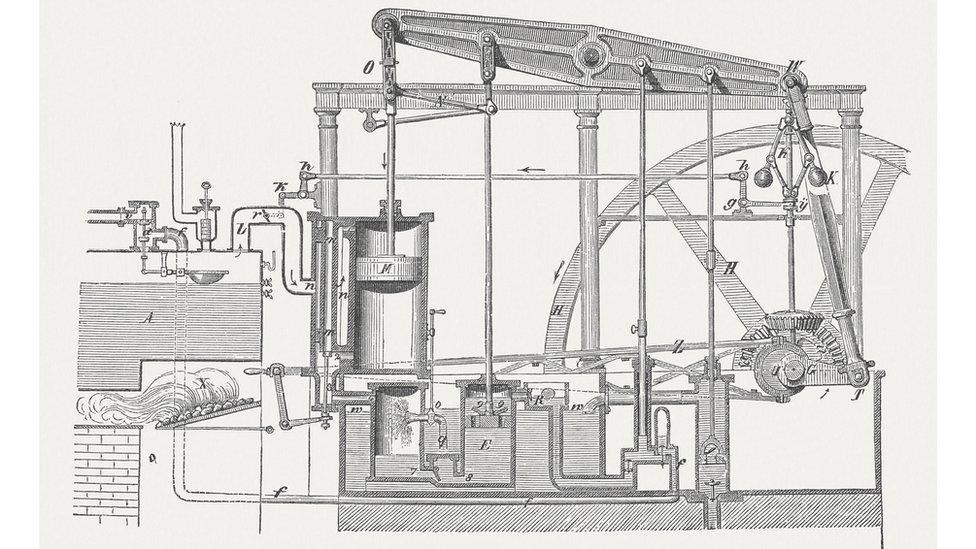

"James Watt's steam engine was patented in 1769," he says. "Yet the first serious commercial railway, the Liverpool to Manchester line only opened in 1830, and the core of the railway network was built by 1850. That was 80 years after the patent."

James Watt's first steam engine, pictured, was patented 61 years before the first commercial railway line

You can see the same pattern in the use of electricity. The time from Edison's first public use of the light bulb in 1879, to the electrification of whole countries and the replacement of steam power in manufacturing was at least 40 years.

In fact, we might be in a similar hiatus at the moment, something like when the world was between the peak of steam power and the full development of electricity.

But the country and the businesses that can make the best and fastest use of new technology are going to win the productivity race. This, as it was with steam and electricity, seems to come down not to the technology itself but to how well you can use it, adapt it, and exploit it - in short how skilled you are.

Dame Diane sees this happening already. "There is a lot of evidence now that whatever kind of company it is, there is a growing divergence between those that can use the technology well and those that can't.

"It seems to be that if you have highly-skilled people, you have a lot of data and you know how to use the sophisticated software, and you can change your processes, so that people can use the information, your productivity is going through the roof.

"But in the same sector of the economy there are other companies that just can't do that."

The technology is seemingly not the problem, and in some respects it is not the solution either. High productivity growth will come only to those that learn how to use it best.