Can narrowboat owners break up with fossil fuels?

- Published

London's canals are home to more than two thousand continuous cruisers

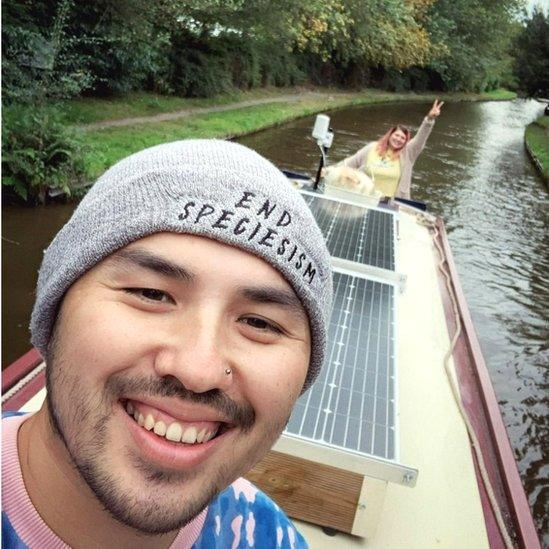

Narrowboat dwellers are some of the most energy-conscious people in London. And Amy Cross and Wes Arthur are no exception.

The couple have spent much of the summer navigating London's waterways on their slim 50-foot boat. As continuous cruisers, they're required to change their mooring locations every two weeks. Continuous cruisers can't count on prized permanent moorings with electricity points.

Miss Cross and Mr Arthur, who make chatty YouTube videos under the handle Boat Time, have three solar panels that provide most of their electricity in the summer, while still leaving enough space for them to picnic and grow plants on the boat's roof.

"We are just extremely aware of how much power we are using at any given moment," says Mr Arthur. They regularly check an app that indicates how much power is being drawn, and how much is left.

Like many permanent boaters, they've had to make sacrifices when it comes to energy-gobbling devices. Miss Cross has given up her hair straighteners, for instance.

Both are big computer gamers who also work in the gaming industry: she as a streamer on gaming platform Twitch, and he as a designer.

Miss Cross and Mr Arthur had to downscale their extensive six-monitor computing setup once they moved onto the boat in 2021.

Still, the power-hungry software Mr Arthur uses for game development on his laptop takes up most of their power on weekdays. Sometimes Miss Cross can only stream during the day, when there's abundant solar power.

Wes Arthur and Amy Cross have to closely monitor their electricity use

"Some games we can't play in the winter," Miss Cross says.

Like the Boat Time duo, it's common for narrowboaters to strategise which electrical devices are plugged in at the same time, so as not to overload the system. In winter, some boaters go without refrigerators or cool boxes.

In any season, devices like hairdryers and irons may be nearly impossible to run. For the fortunate few continuous cruisers who have miniature washing machines or air conditioners onboard, low-wattage models are the way to go.

Running a microwave for 10 minutes might take a narrowboat's solar panels three hours to redraw, according to Tim Davis of the company Onboard Solar.

Onboard Solar's systems are all designed to tilt 40 degrees in any direction. Being able to turn a panel toward the sun makes a big difference during times of the year when the sun is lower, Mr Davis says.

Even though the cost of solar power per watt has declined, prices of solar installation haven't come down hugely because the capacity has increased, says Mr Davis.

At Onboard Solar, £1,650 would cover full installation of what he calls a "decent" solar power system: three panels and 645 watts, as long as the client already has suitable batteries.

The main innovation he's seen in the narrowboat solar space is in the charge controller that acts as the bridge between the panel and the battery. Recent generations of charge controllers have allowed for higher voltage and better performance under different conditions of light and shade.

Working from a narrowboat can be a challenge

Solar technology that works in some shade is especially important for continuous cruisers in summer, who face tough decisions between cooling off their stiflingly hot boats under tree cover and mooring in full sun to maximise energy generation.

The Boat Time YouTubers have invested in, external a more efficient inverter, which turns the direct current generated by their solar panels into the alternating current used by the grid.

They also got new lithium batteries with much better storage, to replace their old lead-acid batteries.

While the battery upgrade wasn't cheap, and they had to buy a specific type with built-in heat pads so the batteries could be stored outside, Miss Cross says that "it was night and day, the difference that it made".

Mr Davis is hopeful for advancements in a different battery technology, lead-carbon batteries, which use gel rather than liquid. He says that the storage capacity is still limited, but lead-carbon batteries are easier to recycle than lithium ones.

Yet even with all this careful rationing of electricity as well as fuel, the narrowboat life isn't entirely clean.

Fully electric canal boats remain rare and expensive, and probably have to depend on backup diesel generators to power the engines. A fully electric boat could cost £200,000, whereas a more traditional boat might be £50,000.

And orders at one electric boatbuilder are backed up for almost three years, external.

Heat pumps for narrowboats are also uncommon.

On weekdays in winter, when their boat is stationary, the Boat Time YouTubers idle their diesel engine for about an hour a day to supply enough electricity.

"By the time I finish work it's dark, we can't really move anywhere," Mr Arthur explains. "So that's why we have to rely on idling the engine."

Engine idling is one of the activities that's restricted in an increasing number of eco-mooring zones in London.

The capital's councils are also considering extending smoke control areas to canals, to safeguard the health of boaters as well as other canal users.

These areas permit the burning of only smokeless fuel, or fuel in certain energy-efficient stoves. Traditional wood and coal, the main heating sources for many boaters, are not allowed.

Such limits have caused controversy among London's narrowboaters. A common argument is that life on a narrowboat is already more environmentally conscious than a land-based lifestyle.

Another is that the costs and space requirements of upgrading energy systems put this out of reach of the average narrowboater.

London is introducing eco-mooring zones with stricter emission rules

In one study of London boaters, external, 91% of respondents reported that they lacked the capacity to electrify their heating and energy in line with the requirements of eco-mooring zones.

At a local government level, financial support to upgrade energy systems would help. So would increasing the number of connections to mains electricity along towpaths.

For now, a number of residents who live near canals complain about narrowboats' stoves, engines and generators creating pollution that hangs about close to ground level, particularly affecting children.

A carpenter whose own narrowboat is moored in a clump of four boats says that when one of his neighbours idles her older diesel engine, the exhaust seeps right into his boat, nearly choking him.

The Boat Timers rely on a mix of heating sources. They don't want to get caught out without heat, especially since they share their boat with their pet rabbit and dog.

They sometimes use their diesel radiators, though a multi-fuel stove that burns wood and coal provides most of their heat.

"Obviously a lot of those aren't the greenest fuels, and we do sometimes get asked about that from people that hang around the canals and live in the houses," Mr Arthur comments.

"Our fuel is basically coming from similar sources, but because we are so aware, because we have to manage it to such an extent, I feel like we're very economical with it," he continues.

"We use a lot less than we ever would have done in the house."