The firms hoping to take psychedelic drugs mainstream

- Published

Josh Goldstein is in the first wave of licensed psilocybin facilitators in Oregon

This July in Bend, Oregon, Josh Goldstein facilitated one of the first magic mushroom sessions under the state's new regulatory framework for people to access their active ingredient - psilocybin.

Mr Goldstein's 71-year-old client was seeking help with his obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The man experienced his psychedelic trip at a licensed psilocybin service centre after eating a measured quality of the dried fungi. Mr Goldstein, a licensed psilocybin facilitator with Bendable Therapy, prepared him for what to expect ahead of time, and then guided him through his six-hour long experience.

At the follow-up integration session, the man described his experience to Mr Goldstein as "lifechanging". "He had a profound realisation, which he believes has subsequently significantly shifted his OCD," says Mr Goldstein.

Oregon voted by ballot to legalize psilocybin for use by adults in supervised settings in 2020, becoming the first state to enact such a measure (the drug is illegal in the US federally).

Colorado recently followed with a wider swathe of psychedelics, and other states seem poised to continue the trend.

The states' approaches are for non-medical use - the drugs do not have regulatory approval for therapeutic use, and are currently banned at the federal level.

But the promise they have shown in helping combat a variety of hard-to-treat mental health conditions has doubtless influenced Oregon's framework, and will likely drive much of the demand for the services there.

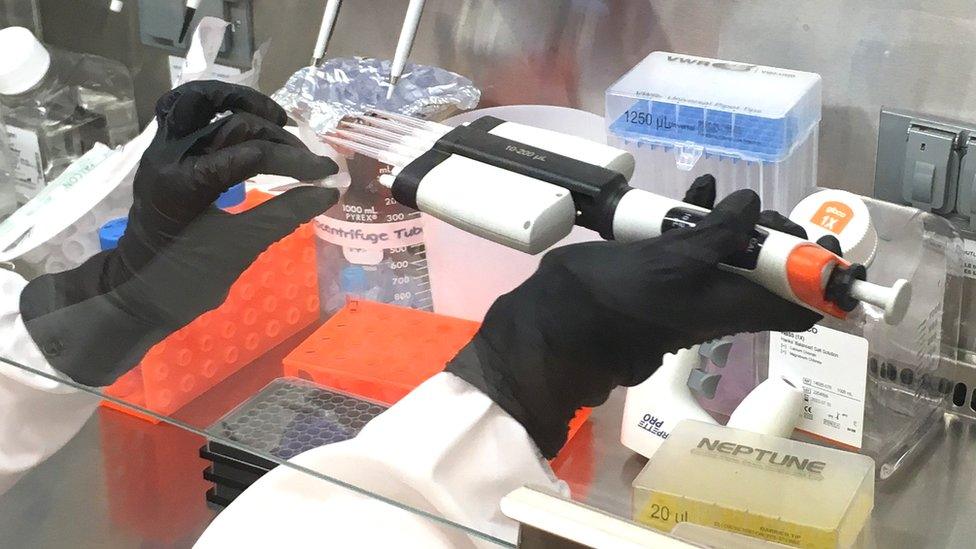

Psilocybin mushrooms ready for harvest

In therapeutic trials the standard approach is to give the drugs in supervised sessions augmented to a greater or lesser extent by therapy before, during and after.

If psychedelics are ever going to go mainstream they will have to be approved by regulators as prescription medicine, which, in addition to providing assurance they are safe and effective, in the US opens up the potential for health insurance coverage.

MDMA (ecstasy) and psilocybin assisted therapy for PTSD and treatment resistant depression, respectively, are furthest forward, with MDMA recently successfully showing efficacy in a phase 3 clinical trial, and a similar trial for synthetic psilocybin is currently in progress.

As well as clearing regulatory hurdles, it's likely the treatments themselves will have to change.

The six-hour treatment experienced by Mr Goldstein's client is likely to be too time-consuming for many patients.

So biotech firms are already working on next generation psychedelics, which aim to either shorten the trip time, or cut out the mystical, hallucinogenic part altogether.

"Shorter-acting psychedelics and non-hallucinogenic psychedelics have become popular among investors in the past couple of years," says Josh Hardman, an analyst at Psychedelic Alpha, which tracks the sector.

They remain a "hotspot" even of late, as investment in the psychedelic drug industry more broadly has been dipping. Mr Hardman estimates about a dozen or so companies have adopted it as a main or at least significant focus, and, while it is hard to estimate precisely, at least $500m (£400m) in investment has flowed in.

Start-ups are tweaking psychedelic compounds to speed-up treatment

Among those pursuing a shorter trip with a novel molecule similar biologically to psilocybin is Gilgamesh, a US start-up founded in 2019 (others include Canadian public companies Mindset Pharma and Bright Minds).

A shorter psychedelic experience could both entice more patients - not everyone is able to spend a day in a dosing clinic - and free up clinical space so more people can receive treatment, says Andrew Kruegel, the company's co-founder and chief scientific officer.

Gilgamesh has a compound, which is intended, with some psychotherapy, to treat depression and anxiety. It is currently in a phase 1 clinical trial (focussed on safety).

Like psilocybin, it targets serotonin receptors in the brain, which drives the hallucinogenic effects, but the length of the trip is reduced to about an hour.

Alternative approaches others are pursuing include starting with very short-acting psychedelics related to psilocybin, and modifying them chemically so things last longer. And, separately, changing the way psilocybin is delivered from orally to intravenously to give a shorter experience.

UK-based Small Pharma has a drug candidate that extends the trip length of DMT (the active ingredient in the hallucinogenic beverage Ayahuasca) from 20-30 minutes to about 45 minutes.

Beckley Psytech, also UK-based, is looking at the intravenous administration of psilocybin's biologically active metabolite, psilocin, which would bring down the length of the trip to about an hour and a half. Both have initiated phase 1 clinical trials.

Other firms are looking at losing the hallucinogenic component altogether, which, potentially, would open up psychedelics to being taken at home (as there's no longer a chance of a bad trip).

David Olson doubts whether the hallucinogenic experience is necessary for treatments

Among the start-ups taking a purely non-hallucinogenic tack include US-based Delix Therapeutics and Psilera, both also founded in 2019.

Delix's approach is to try and harness the anti-depressant like neuroplasticity effects of psychedelics - research shows they promote the growth of new neural connections which better allow the brain to rewire its circuitry - but leave behind the subjective, mystical experience.

Convincing people is hard, but there is "no definitive evidence" that the hallucinogen experience is the cause of psychedelics' therapeutic effects, says David Olson, the company's chief innovation officer and an associate professor of chemistry, biochemistry and molecular medicine at the University of California, Davis.

Prof Olson, co-founded Delix off the back of his laboratory's work there.

Tested in mice, Delix's leading molecule doesn't appear hallucinogenic. It is currently also in a phase 1 clinical trial that will tease out whether that's also true in people, says Prof Olson.

The company hasn't declared which mental illness will be its first target, but the advantages Prof Olson anticipates of non-hallucinogenic psychedelics over antidepressants is they would kick in much sooner, and could be taken less often (antidepressants take weeks to months to work and need to be taken daily).

Yet others are doubtful the same outcomes will be seen with shorter trips, or without the trip altogether - they believe that the subjective, mystical experience is important, and the longer the trip, the better.

Gül Dölen, an associate professor of neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University, studies how psychedelics work. Her research shows they open a window of time - a so called "critical period" - in the brain where it is more sensitive to the environment, and has an enhanced ability to learn and form lasting memories (psilocybin's critical period, for example, lasts two weeks). And the longer the trip, the longer the critical period.

The companies trying to shorten trip duration or remove the hallucinogenic component "are probably going to interfere with the therapeutic effect" says Prof Dölen, who also emphasises the importance of therapy after the trip for the learning opportunity it can provide.

Mr Goldstein, the psilocybin facilitator agrees. For him, the idea of either snuffing out or shortening the psychedelic experience is nothing short of repulsive.

"Coming into contact with yourself takes time and active participation," he says.

Help and support

If you're affected by any of the issues in this article you can find details of organisations who can help via the BBC Action Line.