The weird materials behind sustainable furniture

- Published

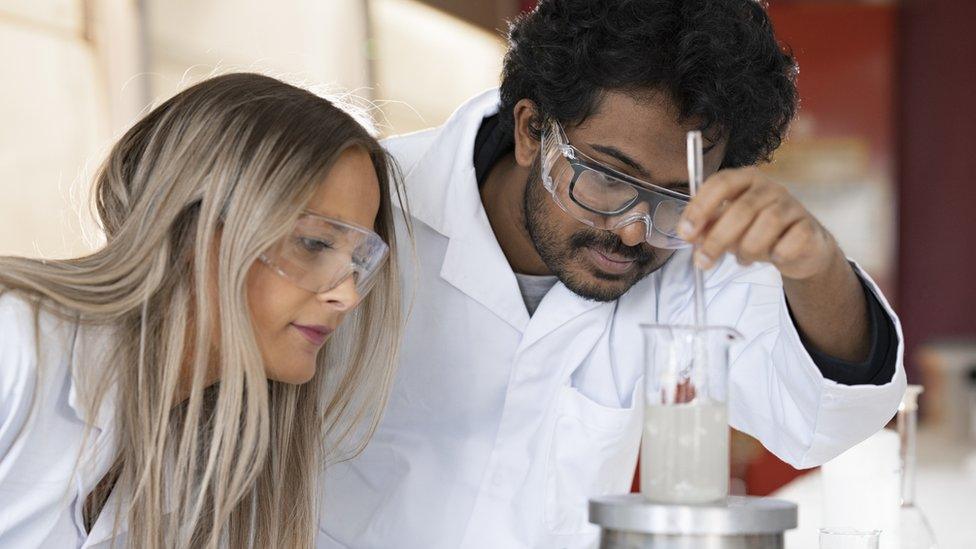

Celine Sandberg found that seaweed can be used to make foam for furniture

From crushed oyster shells to agricultural waste, Celine Sandberg has experimented with some wacky ingredients to make parts for furniture.

Her aim has been to cut the use of plastic polymers, known as polyurethane, in furniture making. That meant finding a more environmentally-friendly material to fill pillows, sofas and chair cushions.

To start with, the founder of Oslo-based Agoprene and her colleagues experimented with using oyster shells. The shells were ground into a powder and used to make a foamy material. Agricultural waste and wood fibres were experimented with in a similar way.

"We tried a bunch of different materials, but most of them turned out as rigid foam, not flexible," she says.

But eventually Ms Sandberg hit on seaweed, which her team transformed into a powder and baked in a special oven.

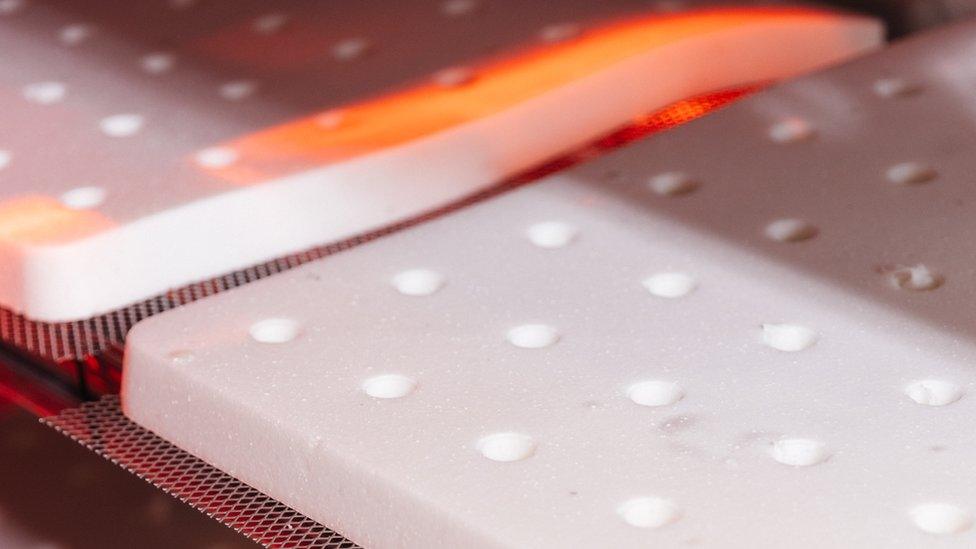

The process creates a foam block, soft enough to be used in seat cushions and chairs.

"The foam is 100% biodegradable. You can simply leave it in the soil, and it will naturally degrade over eight months - faster if you cut it into smaller pieces," says Ms Sandberg.

Agoprene is now looking to scale-up production by moving to a larger manufacturing facility in the coming year.

Agoprene's foam is baked in an oven

Can such innovation move furniture away from plastic, which is used in numerous ways in the furniture industry?

As well as polyurethane, which provides cushioning, the outside of soft furnishings might contain polyester - also part of the plastic family.

Faux leather furniture might use a vinyl blend, and vinyl is a convenient shorthand for a whole class of plastics. Meanwhile, cheaper wood furniture is often just a wood veneer stuck to plastic.

Industrially-produced wood furniture is often coated in a blend of chemicals, which may include polymers. That's what gives the wood that glossy, plastic-like appearance.

There are good reasons why plastic is so common, explains Christian Euler, an assistant professor in chemical engineering at the University of Waterloo in Ontario.

"It performs very well for its intended functions, and has a high degree of flexibility which allows it be soft or hard," he says.

"Also, because plastic's chemicals come from by-products from oil refining, it's cheap to make."

But there are serious downsides to cheap, plastic-laden furniture. For a start, more and more of it is being thrown away.

The Environmental Protection Agency in the US estimates that 12 million tonnes of furniture was discarded in 2018, up from eight million tonnes in 2000.

Around 80% of that furniture discarded in 2018 in the US ended up in landfill, where the plastic parts could take hundreds of years, external to break down.

Meanwhile, making the plastic that goes into furniture involves carbon emissions. According to Agropene's calculations, polyurethane foam rubber accounts for a 105 million tonnes of CO2 emissions every year.

So numerous firms are looking for alternative materials.

Mater chairs contain discarded coffee bean shells

Danish design company Mater has produced a line of chairs that feature seats and backrests made from materials blended with either discarded coffee bean shells or sawdust from furniture production.

Its outdoor furniture is composed of ocean waste.

"We like mixing creativity with innovation," says chief executive Ketil Ardal.

"While it takes a lot of cash to manufacture these sustainable collections, and I get some grey hairs because of it, it's in our DNA to be a green company."

Beyond seaweed and coffee shell waste, another unusual option researchers are hoping may replace plastic is fungus.

Mycellium, the root-like and branching structure of a fungus, is the foundation behind BioKnit, a new type of textile developed by researchers at Newcastle Upon Tyne's Hub for Biotechnology in the Built Environment (HBBE).

The process starts with mycelium grown on a substrate such as sawdust, says Jane Scott, lead of the HBBE's Living Textiles Group, and then it's placed in a dark and humid environment so it binds and absorbs nutrients from the sawdust. Then it dehydrates in an oven-like device.

Researchers are experimenting with the fungus mycellium to create structures

She notes BioKnit is already being used by designers to make lampshades, for example.

Ms Scott says an advantage of this material is how it "decomposes since it's bio-based and doesn't use any binders or glue that wouldn't decompose in a landfill."

Major design brands are seeking to join smaller nimbler companies in ushering in sustainable materials into their furniture pieces. US kitchenware and home furnishings firm Williams Sonoma has said it's now using responsibly sourced cotton and recycled polyester, and IKEA plans to use only renewable and recycled materials in its products by 2030.

Ms Sandberg says she's encouraged to see the furniture industry open to changing its wasteful ways. "I thought this industry didn't want to try anything new and only stay with polyurethane, but they are open and curious and willing to test and try new products because they want to see change happen with the products they create."