What a falling inflation rate means for your finances

- Published

Inflation is slowing and wages are rising, so you might conclude we can all afford to let our hair down a little more during Christmas party season.

But before the champagne corks pop, everyone should know that by splashing out, the financial hangover could be painful and long-lasting.

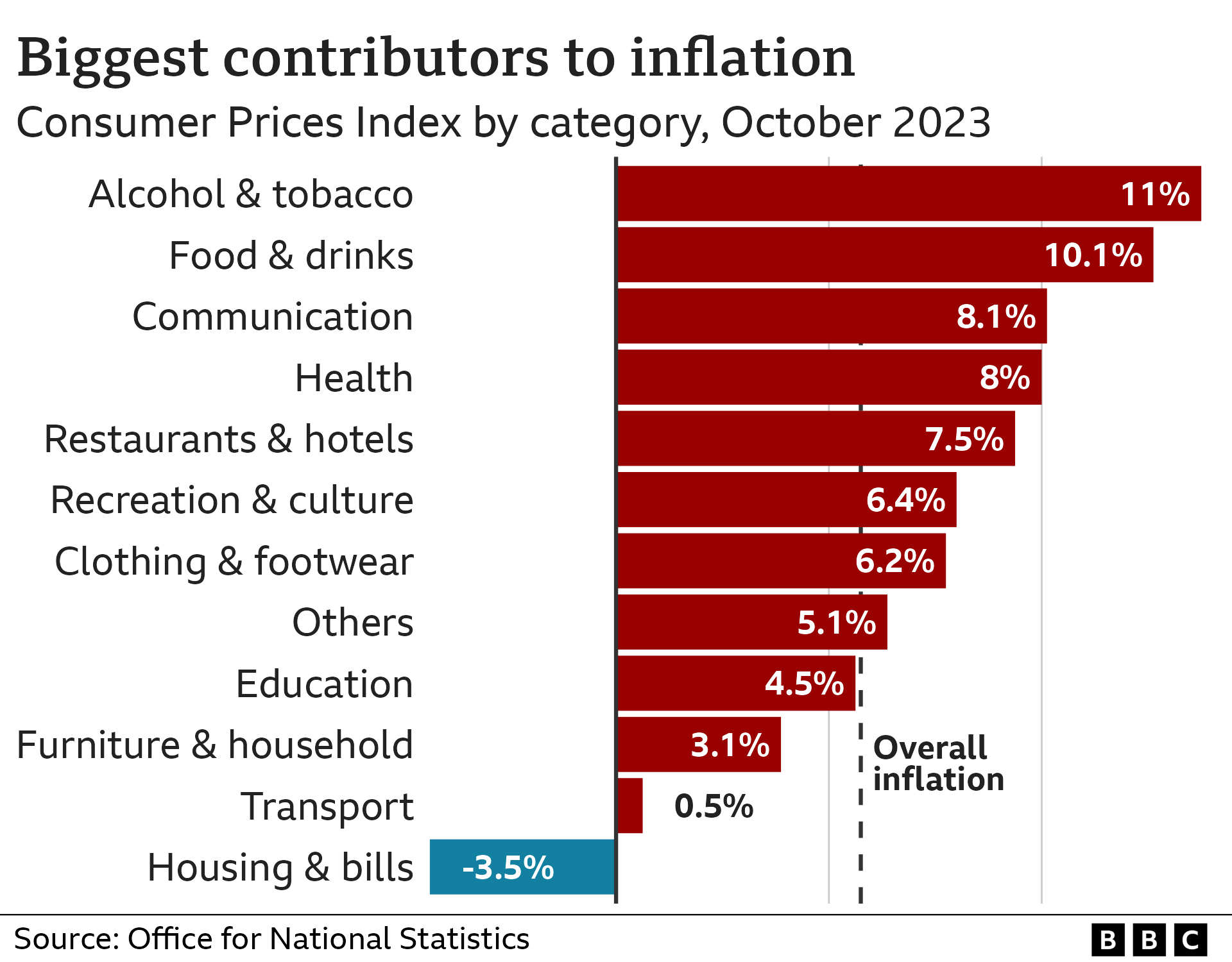

And that's not only because alcohol and tobacco prices are more than 10% higher than a year ago.

Official data on prices and on pay, published in the last two days, show that working people are typically better off in real terms than they were a year ago. In other words, wages are rising faster than prices.

But, make no mistake, prices are still going up, rising 4.6% in the year to October - a slower rate than they were, but still more than twice the target level. Bills are still high.

As everyone considers festive-related spending, primarily on non-essential items, charities warn that millions of people are under even greater pressure than a year ago when it comes to paying for necessities.

Energy prices down, but bills up

Household gas and electricity bills during the winter are a perfect example of the financial dilemma faced by families across the country.

Falling domestic energy prices are a key reason for the inflation rate going down. Yet, the typical household - so, millions of people - will actually be paying more for their gas and electricity this winter than they did a year ago.

How is that possible?

The key factor is a reduction in financial support from the government. Over the course of six months last winter, almost everyone received a £400 discount on their energy bills, funded by the government. That's not been repeated this year.

So, while the price of each unit of energy is lower, for the next few months (rather than the year as a whole), energy bills could be higher. And prices are likely to rise again in January.

Most people spread the cost over the year, through equal direct debit payments. But that's not the case for everyone, especially those on prepayment meters.

New data from Citizens Advice shows that the number of people who have been given crisis support, such as food bank referrals or energy top-ups, is higher so far this year than the same period last year.

It also says that people are arriving at its doors with a greater complexity of financial issues, rather than just one big problem.

Rocio Concha, director at the consumer group Which?, said: "While it's positive that inflation is falling, the cost of living is still increasing and consumers are paying significantly more for essential services."

She said the group's latest data suggested that 2.1 million households missed essential bill payments in one month alone.

Perhaps the most significant essentials we have to buy are food and drink - which remain one of the biggest contributors to rising prices, going up 10% in the last year. In simple terms, if a bottle of milk costs £1.10 versus £1 a year earlier, then annual milk inflation is 10%. Compared with two years ago, food prices are up by 30%.

The big supermarkets say they are dropping the prices of individual items but, overall, the typical cost of a weekly shop is still much more than it was a year or two ago.

How does inflation affect mortgages?

Policymakers will be considering all these factors, including consumers' ability to spend, the future direction of inflation, wages, and the strength - or otherwise - of the UK economy as a whole. Remember, there has been very little growth in our domestic economy over the last 18 months.

The impact on our finances is primarily through interest rates. The Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee has set the so-called benchmark rate at 5.25%, the highest it has been for 15 years.

Borrowing money has become much more expensive than people were accustomed to for more than a decade. Most strikingly, it is seen in mortgages with people rolling onto deals that may be hundreds of pounds more expensive each month than before. Mortgage pressure on landlords is a key reason for rents rising so rapidly.

Economists and the Bank liken the setting of interest rates to the shape of Table Mountain in South Africa, with its famous flat top.

The shape of Table Mountain offers a visual metaphor for interest rates

After 14 successive rises from December 2021, rates have been on hold for the last two months and are likely to plateau at the current level for a while yet.

And - as any mountaineer will tell you - complacency can make the descent more dangerous than the climb up.

While this all sounds depressing, there is support for those who are most at risk from financial difficulties.

Cost-of-living payments worth hundreds of pounds have helped to pay the bills. The government says these have given people a "significant boost". However, a committee of MPs recently said they had been insufficient for many people, external and the impact had been short-lived.

All eyes are now on Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, whose Autumn Statement in a week's time will reveal by how much benefits, pensions and the minimum wage will rise.

Speculation suggests he could try to make some savings for the government, meaning smaller-than-expected increases for benefit recipients.

That would create a political row and strengthen the need for everyone to take an even closer look at their income, outgoings, and budget - and perhaps to put the big Christmas party on ice for another year.

What can I do if I can't afford my energy bill?

Check your direct debit: Your monthly payment is based on your estimated energy use for the year. Your supplier can reduce your bill if your actual use is less than the estimation.

Pay what you can: If you can't meet your direct debit or quarterly payments, ask your supplier for an "able to pay plan" based on what you can afford.

Claim what you are entitled to: Check you are claiming all the benefits you can. The independent MoneyHelper, external website has a useful guide.

Related topics

- Published15 November 2023

- Published15 November 2023

- Published17 July 2024

- Published14 November 2023