The hidden tax rise in the Autumn Statement

- Published

- comments

Tax cuts were the main theme of the chancellor's Autumn Statement, but the policy decisions will not prevent taxes staying at their highest level on record.

A big part of that is due to a so-called "hidden" tax rise, one which can have a bigger impact on household incomes than others, known to economists as fiscal drag.

It sounds rather technical and dull, but it impacts millions of people.

The term describes a process in which more people are "dragged" into paying a larger amount of tax on their personal income - without tax rates going up at all.

While Jeremy Hunt announced a cut in National Insurance (NI) rates, he opted to leave NI and income tax thresholds untouched, meaning they remain frozen until 2028. Usually tax thresholds rise in line with inflation, the rate at which the prices in shops increase, but they have been kept the same since 2021.

A period of high inflation in recent times has led to many workers securing pay rises to ease the rising cost of living. But they are also paying more tax because a bigger portion of their income is taxed or they have been dragged into a higher tax band than before.

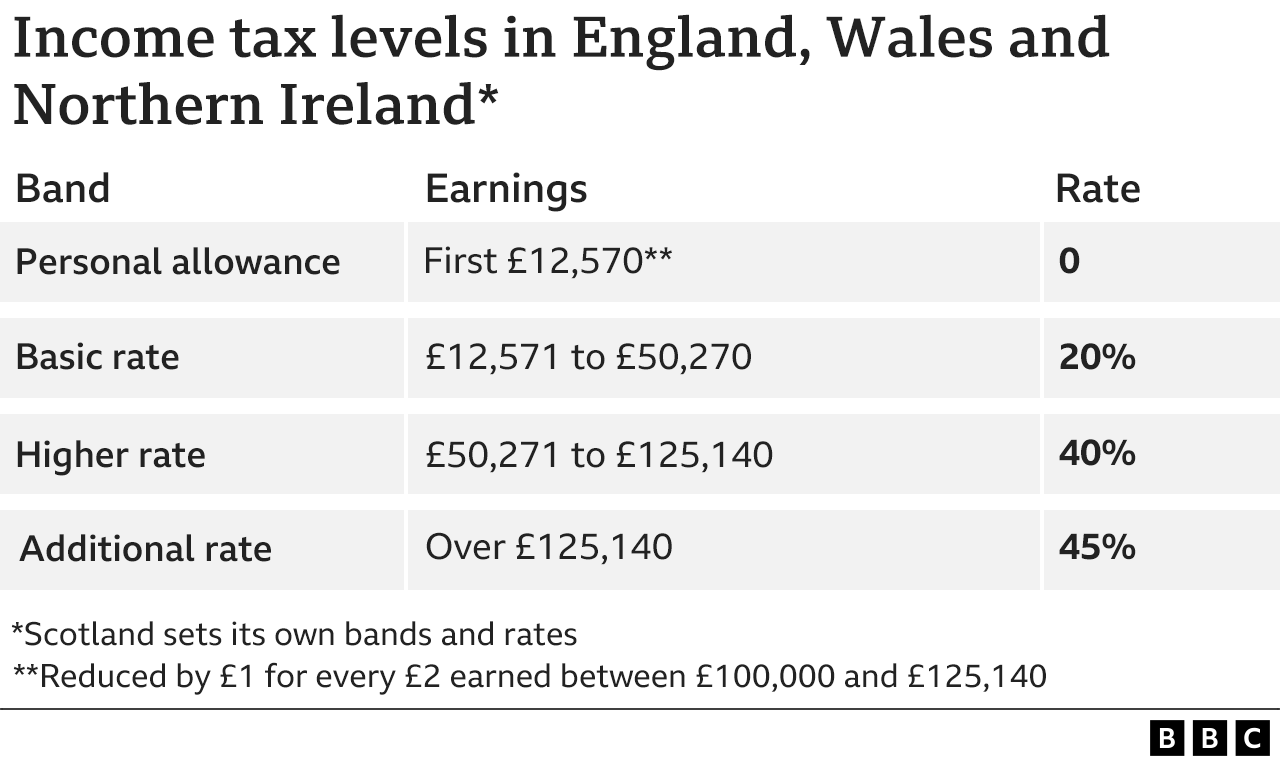

Some 2.2 million more workers now pay the basic rate income tax of 20% compared with three years ago, according to official figures, while 1.6 million more people have found themselves in the 40% tax bracket in the same period.

Critics describe freezing tax bands - the level at which a person starts paying different rates of tax on their earnings - as a "stealth tax" because the process happens gradually as a person starts earning a bit more.

The chancellor's cut in NI, which is a fixed percentage deducted from people's wages and goes towards the cost of benefits, the NHS and the state pension, will partially offset this so-called stealth tax.

But income tax revenues - the largest money maker for the Treasury - will continue to rise.

Sarah Coles, head of personal finance at Hargreaves Lansdown, said that while the 2% cut in NI "isn't to be sniffed at", by keeping NI and income tax bands frozen, "the Treasury has done nothing to protect us from the misery of fiscal drag, and means the lion's share of the damage done to our finances from these tax hikes will still continue to be felt years down the line".

"Fiscal drag is a powerful force, especially when tax thresholds are frozen in the face of an inflationary storm," added Laith Khalaf, head of investment at AJ Bell.

The UK's official forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), has estimated as a result of the policy, almost four million more people will be paying income tax and three million will move into the higher bracket by 2029.

Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies independent think tank, said the tax cuts for NI and businesses would not be enough to "prevent this from being the biggest tax raising Parliament in modern times".

"Higher inflation pushes up tax receipts by more than it pushes up spending on debt interest or social security benefits. But rather than use the proceeds to ease the ongoing 'fiscal drag' effects of threshold freezes, or to compensate public services for higher costs, the chancellor opted to cut other taxes - most notably National Insurance and corporation tax," he said.

The Resolution Foundation said households would on average be £1,900 worse off over the current parliament period from 2019 until the next general election.

"The truth is, taxes are up not down," said Torsten Bell, chief executive of the independent think tank which focuses on improving living standards for those on low to middle incomes.

"The cuts [in the Autumn Statement] are dwarfed by tax rises already under way."

- Published23 November 2023