The people creating digital clones of themselves

- Published

Rob Dix says is he now able to keep up with followers' questions

Property expert Rob Dix is now available to answer any question, at any time of the day, from his tens of thousands of followers. It is all thanks to cloning himself.

You might worry for one moment that there has recently been a huge medical breakthrough that somehow passed you by. But Mr Dix hasn't actually now got a physical, flesh and bone, copy of himself.

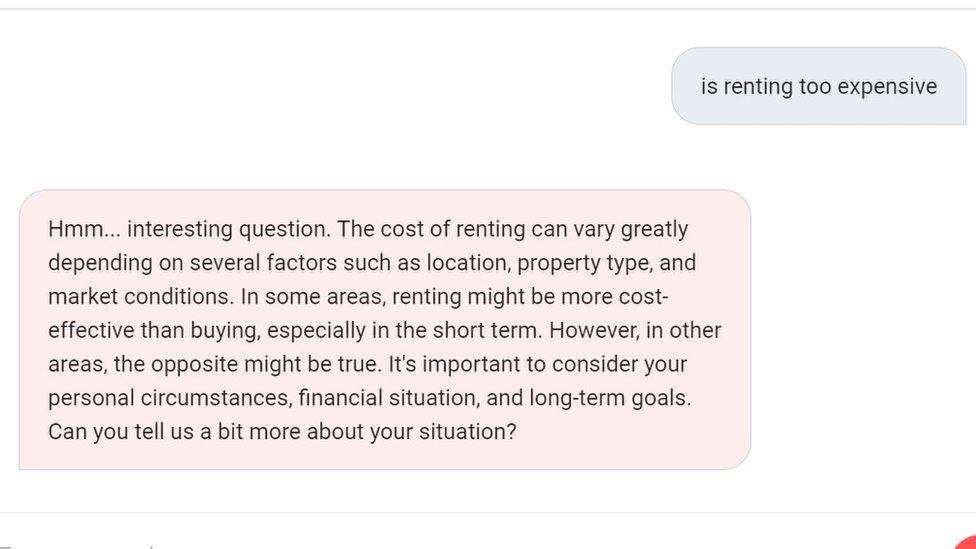

Instead he now has a digital clone on his website. Powered by artificial intelligence (AI) software it takes the form of a chatbot that can quickly answer questions as if it is him or his business partner Rob Bence typing their response.

Mr Dix created the clone by feeding it content, such as his books, the Sunday Times column he writes with Rob, and their show The Property Podcast. They say they have also trained the AI to write in their tone of voice.

"We answer questions from property investors in a weekly newspaper column and a phone-in show, but there are always far more questions than we can individually answer," says UK-based Mr Dix. "Yet most of the answers are embedded somewhere in the thousands of pieces of free educational content we've put out over the last 10 years.

"We've been able to organise all this information to coach people through their issues and find answers. As long as we train the AI with our words, our audience members get good responses to whatever they ask."

Coachvox AI allows users to set up a chatbox that represents them and speaks on their behalf

Mr Dix and Mr Bence are now two of around 150 people who have created AI clones of themselves through a UK company called Coachvox AI. The firm's other clients so far include chief executives, an astrologer, a nutritionist, a fitness coach, and even a marriage counsellor.

It is a small but fast-growing sector, and other providers of AI-powered clones include fellow UK business Synthesia and US start-up Delphi. The idea is that users can free up their time, with their digital clone taking on some of their workload, be it talking to employees, or offering advice to clients.

"Our AI clones bring useful, relevant guidance," says Coachvox AI's founder Jodie Cook.

Delphi also provides users with a text-based chatbot, and asks them to upload as much material they have on things they have previously written or said, including YouTube videos, podcasts, books or newspaper articles.

Using that material, Coachvox claims that a user's clone can "reason on new situations, rather than just regurgitate old anecdotes".

Synthesia goes further by adding video and sound. It allows users to create a talking avatar that appears on screen. You set this up by filming your head and shoulders, and speaking into a microphone.

Your avatar clone can then talk to clients, customers or staff members in more than 120 languages. The firm says the technology creates "a realistic digital version of yourself".

UK business coach Rose Radford is another person who has created her own digital clone to make extra use of her time.

"I spend a large number of hours per week answering questions from clients, so my first intention with an AI version of me was to allow my clients to have their questions answered instantly and any time of day, without needing my involvement," she says.

Rose Radford says she can now answer people's questions around the clock

This all sounds good, but what are the downsides?

"Making good content available for others who need it to advance in their career, or with their business, can provide a positive impact," says Prof Florian Stahl, an economist and AI expert at the Mannheim Center of Data Science in Germany.

"Yet, expectations regarding its quality must be appropriate. Business situations often grow so complex that not all relevant information can be provided in a chatbot prompt."

Dr Clare Walsh, director of education at the Institute of Analytics, a professional body for data science professionals, is even more cautious about AI clones.

"Modern day technologies work with partial awareness of the world they operate in, and that can be incredibly dangerous," she says. "Human experience is near infinite, and machines cannot be trusted to work with the many, many parameters out there."

Users of both Coachvox AI and Delphi can add an avatar picture

Mr Dix says he is careful to emphasise to users of his AI clone that they are dealing with technology rather than a real person.

"I feel a lot of responsibility when talking about money, so I was concerned that the AI might say things as 'me' that sounded too black-and-white, when in reality everyone's situation is different.

"We've had people say that, if anything, the AI goes too far in providing caveats and saying that the user should research further - but it's better that, than the other way around."

Additional reporting by Will Smale