UK economy falls unexpectedly in October as higher rates bite

- Published

- comments

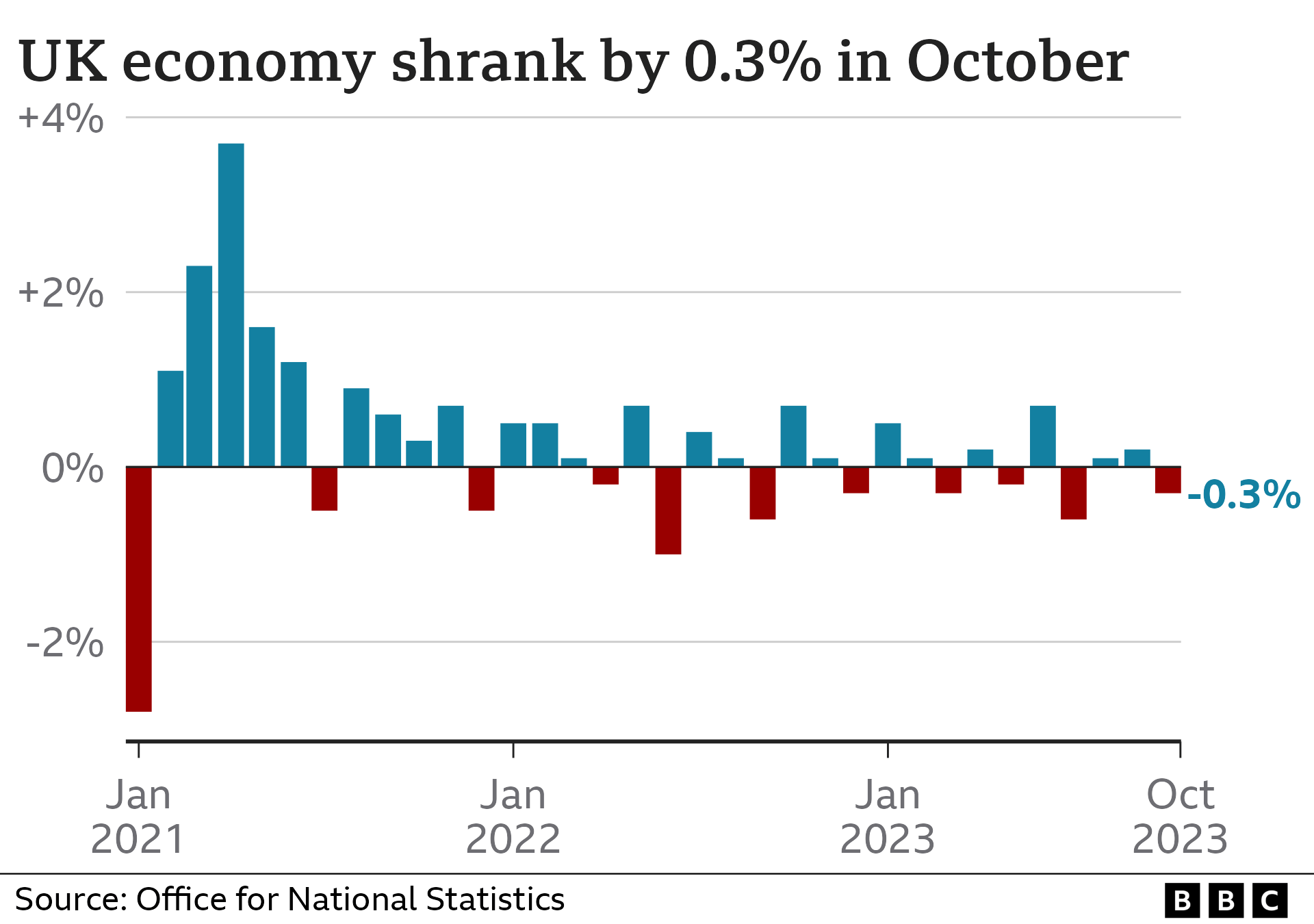

The UK economy shrank by more than expected in October, as higher interest rates squeezed consumers and bad weather swept the country.

The economy fell 0.3% during the month, after growth of 0.2% in September.

Household spending has been dented by rate rises as the Bank of England tries to tackle inflation. It is due to make its next rate decision on Thursday.

Meanwhile, retail and tourism were hit by severe weather in October as Storm Babet lashed the UK.

Most economists had predicted that the economy would shrink by just 0.1%, but the services, manufacturing and construction sectors all contracted.

The UK economy has been stagnating and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has promised to speed up growth.

But no significant pick-up is expected until January 2025, by which time the next general election must be held.

Commenting on the latest figures, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said it was "inevitable" economic growth would be subdued while "interest rates are doing their job to bring down inflation".

But shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves said growth was "going backwards leaving working people worse off".

According to the latest figures, external, the UK economy flatlined in the three months to October compared with the previous quarter.

The ONS said services had been "the biggest driver" of October's fall, with contraction seen in the IT, legal and film production sectors.

"These were also compounded by widespread falls in manufacturing and construction, which fell partly due to the poor weather, such as the severe winds and flooding seen during Storm Babet," said Darren Morgan, its director of economic statistics.

The latest estimates underline the ongoing impact of the cost-of-living crisis and the tools employed by policymakers.

Up until September, the Bank of England had raised interest rates 14 times in a row to try to tame inflation - which is the pace at which prices rise.

However, while raising rates can reduce inflation, it also affects economic growth by making it more expensive for consumers and businesses to borrow money.

Interest rates are at a 15-year high of 5.25%, and are expected to remain high for some time.

Against a difficult backdrop at his recent Autumn Statement, the chancellor promised to boost growth with measures to speed up investment in the private sector.

Mark Mills-Goodlet, managing director of second-hand car dealership Winchester Motor Group, told the BBC that businesses still faced big questions over whether to invest more in their companies now rates are higher, or to wait.

The company saw rapid growth for more than a decade, he said, but this had "slowed in the last couple of years... purely and simply because of the uncertainty in the market".

In the short-term, official forecasts suggest UK growth will remain fairly subdued due to those higher rates.

Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK, said the UK was likely to escape a recession but households would face further pain as around 1.5 million fixed-rate mortgages expire next year and people's repayments go up.

She believes the Bank of England will not raise interest rates at its next meeting on Thursday and is unlikely to start cutting them until inflation - currently at 4.6% - gets closer to the 2% target.

The Bank's governor, Andrew Bailey, recently warned that rate cuts would not happen for the "foreseeable future".

In an interview with local news website Chronicle Live during a visit to the North East of England, he said that he was concerned over the UK economy's potential to grow, adding: "There's no doubt it's lower than it has been in much of my working life."

Around the Autumn Statement, the government's independent forecaster slashed its growth outlook for the UK, partly due to high inflation and interest rates.

On Wednesday, the Resolution Foundation suggested that Britain was a "stagnation nation" due to poor productivity and a lack of investment in things like skills.

The think tank, which aims to improve the living standards of those on low to middle incomes, said the UK had grown by just 0.5% over the last 18 months - the weakest rate outside of a recession on record.

Achieving "stronger, sustained economic growth" was the only way to boost living standards and catch up with peers, said its research director James Smith.

- Published12 December 2023

- Published10 November 2023