Oil prices rise on US-UK strikes over Red Sea attacks

- Published

Oil prices jumped by 4% after the US and UK launched strikes in Yemen over recent attacks by Houthi rebels on ships in the Red Sea.

Brent crude hit $80 per barrel for the first time this year as the Iran-backed rebels vowed to retaliate against military action by Western powers.

While the price rose, it is below highs reached when Russia invaded Ukraine.

But the UK government has drawn up scenarios suggesting further disruption could hit the economy.

The BBC understands the Treasury has modelled outcomes including crude oil prices rising by more than $10 a barrel and a 25% increase in natural gas.

On Friday, Brent Crude - the international benchmark for oil prices for much of the world - hit $80.71 per barrel before easing, while US West Texas crude increased by 2.79% to $74.03.

The UK government is concerned that ongoing attacks on shipping in the Red Sea could weigh on the UK economy, where growth remains fragile.

Higher energy prices risk stoking inflation just as it has begun to slow. Meanwhile, the cost of shipping containers on vessels has jumped, meaning that companies could choose to pass on this expense to consumers.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said that the attacks had caused "major disruption to a vital trade route and [higher] commodity prices".

But Simon French, chief economist of Panmure Gordon, pointed out that energy prices are still considerably lower than they were four months ago.

"At these levels, it is actually quite disinflationary for the UK economy," he said.

He added that when the Bank of England comes to make its next interest rate decision in February, oil prices are still likely to be some 20% lower than they were in the autumn.

More on the US-UK strikes in Yemen

Houthi rebels in Yemen have stepped up attacks on commercial vessels since the start of the Israel-Hamas war in October. The US said there had been 27 attacks in the Red Sea since mid-November.

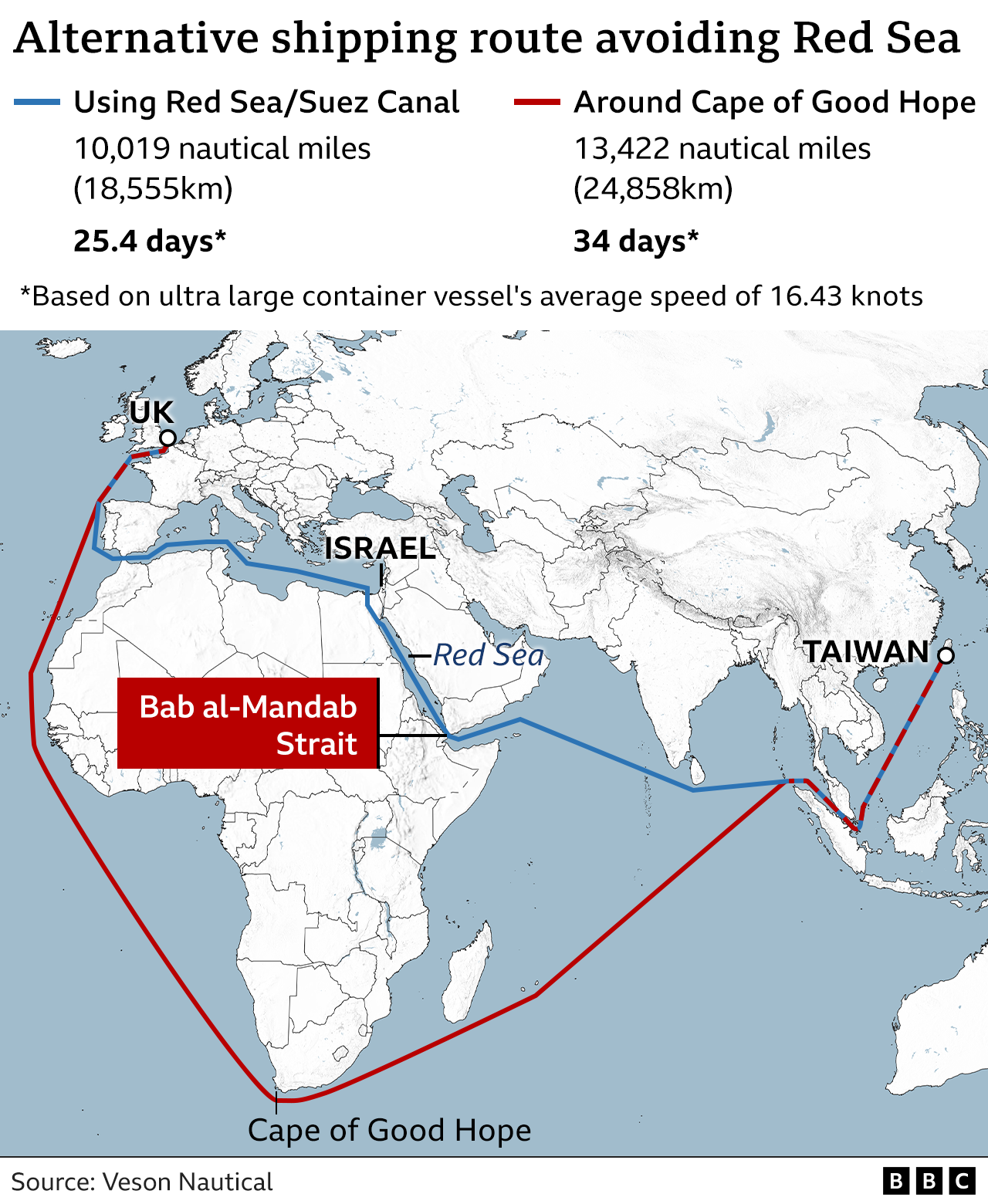

The group has been using drones and rockets against foreign-owned vessels transporting goods through the strait of Bab al-Mandab - a 20-mile wide channel that splits Eritrea and Djibouti on the African side and Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula.

Ships usually take this key trade route from the south to reach Egypt's Suez Canal further north. Many companies are now sending vessels around the Cape of Good Hope instead, a route that adds at least 10 days of travel.

On Friday, shipping data showed that at least four oil tankers changed course since the overnight strikes by the US and the UK.

Danish fuel tanker giant Torm also said that it had stopped allowing its fleet to sail through the southern Red Sea, while Intertanko, which represents nearly 70% of all internationally traded oil, gas and chemical tankers, is currently urging its members to avoid the Bal al-Mandab straight for several days and turn off their transmitters.

About a quarter of the world's shipping containers are being diverted.

According to the White House, external, about 15% of global seaborne trade passes through the Red Sea. This includes 8% of global grain, 12% of seaborne oil and 8% of the world's liquified natural gas.

Vincent Clerc, chief executive of Maersk, the shipping giant, told the BBC that "significant disruption" to global trade was already being felt "down to the end consumer".

Several companies have said they have already seen, or are expecting, a knock-on effect:

Carmaker Stellantis is using some airfreight solutions to avoid disruption

Tesla has suspended most car production at its Berlin plant

Volvo Cars will pause production for three days next week at its plant in Ghent, Belgium

Tesco's boss has warned it "could inflate the cost of some items"

Next has said delays to deliveries could arise

Ikea has said supplies could be affected

Danone has said transit times for its shipments have increased

The Houthi group has declared its support for Hamas and has said it is targeting ships travelling to Israel, although it is not clear if all the ships that have been attacked were actually heading to Israel.

As a result of the attacks, Maersk and several of the world's other major shipping lines have been avoiding a key route for global trade as they prioritise the safety of their crews.

"We have ships that are being shot at. We have colleagues whose lives are at risk when this happens and we can simply not justify sailing through these danger zones the way the situation is right now," Mr Clerc said.

He said the longer route around Africa was sucking capacity out of the global shipping system in the short term, adding anything from seven days to two weeks to a ship's journey, as well as costing $1m (£783,000) more in fuel alone.

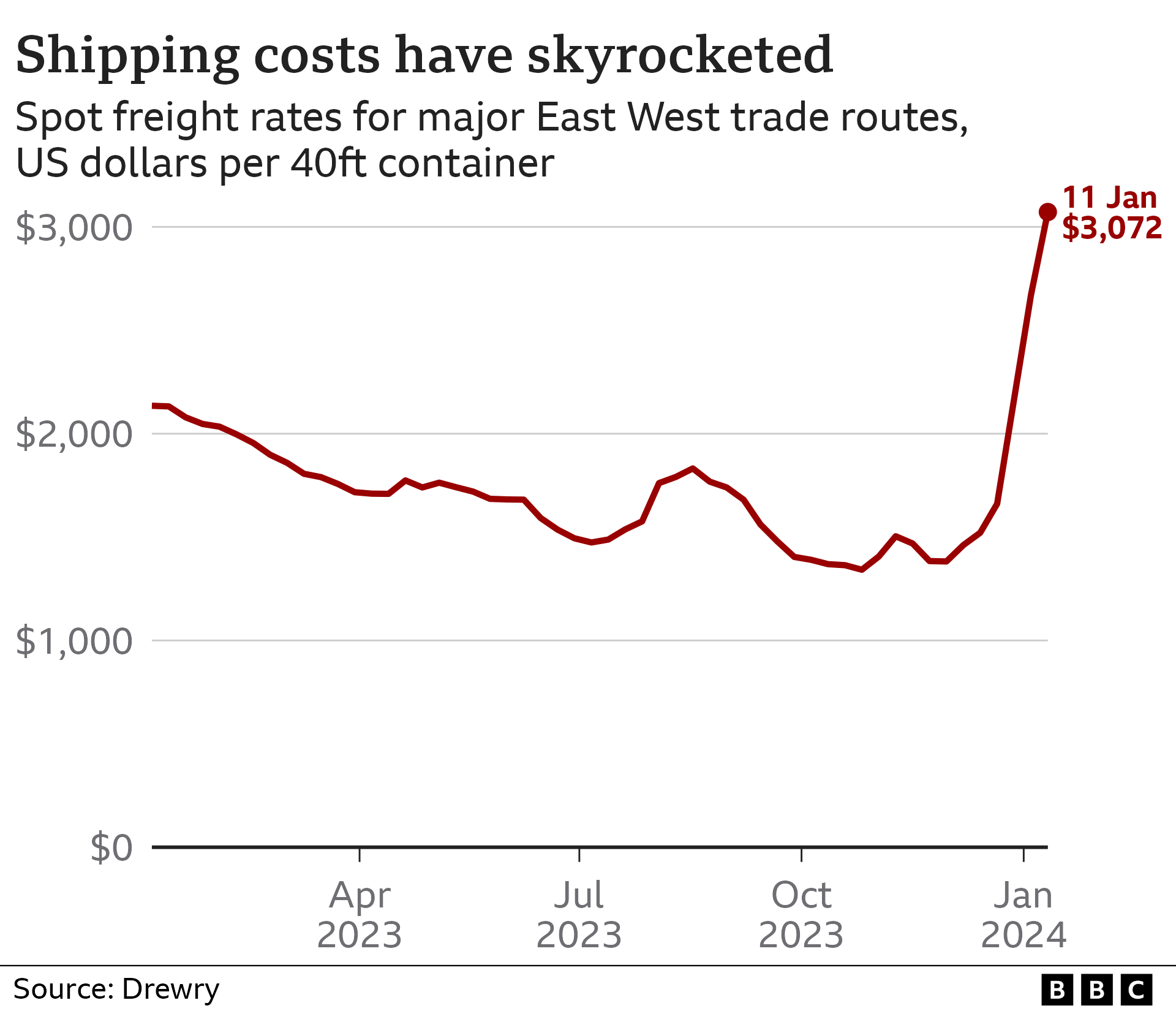

Rates for moving cargo by sea reached record highs during the pandemic. Since the attacks on vessels started in the region, prices for both container transport and that of goods have again surged.

According to the Drewry World Container Index, pricing for a 40ft container hit $3,072 on 11 January, prior to the US and UK strikes carried out on Houthi targets in Yemen.

In Bahrain on a tour of the Middle East this week, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said extra costs get "translated into higher prices for people, for everything from fuel to medicine to food".

"And so it's having a real impact on people around the world in their daily lives."

- Published25 March

- Published11 January 2024