WASPI: Minister calls for time in women's pension row

- Published

A minister has refused to confirm whether the government will pay compensation to women hit by the rise in the state pension age.

The Women Against State Pension Inequality (WASPI) campaign group says they were not properly informed about the change.

An ombudsman last week recommended that the women receive an apology and pay-outs of between £1,000 and £2,950.

Mel Stride told the Commons its report would be "properly" considered.

Labour also failed to say what it would do regarding compensation, but called on the Work and Pensions Secretary to return to the Commons quickly.

The SNP asked whether another TV drama was needed to "embarrass and shame them into doing the right thing", in reference to the television series which elevated the plight of sub-postmasters and postmistresses who have been fighting for compensation in their battle against the Post Office.

Meanwhile, the chair of the WASPI campaign group, Angela Madden told the BBC the minister made references to the report being 100 pages long "as if he were being asked to digest War and Peace".

"The fact it is has taken five years for the ombudsman to produce his conclusions is a pretty perverse reason to say more delay is now justified," she said. "The report is not complicated at all...

"The Commons must get a debate and vote on compensation as soon as possible after Easter."

While Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has hinted at the possibility of a pay-out, the chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, was not drawn on the possibility when asked over the weekend.

Instead, he committed to the future of the triple-lock state pension pledge if the Conservatives continued in government after the election.

Key review

A long-awaited report by the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO) was published on Thursday. It spent five years looking at whether some women were properly informed of the rise in the state pension age to bring them into line with men, not the equalisation policy.

On the sample of cases it considered, it said there was injustice and an apology and compensation should be forthcoming. The ombudsman can recommend compensation, but cannot enforce it.

It added that up to now the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) had "clearly indicated it will refuse to comply" on its pay-out proposal, which it said was "unacceptable".

Mr Stride said only some women were affected and that involved communication between 2005 and 2007.

But he told MPs the ombudsman did not find that women had "directly lost out financially as a result of DWP's actions".

He quoted from the report that the ombudsman did "not find that it [meaning DWP's communication] resulted in them [referring to the complainants] suffering direct financial loss".

However, he acknowledged there were "strong feelings" involved and said there would be "no undue delay" in coming back to Parliament with an update.

'Devastating impact'

Audrey Evans, 66, from Nottingham, says she feels "really aggrieved that the government have changed the age as they went along".

"They haven't considered the impact on women," she says, adding that people who were born in the 1950s tended to work from a much younger age.

She was just 14 when she started working full-time in a sewing machine factory.

Audrey Evans says the government "robbed" her of precious retirement years with her husband

Eventually she qualified as a nurse and spent the rest of her career in the caring profession.

Having to postpone retirement had a "devastating impact" on her life as her husband is nine years older, so he was 74 before they could retire together.

"That's a massive gap in the quality of retired life together," she says. "The government basically robbed us of precious years together, a total injustice."

The possibility of compensation "would be some recognition that we were hardly done by," she says, but it "would have been better had we had a pension from 60".

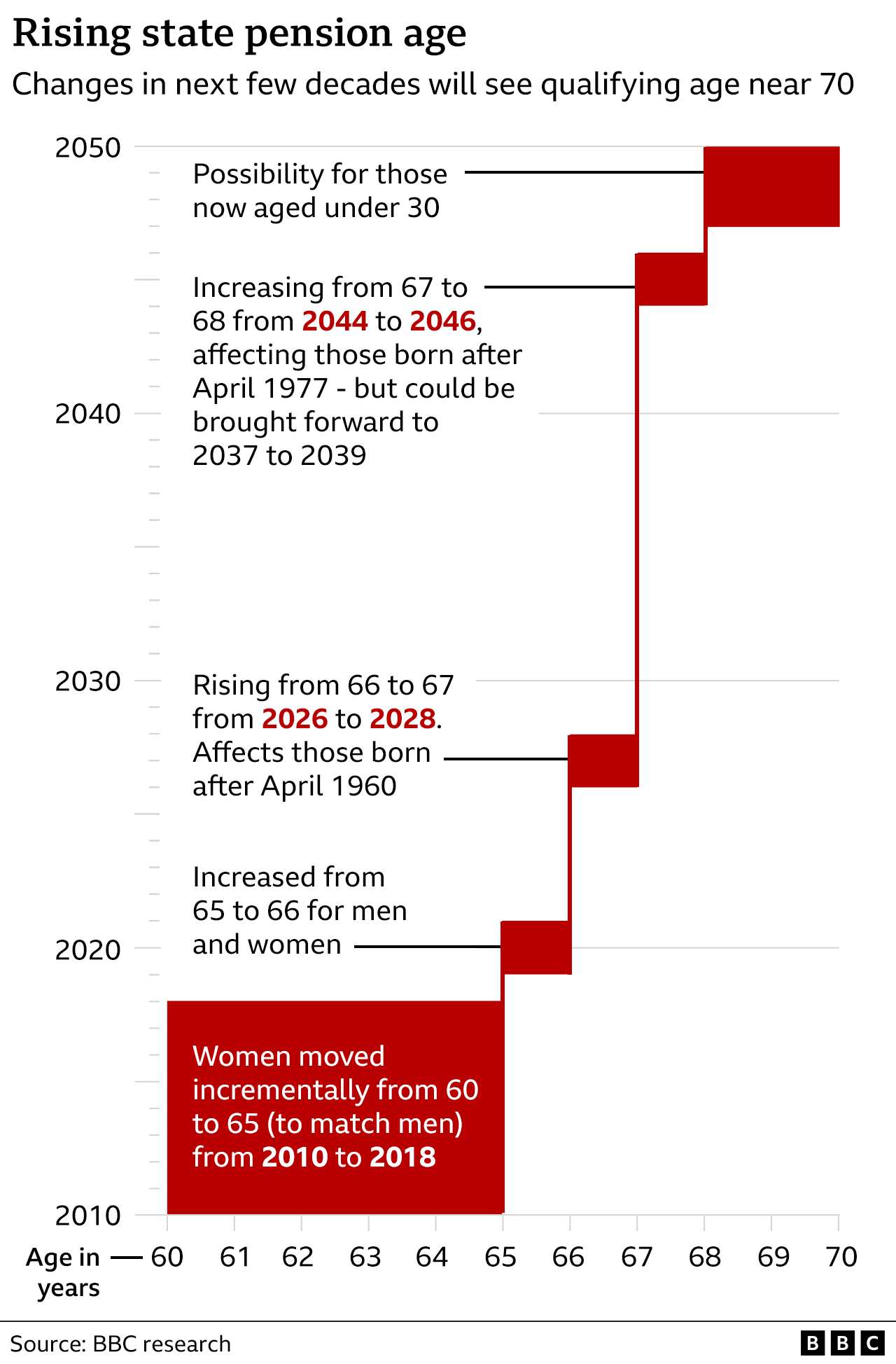

The age at which people receive the state pension has been increasing as people live longer, and currently stands at 66 for men and women. But for decades, men received their state pension at 65 and women at the age of 60.

Under the 1995 Pensions Act a timetable was drawn up to equalise the age at which men and women could draw their state pension. The plan was to raise the qualifying age for women to 65 and to phase in that change from 2010 to 2020.

But the coalition government of 2010 decided to speed that up. Under the 2011 Pensions Act the new qualifying age of 65 for women was brought forward to 2018.

The increases have been controversial. Campaigners claim women born in the 1950s have been treated unfairly by the rapid changes and the way they were communicated to those affected.

Many thousands said they had no idea they would have to wait longer to receive their state pension, and had suffered financial and emotional distress as a result.

Related topics

- Published18 December 2024

- Published21 March 2024

- Published21 March 2024