How fraudsters are getting fake articles onto Facebook

- Published

- comments

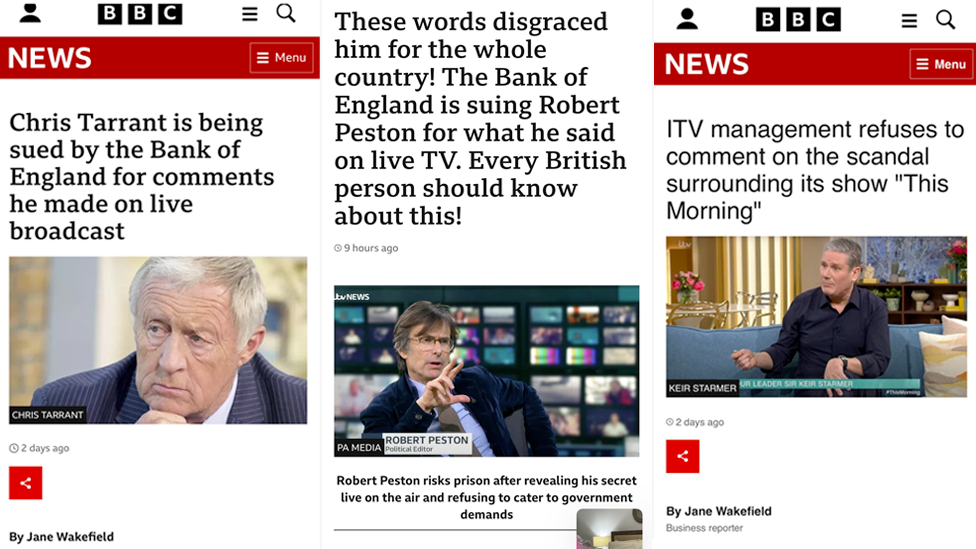

Examples of fake articles that have appeared on Facebook and Instagram

I have been really busy recently, writing articles about famous people.

I've done interviews with the likes of Zoe Ball, Jeremy Clarkson and Chris Tarrant.

There has been a common theme to these stories, and it is all about how each celebrity made vast sums of money from an online investment opportunity in crypto currencies.

And if this all sounds a bit unbelievable, that's because it is - I hadn't done a single one of these interviews, nor written any of the articles. And none of the famous people involved, or me, would dream of endorsing crypto investments of any kind.

Instead, the fake stories were all AI-generated scams that appeared on Facebook news feeds in a BBC template, and with my byline.

The fraudsters behind them hope that people will click through to the full article, and from there be tempted to invest in a fake investment scheme being promoted on the page.

I was curious as to how these scam posts were getting onto Facebook in the first place, so I contacted Tony Gee, a senior consultant at cybersecurity firm Penn Test Partners.

Tony Gee says that the fraudsters are simply able to change the website links

After examining the URL, or web address, of one scam page he said it was most likely a paid-for Facebook advert.

Mr Gee said he could tell that because the URL had a unique value that Facebook adds to allow it to track outbound clicks.

I put this finding to Facebook's owner Meta, who said: "We don't allow fraudulent activity on our platforms, and have removed the ads brought to our attention."

But how are the scammers able to get the fake ads onto Facebook news feeds in the first place? How can they get past Facebook's automated detection systems?

Prof Alan Woodward, a computer scientist at the University of Surrey, says the criminals appear to be using tools that very quickly redirect users to another web page.

So when the advert is first placed with Facebook, the link goes through to a harmless page, one that doesn't try to con you out of your cash. But then once this has been approved by Facebook, the fraudsters then put on a redirect that instantly takes people somewhere else - to a web page that very much wants to maliciously dent your bank account.

"If you control a website then it is relatively easy to include a redirect command, such that before someone's browser has had a chance to show them the original webpage, their browser is sent to an alternative one," says Prof Woodward.

He adds that the fraudsters can quickly and easily keep changing the destination of the redirect. "As soon as you are able to obfuscate the true nature of a URL, that is manna for scammers," he says.

This is a type of online fraud called "cloaking", whereby malicious adverts are able to get past a social media firm's review stage because the fraudsters have hidden their intentions.

Meta says it is using what it has learnt about this technique to improve its automated detection systems.

Margaret (not her real name) is a retiree who lives in Buckinghamshire. She was recently conned out of £250 when she fell victim to fake advert on Instagram, which is also owned by Meta.

She had been tempted to click on a link to a fictitious ITV article in which presenter Robert Peston (or rather, a scammer pretending it was him), chats about an investment opportunity he had come across. Margaret who trusts Mr Peston and the ITV brand decided to invest.

In addition to paying the £250, Margaret sent off pictures of her passport, and both sides of her credit card. She immediately started getting phone calls.

"It was someone with an American accent welcoming me and saying my money was already making money," she tells me.

The phone calls kept coming, as did a torrent of emails. Margaret became suspicious, particularly when they started asking her about her income and savings, and when she intended to invest more money.

"I contacted my bank and was refunded but it didn't stop the scammers."

Margaret still receives daily calls, and even started getting them from someone purporting to be from the US National Security Agency promising to help her investigate the scam.

"My own mental health is being impacted and I believe I am at risk, in particular identity theft and indeed potential monetary theft," she says. "They are so mega persistent, and are dangerous pests."

It is an issue that UK consumer watchdog Which? has been looking into.

"Malicious advertisers may mask web links or impersonate trusted brands such as the BBC to evade online platforms' reporting systems, and people often don't know they're looking at a scam or a deepfake until it's too late," says Rocio Concha, its director of policy and advocacy.

"It should not fall on consumers to protect themselves from this fraudulent content online. Ofcom must use its powers under the Online Safety Act [which was passed late last year] to ensure that online platforms are verifying the legitimacy of their advertisers to prevent scammers reaching consumers."

Ofcom said in a statement that tackling fraud "is a priority" for the regulator.

"The UK's new online safety laws will be an important part of making it harder for fraudsters to operate," it added. "Under the new laws, online services will be required to assess the risk of their users being harmed by illegal content on their platforms - including fraud, take appropriate steps to protect their users, and remove illegal content when they identify it or are told about it."

Nicolas Corry says that social media firms need to put more effort into checking each and every advert

Nicolas Corry is managing director at financial investigation firm Skadi. He says he was "troubled" by the amount of causal fraud occurring on Facebook and other social media sites.

"These companies are making vast amounts of profits, and exposing people to fraud," he adds. "And then it's the finance companies that pay for this, or the victims themselves."

Mr Corry says social media firms should be more rigorously checking each advert, and its links, before they allow them to go up.