Eurozone: No safe haven

- Published

- comments

We don't know yet whether any countries will end up leaving the euro. We do know that quite a few investors are.

The ECB's latest balance of payments report shows there was a record 59.4bn euros net outflow of portfolio investment from the eurozone in the first three months of 2012.

Of course, the numbers for individual countries are in even more shocking: yesterday we found out that nearly 100bn euros had fled the Spanish banking system in the first quarter.

I discussed the options for Spain and its banks, and its government's desire to get help from the European Central Bank, on the Today programme this morning., external

In many ways, the flow of private investor cash from the periphery countries, and the eurozone itself, is the price that European leaders pay for the "muddle through" approach to the crisis.

This is something that Robert Peston and I have gone on about many times before, which has now been given added drama by recent events in Greece and Spain. But we should never forget what the drying up of private investor cash means for the real economy.

This is brought out in some new and rather frightening numbers pulled together this week by the economist David Owen from Jefferies International.

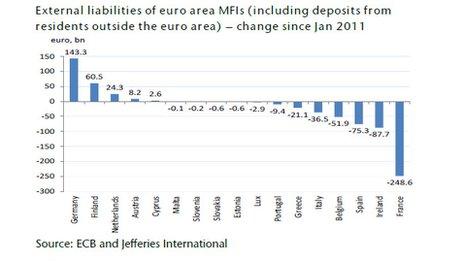

There are plenty of scary charts to choose from: let me just show you two. This first one shows the change in foreign liabilities of banks - including deposits by non-residents - in each eurozone country since the start of 2011.

As you can see, there have been a significant inflow of funds for Germany, as you'd expect. It also shows very large outflows from Spain, Ireland and - more surprisingly - France. (Though remember France is a much bigger economy. Relative to the size of the banking system, the outflow from the periphery countries would be much greater.)

As we know, the outflow of money has left the ECB in the awkward position of filling the gap. But it's worth remembering why there is a gap in the first place - why the periphery countries need to borrow a large amount from the outside world.

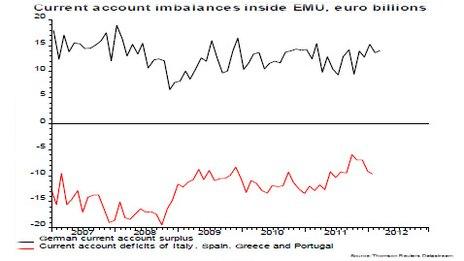

These countries need the money because, as this second chart shows, even after three years of austerity and crisis, with the exception of Ireland, all of the economies in crisis are still importing a lot more stuff than they export.

That's a useful reminder of the economic problems at the heart of this crisis: what looks like a banking crisis in Spain and the rest is just as much a crisis of competitiveness. And what looks like ECB emergency liquidity for periphery banks is just as much balance of payments financing for the entire economy - something that has previously tended to be provided by the IMF. (I went into this distinction in greater depth a while ago).

These are not comforting thoughts: as Paul Krugman said to me earlier this week on his trip to London, if the eurozone is going to end, it's a fair bet that the process will start with a Spanish bank run - and a tussle with the ECB.

However, this being Diamond Jubilee weekend, I've found you one important upside to all this. You just have to move to America to enjoy it.

All those investors rushing for safe US assets have helped to push down the cost of borrowing to new lows, not just for Uncle Sam but anyone in the US taking out a new mortgage.

The average interest rate on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage in the US is now just over 3.9%. The interest rate on 10-year government bonds is barely 2%.

The eurozone can't take all the credit for that - the Federal Reserve's commitment to keep its official interest so low is clearly a big part of it. But safe haven flows have played their role as well.

I suspect President Obama wouldn't mind losing some of those flows - or seeing a rise in long-term borrowing costs - if it meant he could stop worrying that the eurozone was about to blow up. He can join the club.