Putting the fizz back into Catalonia's cava

- Published

Cava's producers have gone for the mass market, but this means low profit margins

Cava, Spain's sparkling wine, has an image problem and its producers are seeking to rebrand it in a bid to put back the fizz into its sales.

"The problem with cava is perception, not quality," says Josep Puig, general manager and CEO of Sumarroca winery.

"If the price is low it gives a bad perception." He bemoans the fact that for years the larger cava houses have chased the mass market with low prices - it hasn't worked out.

The UK sparkling wine market grew 37% between 2012 and 2016, but Spain's cava is losing out to Italy's prosecco.

The UK bought over seven million cases of prosecco in 2016, up 12% on the year before, compared to just under two million cases of cava, a drop of 15%.

Cava sales in the UK are declining

And in a survey of Brits, when it came to quality, 64% chose champagne, 22% prosecco and just 14% cava.

Adding to cava's woes has been Catalonia's political turmoil - 95% of cava comes from Catalonia but some Spaniards opposed to Catalan independence have called for a boycott, which could further damage the industry.

"Cava's image doesn't allow us to earn any money. It's OK for the big producers but it's impossible for the smaller wineries to compete at such low prices," says Josep Maria Albet i Noya.

He used to produce cava but four years ago formed a break-away group with others. They now call their drink "classic penedes".

Josep Maria Albet i Noya says cava's cheap image makes it impossible for smaller wineries to compete

He says when he stopped making cava, you could buy a bottle in the local supermarket for under one euro.

"You can't earn anything with that, when your margins are so small you have to squeeze everybody. Your product will reflect this in low quality - I don't think that's the way forward."

In April, six more producers distanced themselves from the cava name, arguing that the Spanish denominacion de origen (DO) had over-produced cheap fizz, thereby damaging its image.

They intend to market their product under a new name - corpinnat.

Albert Puig, a wine consultant and cava expert from the Penedes area, in the heart of the cava region. says: "If you do good things you can have the high price - but if you compete on quantity then you're lost."

Catalonia's political turmoil has also added to the cava industry's woes

Pere Bonet, who is also a member of the Freixenet family, the largest cava house, agrees: "For the brands, the low cost is dead."

Yet aren't Freixenet and the other cava houses to blame for selling too cheaply? "Yes, of course," he responds. "Our objective [now] is to have a better image for the brand."

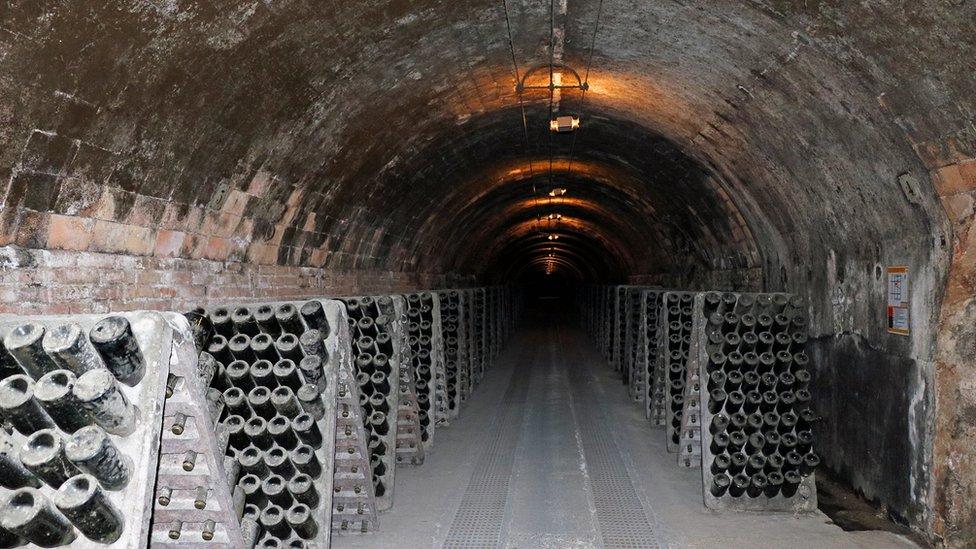

He says international sales are doing well but that profit margins are still too low. To tackle this they have introduced a premium category, called cava de paraje calificado.

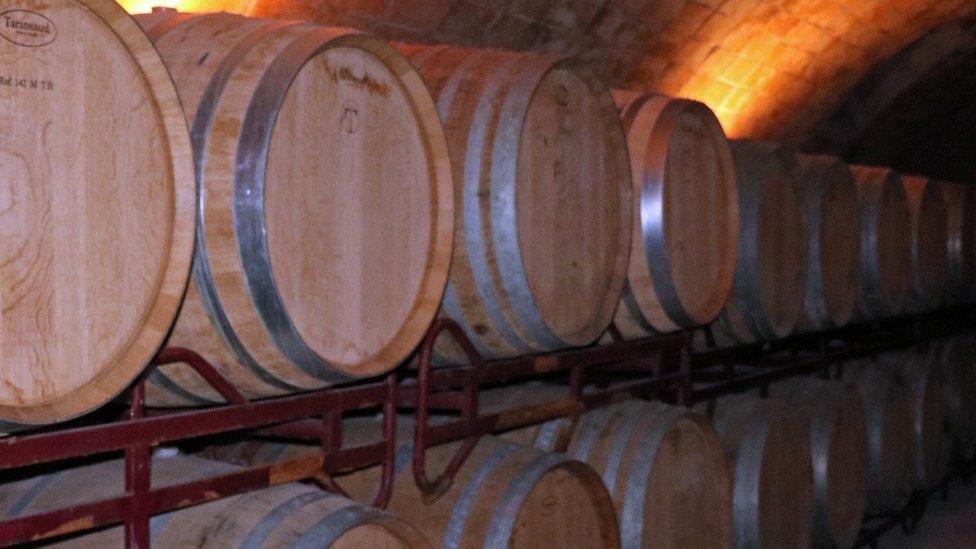

Producers have to meet stringent guidelines: the vines must be at least 10 years old; the grapes must come from a specific vineyard; there are restrictions on grape yields and the wine must be aged for at least three years in the bottle in cavas close to the vineyards.

And there are then various tests for the sparkling wine to go through. So far only 12 cavas from nine producers have attained the new qualification.

"We don't have a unique selling point," says cava producer Josep Puig

Yet these wines will only ever account for about 1% of total production. "The deal is," says Pere Bonet, "that these special cavas can show the excellence of cava in general."

Not everyone believes this will work. Josep Puig of Sumarroca is one of the doubters: "It will collapse. We need to boost the general image of cava and we don't have a unique selling point."

Spending more on marketing is his answer: "If you don't promote something you'll find young people start thinking cava is something strange and they'll go for prosecco instead."

"You need a unique selling proposition; and you need money to have a unique selling proposition."

Codorniu has already decided to move its financial headquarters out of Catalonia

Another headache for cava has been Catalan politics, and the calls for independence.

Codorniu has already decided to move its financial headquarters out of the region and the largest producer, Freixenet, is considering it.

Pere Bonet says any breakaway from Spain would be concerning, especially if the EU were to then impose tariffs: "We export to Europe - to Belgium, to Germany - more cava than we do to Spain. For some brands who export to Europe in big quantities, independence could be a disaster."

Yet for smaller producers who only sell in Spain there are gains to be made, and some are taking advantage of the political turmoil, says Albert Puig: "Because of the political problems production outside Catalonia has boomed 100% every year. They sell saying 'this cava is not made in Catalonia'."

Those on the other side of the argument, say Catalonia and cava can survive perfectly well without Spain, that they can find better markets elsewhere. But cava's main challenge remains - being able to re-brand itself as something truly special.

You can hear more from John Murphy on Radio 4's From Our Own Correspondent, and more on the cava industry's bid to re-invent itself on Radio 4's In Business programme.