How schizophrenia changed the whole course of my life

- Published

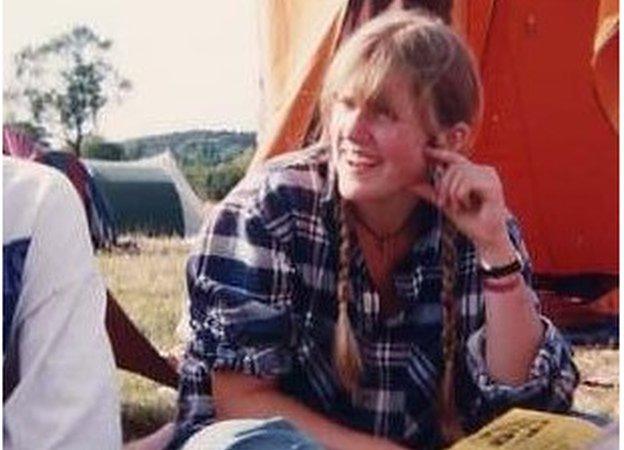

Alice Evans was at university when she developed schizophrenia. She didn't leave her parents' house for the next ten years.

I was about 20 and studying at university when I first became seriously unwell. I'd come from a small rural village in Devon, with my bags in tow, and it was the first time I'd even really been to a city.

When I got to university it was daunting for me to be away from home but I made some friends, and was enjoying my drama course. I couldn't shake depressive thoughts I'd had during my teenage years though.

I was working three jobs to make my rent and on top of my degree it proved to be too much.

Eventually I stopped sleeping entirely and that was when the problems really started.

I felt like the world had lost its colour. It's the only way I can describe it. Everything went a drab, boring shade of grey.

Alice was at university when she first experienced hallucinations

Thoughts and sentences began to disappear from my mind. I would think of something and then it would just go. Poof! And I couldn't speak. The words just wouldn't physically come out of my mouth.

I was frightened all of the time, especially when I began to hear other voices on the radio and TV. I didn't know what was happening and had no idea how ill I already was.

One weekend I had a visit from my aunt and uncle and as we were walking around the city I became aware that there were no people around, they had suddenly disappeared and all the buildings had collapsed. I was walking completely on my own in an abandoned city.

Of course this wasn't actually happening but when you are in the middle of a psychotic episode that experience of the world is your reality. It isn't as though you can click your fingers and go back to normal. It's not an option.

That period of my life is incredibly hazy for me, I was so confused, scared and tired that I really don't remember much from that time.

And because I couldn't talk, I wasn't able to tell my friends and family how serious it had become. In fact I don't think I even realised. When you experience psychosis most of the time you are too frightened to speak.

One day I left my house, disorientated and with no idea of where I was going. With nobody there to help I wandered the streets of the city lonely and confused, getting on buses to try and get home though I didn't know where they were headed.

Somehow - I still to this day have no idea how - some friends caught up with me distressed and confused and drove me back to my parents' house in Devon.

After that I didn't really leave their house for 10 years.

Get help

For help with mental illness visit the Rethink, external or Mind, external websites.

My parents took me to see a psychiatrist who spoke kindly to me and put me on anti-psychotic drugs designed to lessen what are known as the "positive" symptoms of schizophrenia. These included the hallucinations, delusions and confusion I was experiencing.

It was actually really good for me to hear the diagnosis. Schizophrenia. At least then I knew what I was working with, I had an answer and could begin to move forward.

The medications helped almost straight away but what I really wanted to do was talk to somebody in therapy sessions. At the time there was a lack of funding for this type of treatment, something which continues to be a problem for people with mental illnesses today.

Alice struggled to talk for many years

With the medication, I began to make little steps towards recovery. I started talking a bit, and being able to wash and take basic care of myself. Anybody who says that a mental illness isn't disabling is wrong, it affected my whole body.

Unfortunately, the medication took a toll on my physical health and by the end of the following year I had gained around ten stone (63.5kg) in weight due to the side effects.

Weight had been a big problem for me during my school days, although looking back I realise I had nothing to worry about. So when I put on this weight it made it much more difficult. I felt unattractive, was reluctant to see my friends and I was still scared to go outside, so it was difficult to exercise.

After a few years I managed to find a job washing up in a local pub. I would put my earphones in and listen to music while I worked so I quite enjoyed it really. But unfortunately I had episodes of ill-health so wasn't able to sustain work long-term. Everything seemed to be a vicious circle.

Eventually, something miraculous happened and I made some friends. I had enjoyed art and music a lot before I became unwell and my mum persuaded me to join a local theatre group. I was scared at the prospect of meeting new people and acting on stage but everybody made me feel really welcome and I took a role in a play they were doing.

I was absolutely hopeless at remembering my lines but no-one seemed to care, and the others were so quick and funny that they were able to fill in whenever I forgot what I should be saying.

My best friend in the theatre group, Tristan, was very supportive, and I told him about my schizophrenia. He had experienced mental health problems too, so it was great for me to talk to somebody who understood. Eventually he announced that he was planning to go to university and, much to my surprise, he suggested that I apply too. I was terrified, but with his strength and encouragement and downright belief in me I applied and was surprised to be accepted at Chelsea College of Art.

My life began.

Schizophrenia: The Facts

One in 100 people in Britain have schizophrenia

It usually starts during early adulthood

The symptoms can be split into 'positive' and 'negative' symptoms. Positive symptoms include experiencing things that are not real (hallucinations) and having unusual beliefs (delusions) and negative symptoms include lack of motivation and becoming withdrawn. These symptoms are generally more long-lasting.

People with schizophrenia have an average life expectancy that is 15 years shorter than people without the condition.

Source: Rethink Mental Illness, external

I started making artwork in the form of photographs and films that expressed in some ways how I was feeling. I could communicate more through those mediums how I was feeling than I ever could in words. Another important step was that I was referred to a brilliant mental health team that helped me access the support I needed to become more independent. And the staff and students at the art college gave me all the support I needed.

Two years ago I had another small setback when my weight gain stopped me recovering properly from a chest infection and I spent 10 days in intensive care with bad asthma. Fortunately, I was well enough afterwards that I was allowed weight-loss surgery, another crucial step in my recovery.

Alice now

I started volunteering for a local mental health charity which helped me get more skills and experience. They pointed me towards some proper talking therapy which became instrumental in my recovery. Sadly, the organisation had a lot of its funding cut and the branch I was working in was closed, to much dismay from the staff and service users.

I was very lucky though. Before they closed, they helped me apply for an MA at the Royal College of Art and I began to take on some teaching work so that I could enable others to develop their own creative skills. I am now pursuing a PhD.

It has taken me 20 years to get this far in recovery, and I do still have setbacks. Schizophrenia is an extremely difficult condition to live with and I am lucky to have incredible support from family and friends who continue to step in and help me when I am unwell.

If we can challenge the stigma, get proper investment in mental health services, and show kindness and provide meaningful support to people who experience conditions like schizophrenia, then people will not be left as long as I was before they are able to make their own steps toward recovery.

Alice Evans is a filmmaker and photographer based in London. You can see her work here, external.

She was speaking to Kathleen Hawkins.

For more Disability News, follow BBC Ouch on Twitter, external and Facebook, external, and subscribe to the weekly podcast.