When disabled people took to the streets to change the law

- Published

In the 1990s hundreds of disabled people took to the streets in protest at the injustice they felt. Their efforts helped to bring about the Disability Discrimination Act which is 20 years old this week.

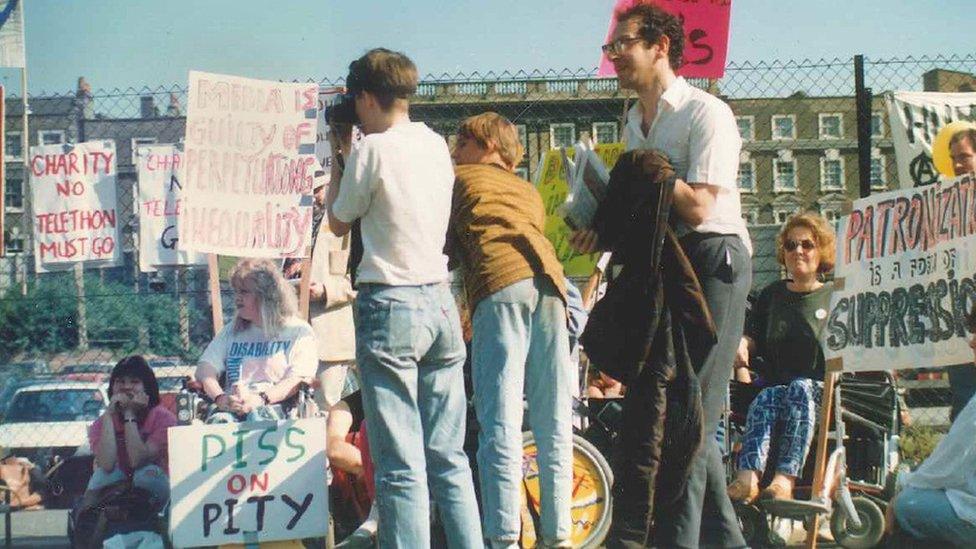

Disabled people chaining themselves to public transport, wheelchair users blocking streets, chanting loudly and being lifted from their chairs by police and laid down in the roads to stop them, protesters shouting out for civil rights - these were powerful images on the TV news in the early 90s, and a far cry from how disabled people were often represented (when they were represented at all), as passive and grateful recipients of charity.

In fact one of the movement's first big protests - in July 1992, was against ITV's 24-hour telethon fundraiser. The organisers were angry with what they said was a pitiful portrayal of disabled people on the programme and claim to have had 1,500 people out in support.

"We blocked the whole of Upper Ground outside the Telethon studios," says Barbara Lisicki, one of the heads of the Direct Action Network (DAN) for disabled people. "We had our own PA system, we had a party, we had musicians, we had a carnival on the street."

The protesters were also angry about the law which - until 1995 - allowed people to discriminate on grounds of disability.

"We brought people together who had had enough of not having any protection against discrimination," says Lisicki.

Twenty years of the DDA

"We had actions where young people got chucked out of a cinema because the manager decided that there were too many of them in wheelchairs. They'd been going there for two years, a new manager comes in and suddenly decides they're a fire risk.

"We had two wheelchair users who went into a cafe in Camden and got told to leave because their chairs were taking up too much space. We had a visually impaired woman from Peterborough who had a guide dog and used to go to her favourite Indian restaurant. A new manager came in and said that she wasn't allowed in with her dog. These were daily occurrences."

The protests inspired and motivated disabled people who realised they could exert pressure on lawmakers.

Adam Thomas suffered a spinal injury at the age of 17 in 1981. He says he was fortunate enough to have experienced life as a non-disabled person first but that being a wheelchair user was "much much harder".

He recalls how travelling by train was unpleasant and uncomfortable yet he still had to pay full fare.

"I'd have to give three days notice of travel and they would put me in the guard's van. You'd travel with the post, and people's bicycles and things. There was no heating in them often and often there was no light if you were travelling at night."

He met his wife-to-be, external, Agnes Fletcher, while chained up at a direct action protest. Fletcher went on to become a director at the Disability Rights Commission and is now a trustee for Scope.

"Adam and I have Barbara to thank for her handcuffs," says Fletcher. "[When we] met we were both handcuffed to different buses."

The 1995 change in the law made it illegal to discriminate on the grounds of disability in the workplace and also brought in some consumer protections, although it didn't immediately give access to transport. In addition it had a timetable for rollout on matters such as the built environment, education and transport - though this timetable stretched 25 years into the future which upset campaigners.

Disability equality trainer Phil Friend says: "On one level we all thought this was great, on another - we'll all be dead before we get on a train."

Find out more

Listen to Barbara Lisicki, Adam Thomas, Agnes Fletcher and Phil Friend discussing the 1990s protests on this month's talk show from Ouch. Download or listen to it here.

Fletcher says part of the problem was that many, including the government and some charities, did not view the barriers facing disabled people as discrimination. People viewed arguments about disability differently from those about sex and race, two areas in which discrimination was better understood: "It was all about unfortunate disabled people who of course couldn't work, didn't need to use transport and all those things. It was viewed in a very different way. And I think that's why it took so long because lawmakers and others didn't see it in the same way."

"What made me laugh is that often when we did actions the police arrested us and then they had to de-arrest us again because they didn't have any accessible vehicles to get us down to the cells in," says Lisicki. This basic lack of access ironically served to highlight the point the protestors were making.

Disability charities at the time were thought of as part of the problem by this new breed of campaigners. The "big six" charities were accused of wanting to maintain the status quo. but disabled people wanted more. Fletcher says they were lagging behind but DAN made them wake up. "They were a blocker at times in the 80s and in the early 90s," she says, but later they joined with grassroots groups and funded the Rights Now campaign which brought about mass lobbies of parliament.

The Disability Discrimination Act received its royal assent on 8 November 1995. In 2010 it was absorbed into new legislation, the Equality Act.

Friend says he isn't going to celebrate the anniversary of the act but sees it as a major turning point: "It's nice to remember the people that were involved at that time and what was going on that was so transformational - disabled people becoming organised and doing stuff which hadn't really been seen up to that point in '95."

Twenty years on, the battle is clearly not over for disability campaigners. Rights to independent living and social security are not part of discrimination legislation, although they are alluded to in the aims of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which the UK has signed up to. Moreover, budget cuts remain a key issue for many in the UK, with disability welfare now directed towards "those in most need".

On the other hand, disabled people can now turn up at a restaurant or a night club and expect to be welcomed, whereas they couldn't before 1995. They can also expect adaptations in the workplace and access to education. By 2020 the vast majority of train vehicles will have to be accessible by law - though the stations they pull into do not have to be.

The areas that the act covers have gradually broadened over the last two decades but the legislation didn't go as far as those early campaigners wanted. "Some people thought 'we've won with the Disability Discrimination Act'," says Lisicki. "We didn't win. It was never a victory. All that I ever say to people is that at least now the government agrees with us that discrimination happens."

For more Disability News, follow BBC Ouch on Twitter, external and Facebook, external, and subscribe to the weekly podcast.