'I went blind and feel partly to blame'

- Published

Leonie Watson lost her sight in her 20s after ignoring doctors' advice about her diabetes for years. Here she charts her journey into blindness, and the frustration of feeling partly to blame.

I became blind over the course of 12 months from late 1999 to the end of 2000. It was mostly my fault. I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when I was a little girl - the type where your body stops producing insulin. At the time they explained I would have to eat a precise amount of food each day, and that I would need to inject a precise amount of insulin to handle it.

When I was a little older I asked my paediatrician why it had to be this way, why I couldn't work out how much food I was about to eat, measure my blood glucose, and then calculate the insulin dose myself. To this day I don't know whether he actually did pat me on the head, or whether my subconscious has added a memory based on his reply ("don't be so ridiculous"), but it doesn't really matter in the scheme of things. That was the moment the rebellion started.

At some point during my teens I discovered I could skip an injection without anything terrible happening. I stopped monitoring my blood glucose levels almost entirely and when I was old enough to make my own decisions, I stopped going to the doctor for annual check-ups.

Throughout my student days I had a riot. I smoked, danced, partied, and kept on ignoring the fact I was diabetic.

What is diabetes?

Diabetes causes a person's blood sugar level to become too high

There are two main types - type 1 and type 2

In type 1 diabetes the body's immune system attacks and destroys the cells that produce insulin. This causes glucose levels to increase, which can seriously damage the body's organs

Type 2 diabetes is where the body doesn't produce enough insulin, or the body's cells don't react to insulin. It may be controlled by eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, and monitoring your blood glucose levels

Source: NHS Choices, external

By the time the century was drawing to a close, I was working in the tech industry as a web developer. This was the era of the dotcom boom and everyone was having fun. There were pool tables in the office, Nerf guns on every desk and many insane parties. Paul Oakenfold was the soundtrack to our lives, and we'd fall out of clubs at 6am and drive to Glastonbury Tor to watch the sunrise just for the hell of it.

One morning in October 1999 I woke up with a hangover. As I looked in the mirror I realised I could see a ribbon of blood in my line of sight. As I looked left then right, the ribbon moved sluggishly as though floating in dense liquid. Assuming it was a temporary result of the previous night's antics, I left it a couple of days before visiting an optician to get it checked. When I did the optician took one look at the backs of my eyes and referred me to the nearest eye hospital for further investigation.

When diabetes is uncontrolled for a time it causes a lot of unseen damage. When you eat something your blood sugar levels rise and your body produces insulin to convert that glucose into usable energy. If there isn't enough available insulin then the cells in your body are starved of energy, they begin to die and the excess glucose remains trapped in your bloodstream.

As if that wasn't enough, the glucose will then smother your red blood cells and prevent them from transporting oxygen efficiently around your body.

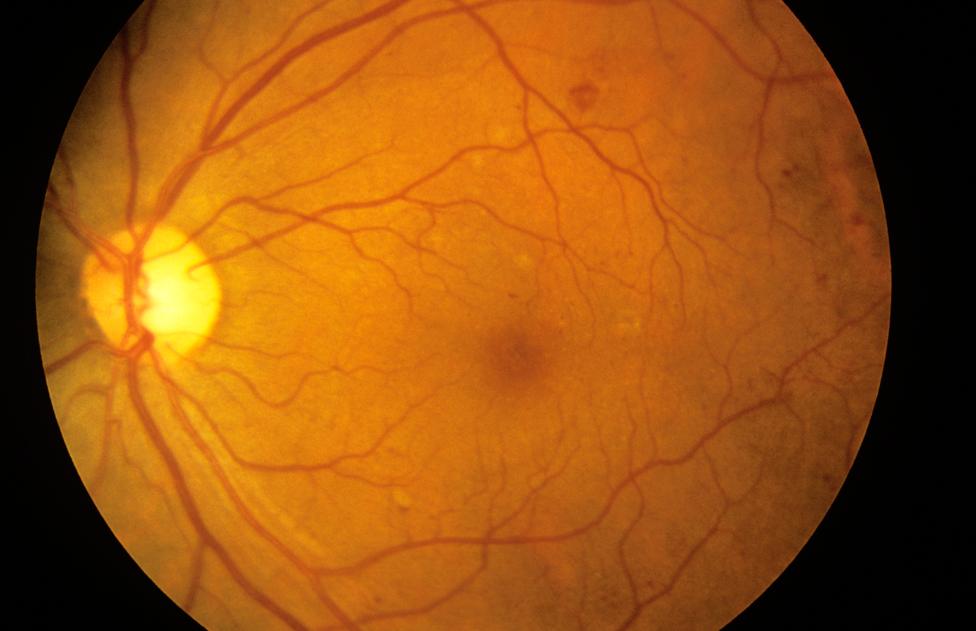

One of the ways this damage eventually manifests itself is diabetic retinopathy. In an attempt to get enough oxygen to the retina at the back of your eye, your body creates new blood vessels to try and compensate. The new blood vessels are created as an emergency measure and so they're weak. This means they're prone to bursting and haemorrhaging blood into the eye - creating visible ribbons of blood like the one I could see.

This all has the inevitable effect of damaging your sight.

The people at the eye hospital told me laser treatment might halt the breakdown of the blood vessels at the back of my eye and enable the remaining vessels to strengthen enough to get the oxygen to where it should go.

It wasn't pleasant. It requires an anaesthetic injection into the eye before a laser is repeatedly fired at the back. I remember one round of treatment skewing the sight in one eye by about 90 degrees - trust me when I tell you it's impossible to remain upright in that state.

Looking back, I realise that laser treatment was a futile gesture. No-one ever came straight out and told me the consequences of having advanced diabetic retinopathy, it was always spoken of in terms of a progressive deterioration.

I remember the day I admitted it to myself though. My sight had been steadily worsening and it was a day in the spring of 2000 that it happened. I was walking down the stairs at home when it hit me like the proverbial sledgehammer - I would be blind. With absolute certainty I knew I would lose my sight and that I only had myself to blame. I sat on the stairs and fell apart. I cried like a child. I cried for my lost sight, my broken dreams, my stupidity, for the books I would never read, for the faces I would forget, and for all the things I would never accomplish.

I reluctantly realised I needed help. My doctor prescribed anti-depressants that effectively put me to sleep 23 hours out of every 24. After six weeks I decided enough was enough and took myself off the meds for good.

A curious thing had happened in the intervening weeks though. While I was asleep my mind appeared to have wrapped itself around the enormity of what was happening. It wasn't in the form of a revelation or anything like that, but it was a recognition of what I was up against, and that was enough for the time being.

Over the ensuing months I gave up work as my sight continued to deteriorate.

I had days when I raged out of control and screamed or threw things at the people I loved just because they were there. There was the day I stumbled in the kitchen and up-ended a draining rack full of crockery that smashed into a thousand pieces around me. I remember once demolishing a keyboard I could no longer use, and kicking the hell out of the Hoover because the cable was so caught up around the furniture I couldn't untangle it. And there were those days, too numerous to count, when I bruised, cut, scratched or burned myself while doing everyday tasks, and the rage and the tears would overwhelm me all over again.

Towards the end of that year, not long before Christmas, the last of my sight vanished. When I think of it now, it seems that I went to bed one night aware of a slight red smudge at the farthest reaches of my vision (the standby light on the bedroom television), then woke the next morning to nothing at all.

Preventing diabetic retinopathy

To reduce your risk of developing retinopathy, it's important to control your blood sugar level, blood pressure and cholesterol level. Good control will prevent diabetic complications in almost everyone, according to the NHS. Other advice includes:

Attend annual screening appointments

Inform your GP immediately if you notice any changes to your vision

Take medication as prescribed

Lose weight (if you're overweight) and eating a healthy, balanced diet

Exercise regularly

Give up smoking

Only 3% of blind people are completely blind. Most have some degree of light perception or a little usable vision, but I'm one of the few who can see nothing at all, and nothing is the best way to describe it. People assume it must be like closing your eyes or being in a dark room, but it's not like that at all. It's a complete absence of light, it isn't black or any other colour I can describe.

Instead my mind gives me things to look at. It shows me a shadowy representation of what it thinks I should see - like my hands holding a cup of tea. Since my mind is constrained only by my imagination, it rather charmingly overlays everything with millions of tiny sparkles of light, that vary in brightness and intensity depending on my emotional state.

My retinas are long since gone, so no actual light makes its way to the back of my eyes. This is what gives my eyes their peculiar look - each pupil is permanently open to its fullest extent because they are trying to take in light. And oddly, it's the appearance of my eyes which still makes me feel a little uncertain about being blind, but given that I no longer really remember what I look like, perhaps there will come a time when that will fade and leave no uncertainties. I'm pretty well-adjusted to being blind.

Leonie, pictured with her fiance Dan

With the last of my sight gone, things actually started to get a lot easier to deal with. I stopped trying to look at what I was doing, and started to use my other senses.

Let me clear up a common misconception while I'm here, I do not have extraordinary hearing or sense of smell. I do pay more attention to those other senses though. For instance, I'll often hear a phone ringing when other people don't because I'm devoting more of my concentration to listening than they are.

The next few months were a time of discovery, sometimes painful, often frustrating, but also littered with good memories. I learned how to do chores, how to cook, where to find audiobooks, how to cross the road, and what it feels like to drink too much when you can't see straight to begin with.

It's been 15 years since all this happened. Somewhere along the way I went back to work, and I now have the uncommonly good fortune to be working and collaborating with lots of smart and interesting people, many of whom I'm delighted to call friends.

So life moved on, as life has a habit of doing. I celebrated my 40th birthday last year - perhaps that is what has given me cause to reflect and share my story.

Personal photographs provided by Leonie Watson, who originally told the story on her personal website , external

For more Disability News, follow BBC Ouch on Twitter, external and Facebook, external, and subscribe to the weekly podcast.