Africa's disability innovators

- Published

People in Africa have been finding new solutions and approaches to improve the quality of life for disabled people on the continent

Fighting for disability rights in Africa is a huge task but some people are taking it upon themselves to make a positive change.

The World Health Organization estimates that at least 81 million people across Africa are affected by some form of disability.

As a result many grassroots activists, academics and artists are finding innovative ways to improve accessibility for people with disabilities, at both a local and international level.

From the Accessible Guidebook to Ethiopia, to wheelchairs made especially for rough rural terrain, there are numerous examples of resourcefulness and audacity.

BBC Africa spoke to eight of these change-makers - to find out what they are doing and why they were inspired to make a change.

Nigeria: The singing activist

Grace Jerry recently met President Obama

In 2002, singer Grace Jerry, external was on her way home from choir rehearsal when she was knocked down by a drunk driver and left with paralysis of the lower limbs. After the accident she says music took on a whole new dimension: "Today, it is more than just holding the microphone, it is my world, my platform and my voice." Last year, she introduced President Obama at the Mandela Washington Fellowship Young African Leaders Initiative programme in the United States. "I had to hold back the tears when he walked up to me on stage and said some beautiful things about me and the work we are doing in Nigeria through [disability advocacy NGO] Inclusive Friends," she remembers.

Ethiopia: The accessible guidebook

The Ethiopian Center for Disability and Development

Four years ago, the Ethiopian Center for Disability and Development published its Guide to Accessible Addis Ababa, reviewing the accessibility of different hotels, government buildings, restaurants and public spaces. "When we saw that it was really helpful for visitors as well as locals with disabilities, we thought 'Ok we have to scale up this project'," says programme director Retta Getachew. "We have six guides now and another that combines them all in one book, which is the Guide to Accessible Ethiopia."

South Africa: The artist turned biomedical engineer

When her daughter was born with disabilities, Shona McDonald, external says medical staff told her: "'Put her in a home, have another kid and move on' - that there was nothing that would really add value for her. And it was through my frustration and anger that I decided I wanted to prove them wrong." Using her sculpting skills, she started designing mobility equipment and supports - with the help of the University of Cape Town's biomedical-engineering department. Now her company, Shonaquip, manufacturers everything from wheelchairs to posture supports, which can be easily assembled, fitted and maintained by local therapists and technicians all over Africa.

Lesotho: The alternative beauty queen

Tlhokomelo Elena Sabole

Last year, Tlhokomelo Elena Sabole, external was crowned Miss Deaf Africa 2015. It was, she says, a dream come true: "Winning was so amazing. I have never been happy like that." Growing up in Lesotho as a deaf person is not easy, she says. But she hopes to change attitudes towards non-hearing people, and wants to see access to information opened up - such as through sign language on TV and signing classes in schools. "My dream is to have my own business," she says, "for example a salon where I can share my skills and work with other deaf girls."

Zambia: The low-cost mobility aids

When Kenneth Habaalu joined the APTERS organisation they were finding it difficult to identify children with disabilities in the community. "People didn't want others to know they had a disabled child at home," he explains. "One mother told me she usually leaves her child in bed when she goes to the market. To help her sit, she said: 'I dig a hole outside the house and put the child in there.' To stand, she would tie the child to the tree with material. I think it's inhuman to do such things." With limited resources, APTERS' team of eight (all of whom are disabled) use recycled paper and cardboard to make papier maché chairs, standing frames and walking aids, as well as teaching blocks for physiotherapy.

Uganda: The Braille production unit

Victor Locoro has been working as a lecturer in the Faculty of Special Needs and Rehabilitation at Uganda's Kyambogo University for 20 years. As well as offering courses in community-based rehabilitation and disability studies, the faculty has its own Braille Production Unit. "At the moment it's on hold because one of the embosser machines needs serious repair," says Mr Locoro, who lost his sight at the age of ten. "But we are able to produce small amounts of material for the students, and are in the process of replacing the machine so that we resume full production. This includes producing books in Braille for primary and secondary schools; ministries of education, science, technology and sports; as well as civil society organisations."

South Africa: The deaf rugby pioneer

In September 2007, Tim Stones co-founded the South African Deaf Rugby Union (SADRU). But there was a problem, the union wasn't affiliated with the South African Rugby Union - and so wasn't recognised by World Rugby. That all changed in 2014, and the following August SADRU held its first official Deaf Rugby Test series - the first of its kind held on South African soil - against Deaf Rugby World Champions, Wales.

Today, the union has around 90 deaf players. "However our numbers are steadily growing," says Mr Stones, "especially now that we are forming provincial Deaf Rugby unions in each province of SA." SADRU is also working with audiologists to conduct screenings in clubs and schools, to identity potential players - and undiagnosed hearing problems.

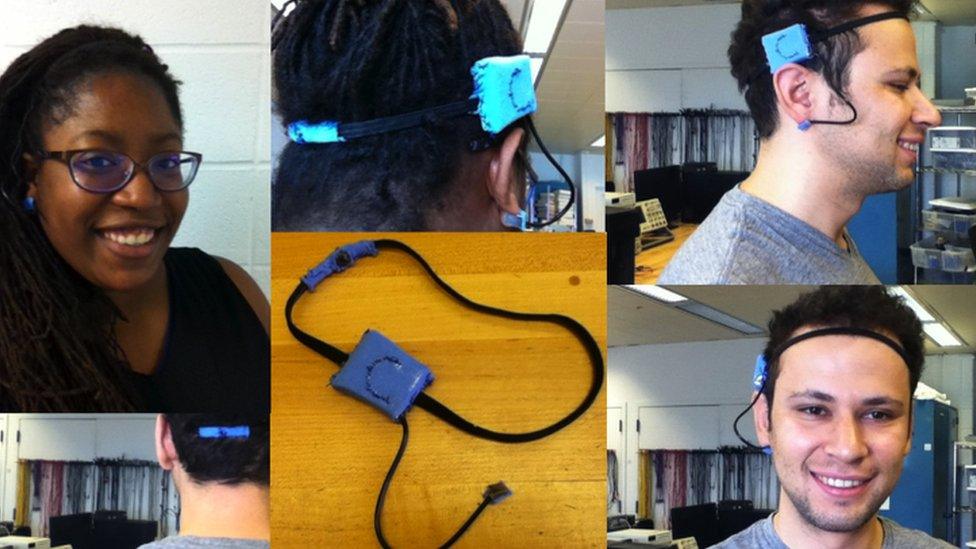

United States: The brain-powered game controller

In between studying for her Electrical Engineering Masters at Colombia, Kay Igwe, who was raised in America but whose parents are from Nigeria, has been busy making an accessible computer game that's powered by brain waves. "A lot of people are investing in gaming culture right now," she explains, "but when someone has a neurodegenerative disease that impairs them from using any of their limbs or eye movements - or if they've suffered from a stroke or something that has left them paralysed - they cannot use a controller in the same way that someone who has those abilities can." Her solution? To use electroencephalogram or EEG signals to connect the brain to a computer game, so that a person can control a player using their brain waves.

This is part of BBC Africa's Living With Disability season. Find out more here, external.