Scribble sanctuary: The artist who tackled mental health difficulties by sketching

- Published

For Ruby Elliot her sketchbook was her only sanctuary from a life in "constant crisis mode".

"I recovered from anorexia, I became bulimic and struggled with self-harm and depression and I was diagnosed with bipolar after that," says Ruby, who is now 22.

The illustrator and author, now known as Ruby etc, found herself in a cycle of hospitalisation from the age of 14, and she found each return to the classroom painfully stressful.

"I was too unwell for school a lot of the time and hated formal art classes in particular," she says, and night-school was a non-starter too.

Ruby is now building a successful career in art and has landed a publishing deal.

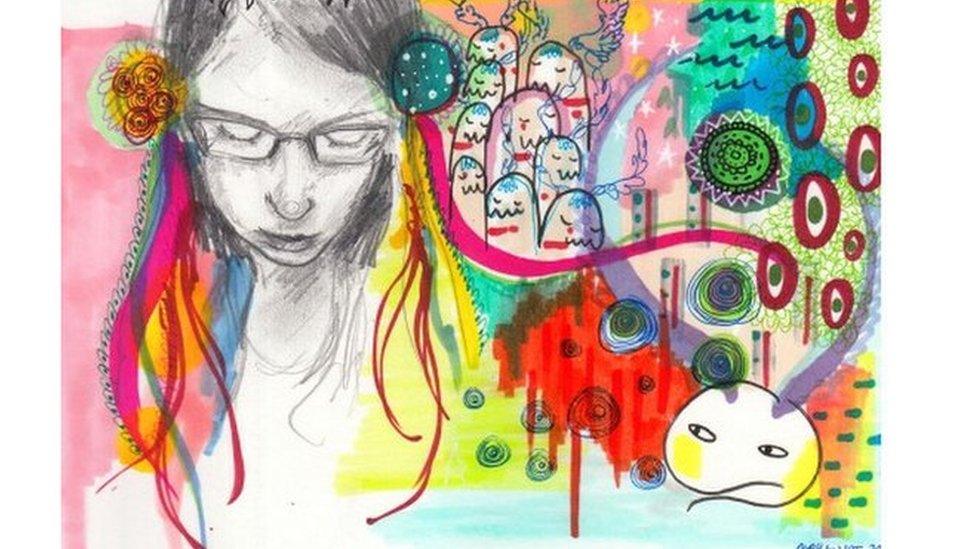

'God there is so much' relates to the knotted notion of feelings

At 17 she left education and began to draw every day. At the time, it was one of the only things she could engage with and it became an important coping mechanism.

"When I drew it was a relief. It was catharsis," she says.

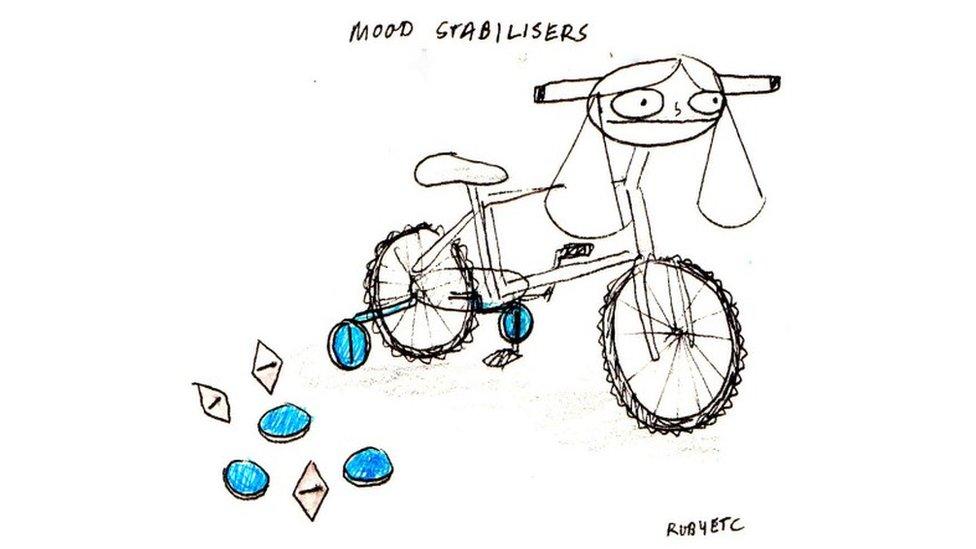

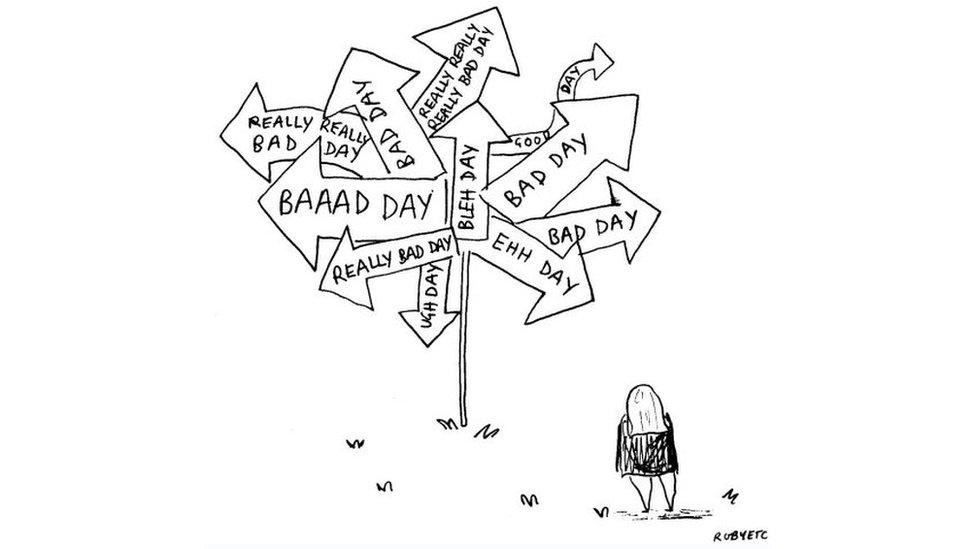

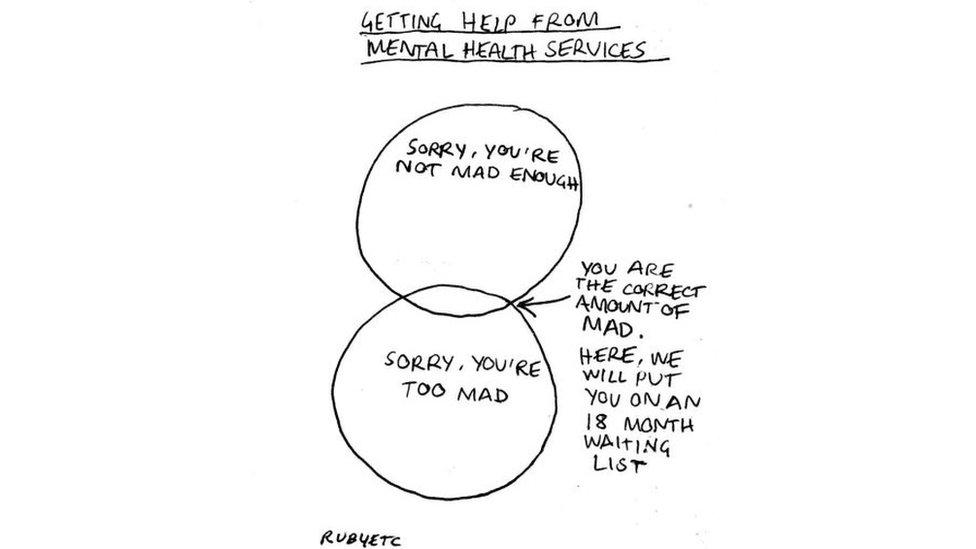

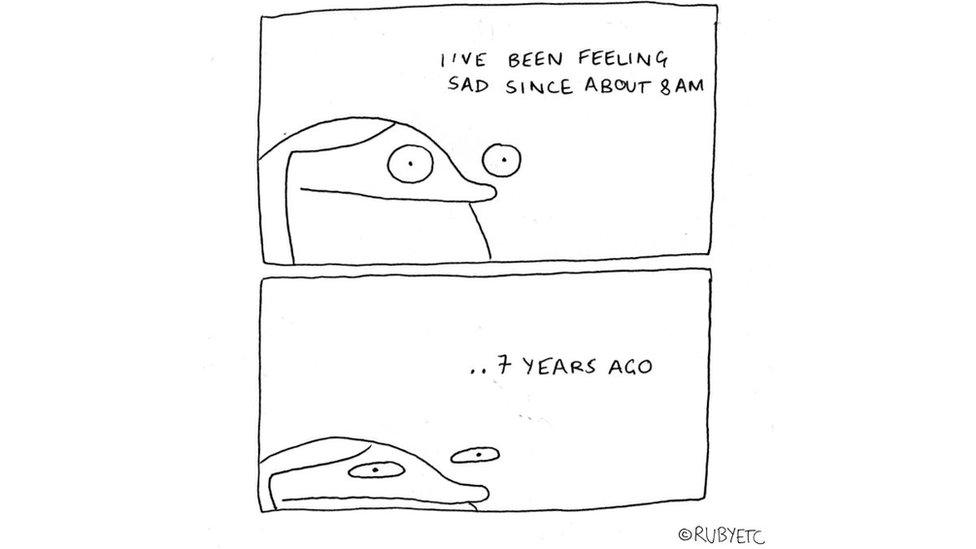

Her sketches started on post-it-sized bits of paper always with the aim of making herself laugh. The "bizarre" nature of the mental health system provided plenty of inspiration - from the therapists to the mood stabilisers, which she thought of as bike stabilisers that required her to "do the peddlin'".

"Often when I'm feeling really down I'll draw very silly things to take my mind off it all. Other times I might be feeling okay, but want to focus on something a little deeper or more serious," she says.

After encouragement from a friend, Elliot started to post her images online. Over the next three years she amassed 200,000 subscribers to her Tumblr blog, 31,000 fans on Facebook and 28,000 Instagram followers.

"I was so unwell and isolated but being able to put stuff on the internet and communicate with other people is something I could do from inside the house when I couldn't leave due to paranoia."

Elliot now takes her sketchpad everywhere she goes and regards it as her "safety blanket". She doesn't do draft versions of her work, she just goes straight to it in pen - generally in black ink.

Ruby Elliot's bipolar episodes

Being depressed for me feels like I've been steam-rollered by an external force that renders me a grotty non-human pancake of sadness. I become so saturated and overwhelmed with feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness that the simplest of things become a giant effort - it can take me a week or more to convince myself to crawl into the shower. The subsequent shame and embarrassment about not being able to Do Anything is the icing on the cake really. I become noticeably slower. I sleep more. It's a scary place to be.

The other side - mania - or hypomania (mania but without psychotic symptoms) is like a switch flicks within me and I suddenly have masses of energy; I sleep less, I do more. I can seem quite happy and 'well'. But I will have a pretty constant stream of rushing thoughts I'm trying to manage, and although they can be exciting, when I get sleep deprived I get agitated. It can get to a point where I can't 'switch off' and that gets quite dangerous and destructive.

In the early days she had to deal with being "hypercritical" of herself and describes her sketchpad as one of the only places she didn't judge herself, saying: "It's like a separate mental space."

The healing power of art has now been formally recognised. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence recommends art therapy as a cost-effective way of helping people with depression.

Cal Strode from the Mental Health Foundation says it offers "expression when the emotional issues we're experiencing are too confusing or distressing to communicate with words".

He says focussing on an activity calms the mind, "occupying and holding it in the present moment where it can't dwell on the past or worry about the future".

His father, Liverpool artist Steve Strode, says he too has witnessed the power of art when he worked with another group which often finds itself isolated - inmates at a prison.

"Although people wouldn't openly talk about feelings or emotions to keep up a front, often these things would come through in their art," he says. "People in my classes would sit and meditatively paint from photographs of family members for hours.

"It was their escape."

For Elliot, that freedom has culminated in a book-deal which caused a five-way bidding war, for a collection of drawings and personal essays about her experiences.

"It was emotional digging things up and feeling them all over again, and battling with 'I'm not good enough' while trying to put this thing together and look after my health at the same time. But luckily I can sit at home and draw stuff at my desk if I don't want to go out. It has been stressful but very exciting."

Elliot says she aimed to write and draw about mental health in the context of the person rather than "the stuff" which goes with it. "I'm quite interested in bridging that polarising gap between illness and wellness - it's the question of degree and extent," she says.

Her book It's All Absolutely Fine is an irreverent look at mental health issues from anxiety to eating disorders and alienation.

Committing to the book project was a practice in managing her own condition and she was strict at giving herself time out. Sometimes she would work for a couple of hours, other days just 10 minutes, and she was also aware of how much social media influenced her productivity and motivation.

"I learned that I didn't have to post everything and I tend to steer clear of a lot of the negative stuff, but the positive response is a really great driving force," she says. "I've never made it my prerogative to help people, but I'm touched and humbled when people say it's helped them."

Elliot who works at "an incredibly messy desk" at her parents' house in London or in cafes "without the distraction of computers" said balancing her sanctuary against her new-found job was crucial when it has been so instrumental in her recovery.

"I still struggle with mood episodes so I try and retain as much of the enjoyment as I can with drawing - but it can be stressful knowing you've got to produce work," she says.

"The best work happens when I'm enjoying it; because if you're playing to the audience too much, or worrying about how popular it'll be, it always ends up being less funny, less 'you'."

Ruby's story and pictures can be seen in her book It's All Absolutely Fine.

- Published29 September 2016

- Published18 February 2016

- Published19 January 2013