The man diagnosed with pathological laughter

- Published

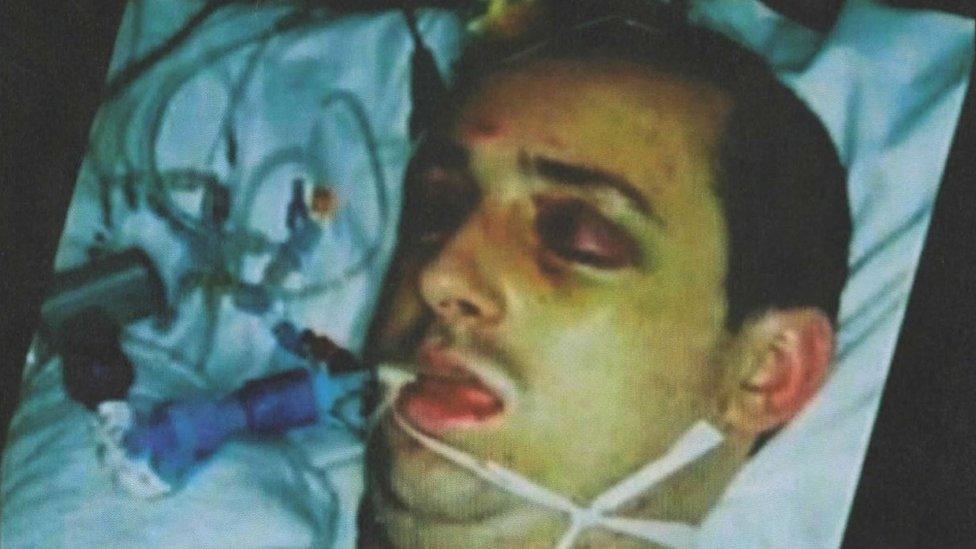

Paul Pugh was in the most critical meeting of his life. He was being told what his future would be like after receiving a brain injury in a brutal assault. He laughed the whole way through the discussion but, to him, it felt like he was sobbing. He would later be diagnosed with pathological laughter.

Pugh, now 38, had been on a night out with his Cwmaman Football Club teammates in January 2007 when he was targeted in an unprovoked attack on a cold January night.

As he left a pub in his home town of Ammanford in Carmarthenshire, west Wales, four men he didn't know rounded on him and repeatedly punched and kicked him.

Pugh's skull was fractured and he fell into a coma for more than two months. A blood clot which measured 10cm x 4cm formed on his brain and he was left with slurred speech, chronic fatigue and mobility difficulties which resulted in him having to use a wheelchair.

"I've had to learn to walk and talk again and come to terms with the fact that I will never fully recover," he says. "Life has been a struggle for me and my family, but we're ploughing through it."

Pugh spent 13 months in hospital, but it wasn't until month four that he had his first laughing fit.

"It was a serious meeting with my consultant, rehabilitation therapists and my family to discuss what my life and future was going to be like," he says.

"When they started talking about me, I was frightened and it triggered something off in my brain and I laughed right through the meeting.

"I was actually crying my eyes out, but it came out on the surface as laughter."

At first, no one understood his behaviour, his family even thought he was "making a scene in public, pleading for attention".

It took several years before Pugh's fits of "full on laughter" were diagnosed as pathological laughter or the Pseudobulbar Affect (PBA).

The condition arises when there is a disconnect between the frontal lobe of the brain - which keeps emotions in check - and the cerebellum and brain stem - which regulate the expression of emotion. It's a real crossed-wires moment.

PBA can affect those with neurological conditions or injuries such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, or Alzheimer's disease.

Andy Tyerman, consultant clinical neuropsychologist of brain injury charity Headway, says: "The term refers to uncontrolled expression of emotion that is disproportionate or inappropriate to the social context and may be inconsistent with what the person is actually feeling.

"A person might also appear very distressed about something that would previously have been only slightly upsetting."

In Pugh's case, he laughed when he thought he was crying.

"I know when I'm laughing or crying, but other people don't," he says. "Some have been upset and reacted by being sarcastic with me or even aggressive and try to hurt my feelings because they think I'm laughing at them.

"It's amazing how important laughing is. You take it for granted but it has a really powerful effect, if you share a joke with someone it's special."

Pugh says his family are very understanding. His mum has become his full-time carer to help with his mobility issues, his dad, aged 72, still works and his brothers - Simon and Matthew - have both had a hand in helping him over the past decade.

He says the diagnosis "hit me hard" and sometimes attracts unwanted attention but he can now sense when an episode is imminent.

"I feel a laugh coming a few seconds before it happens - sometimes I can control it but a blip can happen. The laugh doesn't last long, a minute at the most, but it can cause a lot of problems if people don't understand."

Pugh has developed his own method to avert an episode by "thinking of something or someone bad without giving it feeling" and estimates he can control nine out of 10 laughing fits.

It's been an "extremely tough 10 years" since the assault, he says.

He had to give up work as an electrician and now spends his time in therapy or visiting the charity Headway Carmarthenshire which, he says, gave him an "insight of being with people with brain injury" and reassurance he wasn't on his own.

"Since the incident we've met the most incredible people you'll ever meet, all wanting to help me," he says. "On the other side of the dice, I feel like I'm under house arrest because the injury affected my mobility and balance, therefore I need assistance whenever I go outdoors."

In 2014, Pugh started Paul's Pledge - a campaign to educate people about alcohol-fuelled violence which Dyfed-Powys Police is also involved in.

He makes visits to schools, colleges and youth clubs and has had an "absolutely fantastic" response because "they can see that it's real and not theatrical".

"This is my life now - I've moved on from what happened," he says. "There are many things I can't do - but this [campaign] I can do. I think it sends a powerful message to the world. I don't want to see anyone, nobody in the situation it left me and my family in."

The four men responsible for Pugh's attack were jailed for between nine months and four years.

Pugh says: "The one that kicked me in the head with full force from point blank range, almost killing me, was let out. What about me? Ten years later, I'm still serving my sentence."

For more Disability News, follow on Twitter, external and Facebook, external, and subscribe to the weekly podcast.

Related topics

- Published6 January 2017

- Published6 January 2017