The family who broke records and changed laws

- Published

Deborah McFadden was top of her class when she was paralysed from the neck down by a rare illness. For the first time, she knew what it was like to be discriminated against. It would later motivate her to challenge the US legal system for the two disabled orphans she adopted from Russia and Albania.

This is the extraordinary story of a woman who caught the attention of a US president, and the siblings who went on to break world records.

Deborah was a straight-A student and competitive fencer when she started to feel exhausted. Doctors diagnosed her with Guillain-Barré syndrome, which crept through her body. Her immune system attacked her nerves and destroyed any sense of feeling.

"It starts at your feet and it works its way up and you can't stop it," she says. It's loss of sensation and then no movement. I couldn't move my arms. I had to be fed and dressed.

"The hospital called my parents and said, 'She may die you'd better get here. If she doesn't die, she'll never walk.'"

Deborah stabilised but remained paralysed. She used an electric wheelchair to get around. She hated the inactivity and decided to return to school, because "the only thing I could do was talk". But back in class, she found people treated her differently.

"I drooled and needed help doing things. But [people] spoke louder to me. They treated me like an idiot, Why would they do this?

"There were people who stayed with me that surprised me. I was also surprised at those who just couldn't handle it."

President George H W Bush

Employment was tough, too. People didn't see her potential. She was offered a job in a call centre because she could dial numbers using a stick attached to a baseball cap.

Slowly, over 12 years, she learned to walk again - but it didn't erase the feeling of marginalisation.

"I witnessed first-hand discrimination, so I was very active politically, wanting to change the system."

Her campaign caught the attention of President George H W Bush. He appointed her United States commissioner of disabilities - and she helped write the Americans with Disabilities Act.

That was 1989.

Unknown to her, that same year, a baby born with spina bifida - a deformity of the spine - had been handed into an orphanage in St Petersburg, Russia.

St Petersburg, Russia

Nina Polevikova, the child's mother, had been advised it was the best thing for baby Tatyana, as she might receive some medical treatment. She gave her daughter to Orphanage Three, a place which would become the girl's home for six years.

"I had no medical treatment, I had no wheelchair, no education," says Tatyana, who is now 29.

"You wake up, and just follow the same routine. I scooted around or I walked on my hands."

Communism had started to collapse and Deborah was tasked with distributing US aid. A visit to Orphanage Three was arranged. By now it was 1994.

She was led around the home and noticed a "little girl with a bow in her hair bigger than her head". The girl was being kept in a separate room because of her disability.

"She just had these bright eyes and this great smile. I said, 'Come on in.'"

Listen to the BBC Ouch podcast series with Tatyana and Deborah McFadden about their extraordinary lives.

Part one: From Russian orphan to Team USA and part two: Turning to snow to find my mother

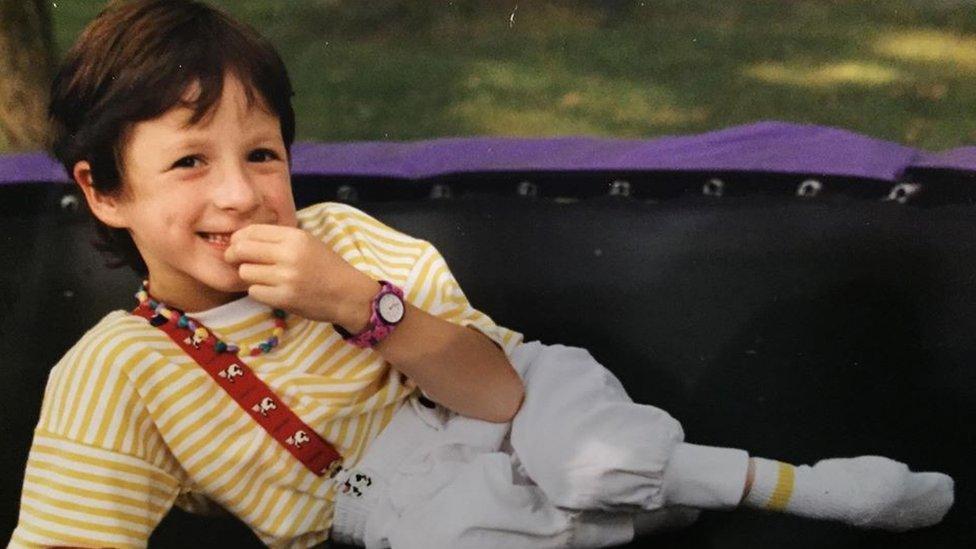

Tatyana as a child

They sat together. Deborah talked in English - Tatyana in Russian - but they understood each other in other ways.

"That night when I was back at the hotel I could not get her off my mind," Deborah says. "And so I told the staff 'I'm going to go back to that orphanage.'"

She returned every six weeks armed with clothes, toys and a wheelchair. In return the orphanage placed a photo of Deborah in the girl's room.

Tatyana told everyone the woman in the picture was her mother.

During another visit in 1995 Deborah was told Tatyana was due to be transferred to a home for disabled children. It was time to say goodbye.

"It had never been on my mind to adopt, but the moment they said they were going to transfer her to this place that, frankly in your worst nightmare you can't imagine, I said, 'You can't do this.'

"The reaction I had was a reaction of a parent."

Deborah called her partner Bridgette in Baltimore, who was already well aware of the girl who Deborah "talked non-stop about". Bridgette agreed they should adopt.

Twelve months later Tatyana arrived in the US.

Tatyana as a child

"It was really exciting, but scary," Tatyana says. "I had a lot of first things happen - surgeries, going to a friend's house or going to school. I even tried ice cream for the first time and I remember telling my parents to put it in the microwave."

Behind the excitement, Deborah had sobering news. Doctors had said due to a lack of medical attention, Tatyana wouldn't have a long life. A couple of years, maybe.

"I thought I've got to get her strong. I thought swimming - you don't need your legs."

They tried the local pool, but every instructor turned them away until Deborah offered to pay over-the-odds privately.

After Tatyana pushed herself into the water and resurfaced she shouted "Ya sama!" - Russian for "yes, I can do this". It started her love of sport.

She joined a club for children with physical disabilities and tried different sports.

"There was just something with wheelchair racing that really clicked with me," Tatyana says.

"I'm not sure if it's the need for speed as a child but it was just something I really loved - and it allowed me to become stronger and more independent."

As Olympic-fever hit America ahead of Athens 2004, teenage-Tatyana read about the selection competitions for Team USA and declared she wanted to become an Olympian. She had never heard of the Paralympics.

She showed promise on the track so her parents found the nearest para trials. Tatyana was 15-years-old and the youngest competitor.

Tatyana and Deborah

Against the odds she qualified for the 100m, 200m and 400m and was told "go for the experience".

She returned with a silver and bronze.

"It was absolutely amazing," she says. "When I was on the medal stand I was already thinking about the Beijing Games and I wanted to become faster and better."

Tatyana returned home on a high with plans to join her high school's track team.

But she got a shock. The school told her that due to health and safety reasons, she couldn't use the same track as her friends or join the club.

The topic went back and forth between school and family until Deborah made a demand.

"You give her a uniform and you let her run around the track. They said, 'Sue us'."

The McFaddens did. They filed for no damages - they wanted equal opportunity not compensation. They won their county case - and then a similar battle with the state of Maryland.

But nationally, disabled students across the US were not guaranteed the same opportunities as Tatyana.

This irked the young athlete. It seemed short-sighted. So she asked her mother to make it law.

Hannah and Tatyana competing together at London 2012

"I said, 'You're killing me Tatyana, this is a lot of work,'" says Deborah - but they managed to get the Sports and Fitness Equity Act, also known as Tatyana's Law, passed and put into federal law. It enabled those with a disability to participate in school sports.

But Tatyana says the battle to get to that point wasn't pleasant.

"Every track meet that I went to they were always booing. But on the inside I just knew this was the right thing to do."

During the highs and lows the McFadden family had expanded. Hannah was adopted from Albania and Ruthie joined the family too.

Hannah, who has an above-knee amputation due to a bone deformity in her left leg, also took to wheelchair racing and won a place on Team USA alongside her sister.

The McFaddens became the first ever siblings to compete at the same Paralmypic Games when they raced at London 2012.

Ruthie, who is able-bodied, is described as the creative one.

"What I saw in them was their spunk," Deborah says of the deprived children she helped shape into extraordinary people.

Tatyana has shown her determination and stamina time and again.

Tatyana with Prince Harry

In 2013, she won all the major marathons - London, Boston, Chicago and New York. She repeated the feat in 2014, 2015 and 2016. Something no able-bodied or para-athlete has ever achieved.

But she was tempted by a new challenge in 2014, which would take her to her birth country - the Winter Paralympics in Sochi, Russia.

The problem was, Tatyana didn't do winter sports. She considered the options and settled on cross-country skiing.

"It takes a lot of endurance, strength and technique and I had two out of the three," she says.

But this time it wasn't just about the sport.

In 2011 Deborah had tracked down Nina, Tatyana's birth mother, and she and Tatyana had met.

Tatyana with her adopted mother Deborah McFadden and her birth mother Nina Polevikova

"I was almost emotionless because I didn't really expect anything in case she didn't want to meet me," Tatyana says.

"I think she was overwhelmed and kind of relieved too. She had to do the hardest part - give up a child in the hope of a better life - and I have a great life so I'm so grateful for her."

They kept in touch with "casual emails", using Google translate, as Tatyana fought for a place on Team USA's winter squad.

"It was always a dream of mine to have my birth family and my adopted family at one competition," she says. "So I thought why not, dreams are never too big."

But she had a reality check. She was used to being on the podium, but now "you had to turn the last page to see my results" and her fellow competitors weren't always supportive.

"I had people making comments like, 'You should just go back to your summer sport, why are you even trying?'

"It came to a point where I didn't think I was going to make the team."

Tatyana competes during the Women's 12 km Cross-Country Ski Sitting at the Sochi Olympics

It took a final sprint in the last competition for Tatyana to secure her place. The underdog once again, she claimed silver in front of her American and Russian family which she describes as "the cherry on top".

Tatyana continues to rack up the medals. In the past few weeks she won the Boston Marathon and came second in the London Marathon.

She's also involved in the Toyota Mobility Unlimited Challenge - a competition to improve mobility options for those with lower-limb paralysis.

Some inventors have suggested installing phone chargers in wheelchairs - while Tatyana wants a lightweight, foldable, wheelchair she can "whip out" on aeroplanes. "I've missed so many connections waiting for the aisle chair assistance and that's just not OK," she says.

The winner will be announced in 2020, the same year the Tokyo Paralympic Games take place. A date firmly fixed in the McFadden diary.

"Training's going pretty well and so I have big goals in mind, but that's what it's about," says Tatyana.

For more Disability News, follow on Twitter, external and Facebook, external, and subscribe to the weekly podcast.

Related topics

- Published27 April 2018

- Published11 May 2018

- Attribution

- Published14 March 2014