Transcript: Life in the dark shadow of Mini-Me

- Published

This is a full transcript of the Ouch Talk Show: Life in the dark shadow of Mini-Me as first broadcast on 4 May and presented by Kate Monaghan and Simon Minty

[Jingle: Ouch]

SIMON - We're back. It's the Ouch disability talk show. I'm Simon Minty.

KATE - And I'm Kate Monaghan.

SIMON - It's May, summer is around the corner, although that may be less welcome if you're at school or college and have to sit exams, the ones you've been dreading.

KATE - Oh, I hated my exams, didn't you?

SIMON - Yeah. It's been a while though.

KATE - Yeah. We'll be looking at the effect exams can have on people's mental health, and we're not just talking about the students taking the exams, but also the teachers, the ones putting them through it. We'll be talking to someone who worked as a maths teacher. Oh… But hey, let's not judge her too soon, 'cause in fact it turns out she's actually a human being. Who knew? And here she is, Lucy Rycroft-Smith. Hello Lucy.

LUCY - Hello.

KATE - How are you?

LUCY - Okay, thank you.

KATE - Good. Now, the stress of the job took such a toll on her mental health that she left, and she has news for anyone who's ever struggled with maths. She says that your maths anxiety might actually be something you've picked up from your teacher. More on that later. And for anyone who's not taking exams or helping friends and family through them we've got stuff for you too.

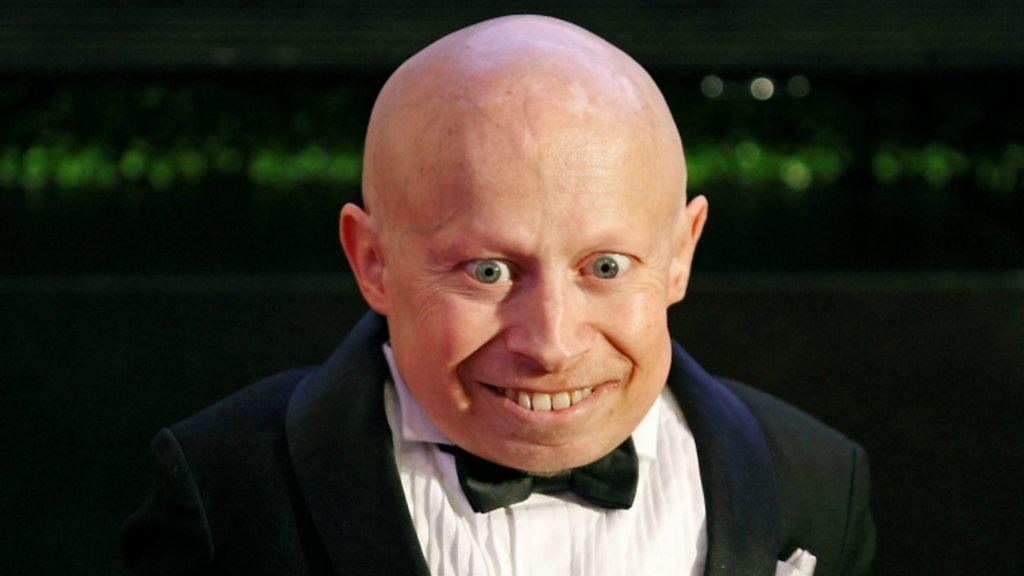

SIMON - We'll be talking about Verne Troyer who was Mini-Me in the 'Austin Powers' films, and who died in April. Characters like Mini-Me might be funny to some, but we've got someone in the studio with us who says that showing somebody with dwarfism in that light onscreen made his life a complete misery. Hi there, Eugene Grant.

EUGENE- Hello.

KATE - We also have Liz Atkin in the house. Hello Liz.

LIZ - Hello.

KATE - Liz is an artist with, now give me a second to say this, dermatillomania. Dermatillomania?

LIZ - Dermatillomania, or compulsive skin picking.

KATE - Okay. So that's skin picking disorder.

LIZ - Yes.

KATE - Okay. To you and me. Well, not you, because you know it as dermatillomania I guess.

LIZ - I know it as many things. [laughs]

KATE - Now you've just got back from a skin picking and hair pulling conference in the United States.

LIZ - I have, yes.

KATE - Was it great?

LIZ - It was. It was everything you can imagine. Yes, I've returned from the TLS Foundation Conference, it's the only one of its kind at the moment in the world for these conditions.

KATE - Great. Well, we're looking forward to hearing a lot more about that later.

SIMON - There are short person conventions and so on, which I thought was quite niche, but yours is very… I mean, how many people go?

LIZ - Five hundred, and the leading kind of scientists from around the world present their latest research into these conditions, so it's quite an important event for those of us that have the disorders.

KATE - Aren't you off to a short persons' event, Simon?

SIMON - You're looking at an athlete. [laughter] Whoa, whoa, whoa, what's with that laughter? So yes, I'll be going to the National Dwarf Games which are coming up soon, three days of different sports and activities, and I'm doing the marksmanship.

KATE - Right. Can I ask an awkward question?

SIMON - Oh… Yes, you can.

KATE - Now, I don't know that you are totally known for any like, athletics…

SIMON - Athletic prowess?

KATE - Yeah, marksmanship or not.

SIMON - Yeah.

KATE - Is this one of those like oh, it's a games, you're all dwarfs, therefore you can all just come along, have a go?

SIMON - [inhales]

KATE - You know, all of that kind of thing? Or is it like a real event?

EUGENE- That's outrageous.

SIMON - Yeah, thanks Eugene. This is the perennial debate actually. And even actually after the games there's a summit, an international, because this is world now, there's loads of different associations. And always the conversation is, how much is about elite athletes? Because this is the highest level we can go before you go into the Paralympics.

KATE - Okay.

SIMON - Or, how much is just, rock up, enjoy? The bit they do, if you're going you must get involved. You can't just go and spectate, you must practice, you can't just turn up if you've never done it before. So they've got some rules in there, but inevitably for some people this is quite new and there are others who are really dedicated, they're spending a lot of time practising.

KATE - Yeah. But which are you? [laughter]

SIMON - I have spent a whole morning practising, and I probably won't win a medal. Enough about us, let's talk exams, exam stress and mental health. In the studio right here in front of us is the mental health campaigner, Jonny Benjamin.

KATE - Welcome back, Jonny. Now, he's been on the Ouch podcast before, but you might also know him from 'The Stranger on the Bridge', the Channel 4 documentary all about his attempt to jump off Waterloo Bridge in London and his hunt for the stranger who persuaded him not to.

He struggled with his mental health from a young age, but during his school years there was simply no mental health education, so he was left to get on with it on his own. As a result he says he didn't get the grades he was predicted, which contributed to a downward spiral in his mental health. He was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder which is a combination of schizophrenia and bipolar, and then came his suicide attempt.

SIMON - And then the turnaround. After the documentary Jonny became a YouTuber with a channel that raises awareness of mental health issues, and last year he was awarded an MBE for his services to mental health and suicide prevention.

KATE - But what makes him particularly interesting to us today is that he runs workshops in secondary schools, which aim to provide a safe and supportive environment to talk about mental health. Jonny, do you notice a change in sort of an increase in mental health around exam time?

JONNY - Oh, absolutely. It's kind of inevitable really. There's just so much pressure, there's so much pressure. I mean there was when I was at school, but I think there's even more pressure on young people today.

SIMON - We were talking sort of generationally, because I remember getting very nervous for mine, and also I thought this is going to determine the rest of my life. But I also thought that was what you've got to go through. At what point does it spill over to something a bit more serious, and is that what you're trying to address? Or help with, should I say.

JONNY - Yes, absolutely. I mean the trouble is, our workshops, when we go into schools it's not during exam time because timetables are too full, we don't have a slot that we can go into during exam time. So actually when we should be going in we're not, we're going in kind of pre-exams. And obviously there's stress there, but the real stress when we talk to young people is around this time, right now, but there's no support for them in schools.

I mean a lot of schools we go into actually, the counselling services have been cut because of things like funding. We know that schools have got a massive problem with funding, it's been on the news, but the first thing to go quite often is the counselling or the mental health support in the schools. So many schools we've been into and they're like, yeah, yeah, we had to get rid of our counselling service, and I'm like, that's ridiculous, you know, you wouldn't get rid of a physical first aider in schools, you just wouldn't would you? Why is mental health always the first thing to sort of go?

SIMON - So the content of the workshops, can you run us through it? What is it you're covering?

JONNY - Essentially it's raising awareness of mental health and kind of explaining what it is and how depression might develop and what the symptoms might be. And not just depression but other conditions as well, but again, it's limited to what we can fit in. But it's not just about raising awareness actually, it's actually empowering them to talk if they need to talk. So we come in with a therapist that sits next door in a space and anyone can go and access that at any time before, during, after.

KATE - And what kind of mental health symptoms or conditions are these children coming and chatting about?

JONNY - Well it varies, I mean a lot of the time it's stress, it's anxiety a lot of the time, but then, what tends to happen actually is afterwards there'll be one or two that hang around. They haven't put their hands up but they just hang around and they wait for you and then they'll come up to you and they spill out all this kind of really complex stuff. Like there was one the other day actually, a young boy that came up to me and he's actually hearing voices and he hasn't told anyone. And that was, you know, it was very complex and so much going on.

KATE - And how do you help him?

JONNY - First I think, listening. I spent quite a lot of time with this young man. And first of all it's listening, listening and kind of just holding the space for them, but then it's encouraging them to… softly encouraging them to maybe find someone to talk to, whether that's family, friends.

Actually this young man, they did have a school counsellor, so he went to the school counsellor which was great. But yeah, it's kind of encouraging them to get help and also reminding them that they can get through this and if they get help now they can address it early on and maybe prevent a crisis.

SIMON - Sort of age range?

JONNY - So age range, well all of secondary school really, all of secondary school, but this year we're launching primary school workshops because we need to get it into primary schools. We're seeing younger and younger children with things like anxiety and self-harm even in schools.

SIMON- I have this mixed reaction which is, fabulous that you're there, and then I'm terrified that, oh, someone of eight, nine, is talking… It's really tough isn't it?

JONNY - Well, we're really careful. I mean language is so important, so we're not going to go in and start talking about things like depression and schizophrenia, it's more about thoughts, feelings, encouraging young people to be open about their thoughts and feelings.

I think around that age there's a stigma, this stigma that develops. I remember when I was growing up, when I was really, really small I was really sensitive, I cried a lot, I was very emotional, but when I got to around like seven, eight, people started saying to me, "Oh, big boys don't cry," you know, "now, come on, man up. Man up now." So I started to have to hide my emotions when I was vulnerable and the stigma kind of built up around that age, and I wish someone would have come in and said, "It's okay, it's okay if you cry and it's not manly."

KATE - So do you think that when we're talking about primary age children, obviously there's the debate around SATs at the moment, whether testing this age group is a good thing or not? Do you think giving kids that age an exam, is that adding to anxiety levels and stress levels and stuff, or do you think that it would be present anyway?

JONNY - No, I mean I think it definitely increases anxiety levels, absolutely. Again, there's such pressure, and pressure on teachers as well, these league tables and kind of where the school is standing. There's so much pressure. When we go into schools, I mean I had a conversation with a teacher recently actually, this is shocking, the teacher said to me that her pay level depends on the grades that the students get.

KATE - What?

JONNY - Yeah. If all the students get A she gets higher pay, but if obviously the students get like Bs, Cs, Ds, she gets… And I was like, what? She's like, yeah that's how the school does it.

SIMON - So it's performance related pay.

JONNY - Yeah, that's it, performance related pay.

KATE - Let's talk to Lucy here, because you're actually… Well, you were there dealing with that. Was that the case in your school, that your pay was linked to results?

LUCY - Yes. It's slightly more complex than that, and there are different rules depending on which schools or which authorities, or at the moment which academies you might work for. But yes, there's a broad sense in which you would be judged on your results and then your performance management would feed into your performance related pay. Yes, that does happen.

KATE - So Lucy, tell me what's your background? So you used to be a maths teacher, and what happened?

LUCY - Yeah, so I worked as a maths teacher for some time, and not just a maths teacher, lots of other subjects too, and really my experience of teaching was such that the stress and the difficulties associated with the job got far too much for me really, past the point that I think any human could bear.

And I really blamed myself and struggled for a very long time with it before coming out the other end, you know, leaving teaching and taking some time to recover and then realising actually it wasn't my fault and this was a very, very common picture amongst teachers in the UK and other countries that have a similar kind of climate at the moment, and that something needs to be done about it.

SIMON - And this is three years ago. You're now an education researcher.

LUCY - It's complex, but yes, I'm doing writing and research.

SIMON - And your bit about you can pick up the anxiety for maths teachers, what did you mean by that? And the students.

LUCY - One thing that I do at the moment is I look at recent research and try to talk to teachers about how that might help them in the classroom. And some stuff's come out recently about maths anxiety, and it's really not very well known generally as a phenomenon but what's particularly interesting about maths anxiety is it's fairly prevalent and there's a sense in which if as a teacher you have maths anxiety there's a likelihood you can pass that to students, i.e., if you have it they're more likely to have it.

KATE - What's maths anxiety?

LUCY - Yes, so that's the question. It's difficult to pin down. What we know is it's not just generalised anxiety and it's not just poor performance in maths. This is something that people experience that's a separate phenomenon to those things but also encompasses those in some way, and if you've ever had that brain freeze, that panic, when somebody asks you a mathematical question you might start to understand it.

KATE - There's a lot of nodding around the table here at the moment.

LUCY - And it's very common, you know, even as somebody who identifies with maths and loves maths I've definitely experienced it myself.

KATE - I just remember growing up every time we got into the classroom in primary school we would be given seven minute maths and I… You had like 70 questions, you had to do it in seven minutes, and that was just awful for me because I could never… I just couldn't do it on the spot, I just could not do it, and I felt terrible every day coming in thinking I'm going to have to do seven minute maths right now, you know, the first thing we do. And I was generally a high achiever at school but this set me on a down note every morning.

LUCY - Yeah, that's a really common story.

SIMON - And is there a balance though, because we all got that and that's part of it, and I hated double maths and it was miserable and so on, but…

LUCY - I'm sorry to hear that. [laughs]

SIMON - Well no, I mean it was fine, I got through it, just it wasn't fun to do. But I'm trying to work out when does it become a significant issue and when is it…?

KATE - When does it become a mental health problem?

SIMON - That's it.

KATE - And when is it just normal?

SIMON - Just what we all feel, yeah, from time to time.

KATE - Lucy?

LUCY - Yes, and you know, I'm no expert in this, I have my own experience and I have, reading other people's work, but there's a sense in which we can look at the brain and how the brain responds while people are answering maths questions. And there's a very sort of specific idea here that it's not just this is difficult or I feel bad, this is actual working memory gets completely disrupted so you cannot answer, your brain freezes up in essence, and you couldn't answer this question even if I offered you money to do so at this point because you are in this frozen response situation where your body is panicking.

KATE - Jonny, do you have any experience of these kinds of things at school?

JONNY - Yeah, well actually just my own experience, so I'll never forget when I was… I would have been eight years old. This is horrible. I was in class, in a maths class, and my teacher pointed at me and asked me to do an equation I think it was, and I froze. And she really pressured me and I burst into tears in front of the whole class and I'll never forget the shame and the embarrassment. It was awful, it was awful. Yeah, here I was, crying in front of my whole class and she just was so unsympathetic.

KATE - I guess what we're hearing from sort of Jonny's side but also from Lucy's side is that we're needing mental health support for the children, but also mental health support for the teachers, because Lucy, you're kind of on the other side of this and you weren't able to cope in that role. Is that fair to say?

LUCY - Yeah absolutely, and I think it's interesting hearing Jonny describe that because that teacher may have come across as unsympathetic and I don't know anything about that situation, but as a teacher you've got a couple of things going on there. One is that you are told to test students in a time related situation. You know, that's not something you have much choice over, and particularly there's a lot of policy decisions that get made based on that, you know, you don't have any option.

And the other thing is there's this cascade effect, if you're a teacher suffering poor mental health you haven't got the resources to support pupils, or even spot that they're having those issues. And that is a big concern for me, the more teachers we have at the moment that are really suffering mental health issues, and it's really prevalent, the less we're able to then offer students the support we want to.

SIMON - In terms of practical support I'm thinking like adjustments or allowances and I'm thinking if you're dyslexic you might get a bit of extra time. Is there anything specific around mental health that either of you recommend or that students can have?

JONNY - I've been to some schools actually where if young people are particularly anxious, because I mean the whole experience of going into an exam hall and having invigilators, and for some young people it can be really… yeah, anxiety provoking. So in some schools now they're actually taking those pupils out of that situation and putting them in more of a quieter room away from everyone else and hopefully it's kind of, yes, less anxiety-provoking.

So they are some making some kind of, yeah, allowances and giving more time for those students. Some schools, but then obviously some schools, or we've talked to some schools and they say, "We haven't got mental health issues here." So those schools, no.

SIMON - They're the scary ones… I mean I may sort of ask questions about prevalence and level but when you say there's nothing, that's when it's always worrying.

JONNY - Well, it's the same, some schools say, "Oh, we don't have bullying here." Less and less now, but there are still those schools and they're in complete denial, which is a shame.

KATE - It must be incredibly difficult, Lucy, to be a teacher and have the fate of your pay on other people. I can't even imagine what that's like.

SIMON - Kate and I wouldn't get paid would we?

KATE - Definitely not, no. Well okay, our producers wouldn't get paid on our performance, I'd say.

LUCY - Yeah, I mean for me it's one of the greater shames at the moment of the culture that we have, you know, it's very competitive, we call it hyper accountability, teachers feel like every second of their time must be spent getting students through exams essentially. If they're not spending time on that it's not efficient or effective, and actually of course all of the wonderful things that happen in schools, all of the amazing, amazing work that teachers do, you can't capture some of that by measuring it at all. And mental health, a lot of that comes under that banner of building brilliant, important role models, relationships, all of those things.

SIMON - So, it's a slightly awkward scenario here, in the scenario, if you're under a huge amount of pressure, we talked about performance related pay, what happens if you actually had someone who had some sort of learning difficulty who was in the room, so that does mean that they're going to learn differently? Do you still get measured on that, or are there allowances? What happens?

LUCY - Well, I mean this is an enormous debate, as you can imagine in the educational world, and there are some amazing experts out there who are working really, really hard to support children in exactly that situation who get ignored, who get overlooked, who might be excluded for example or actually kicked out of class because they're in a situation where their results aren't good enough to support what's happening in the school essentially.

I mean that's rare, but you will also get situations where the teacher just cannot give them the support, and this is becoming more and more prevalent. The teacher, the school, any other adults in the room, cannot give them the support they need to learn, as you say, perhaps in a different way. And everybody's in a quandary there. You know, what happens? Nobody wins in that situation do they?

And as a teacher I have to sometimes have the ethical strength to say, this isn't just about results, this is about a person, a human person who's in front of me who deserves my care and attention. And the teacher bears the brunt of that of course, that conflict, they're always in conflict when you're confronted with a child who has different ranges of complex needs.

Sometimes you're just doing the best you can with what you have and having a difficult conversation with a line manager where they say, "Well, this child isn't achieving as I would hope or their target suggests," and you have to say, but this is a human person, it's not just about the numbers on the paper.

KATE - And what would be your answer? What do you think the school should be doing?

LUCY - Well I mean, we need to talk about mental health, and what I find interesting is at the moment there's a lot of discourse and narrative around things like numeracy and literacy in schools and how important they are, what we haven't got to yet is what some people are calling mood literacy which is this idea that you can think about your own mood. You can self-analyse a bit more, you can separate yourself from situations, consider your own responses to them, and then stop and I guess mediate your own responses.

And we can talk to very small children about this, and I have my own children and this is something we talk about all the time, our own reactions, our own mood, our own minds. How can we analyse those a bit better? And that's something that hasn't quite got to schools yet on a consistent level, I don't think.

SIMON - At the risk of opening a can of worms, you're saying but you're doing that as a parent?

LUCY - I've got two children who are nine and 12 and they've had a tough time. We divorced when they were quite young and I've had to get myself through that and get them through that. And one of the ways we've done it is essentially therapy. We've sat down and talked about how we emotionally react to situations, how we can think about our effect of our words and our actions on other people. But yeah, this sort of mood literacy idea I think is really, really important.

SIMON - Thank you Lucy, thank you Jonny.

LUCY - Thank you.

JONNY - Thank you.

SIMON - We should mention that both of you have books out. Jonny, your book? What's it called?

JONNY - Yeah. It's called… Actually can I read your…? [laughs] I can't remember the full title, it's really bad. Sorry, this is really bad isn't it? It's called 'The Stranger on the…'

SIMON - Did you have a ghost writer? [laughs]

JONNY - Well, I knew the first bit, it's called, 'The Stranger on the Bridge', but the second bit yeah, so 'My journey from despair to hope'.

SIMON - Lucy, would you like me to tell you the name of your book?

LUCY - No, I think I'll be all right, thanks.

SIMON - What's your book called?

LUCY - My current book is called 'Flip the System UK: A Teachers' Manifesto' and I'm the editor of this, so this is not all my writing, but it's a collection of ideas from teachers and educationalists about moving UK policy forward essentially.

SIMON - Great stuff.

KATE - Well, please stay with us, both of you. But now it's time for a bit of a change of scene as we turn our attention to Hollywood.

SIMON - At the end of April the death of Verne Troyer was announced. He was 49. He was probably best known for playing Mini-Me in the 'Austin Powers' films.

KATE - And there's been no shortage of tributes to him, including this one from the American actor, Corey Feldman on Twitter. "He had a heart the size of his whole body. He was the finest little man, comedian ever."

SIMON - When I left my first job they called everyone together and said, "Simon is leaving us, he is a short man but he's been a giant in our office." [laughter] Eugene is sighing. I didn't know what to do.

KATE - What did you do?

SIMON - I probably just nodded awkwardly. However, elsewhere on Twitter there was this. "It should not take the death of a member of the dwarfism community to prompt a sincere and meaningful discussion about the prejudice many dwarf and disabled people face in their everyday lives, but it is a discussion we really need to have." Let's start that conversation. We have the person who wrote that in the studio, Eugene Grant. Welcome to Ouch.

EUGENE- Thank you for having me.

SIMON- Let's make this very clear at the top. You don't have an issue with Verne Troyer as an individual human being, your issue is with Mini-Me the character.

EUGENE - Absolutely, yes.

SIMON - And you went on to write, "Like dwarf performers in circuses of past days, his character only existed in contrast to others. Watching clips while writing this article, I felt sick."

EUGENE- Yeah.

KATE - So tell me, what made you feel sick then? What is the problem that you've got with Mini-Me in particular?

EUGENE- Well, that particular reference about feeling sick is talking about the way violence against dwarf bodies was turned into a spectacle in this film. And the bit I wrote about where I feel sick is watching Mike Myers' foot smashing through the body of Verne Troyer who flies into a wall and crumples against it. And there's a whole fight scene in the film in which violence against dwarf bodies is clearly glamorised and turned into a spectacle for entertainment.

And this isn't new, average height and able-bodied people have long since been entertained by violence towards dwarfs, and you can trace this back to the Romans, to court dwarves for the 16th, 17th, 18th century, things like dwarf wrestling these days.

What I was saying in the article was that actually this violence was then often recreated in real life. Academic studies show that 12% of people with dwarfism experience physical violence. If you Google the name, Martin Henderson, you will see a story about a man with dwarfism who was picked up and smashed into the ground, who was left paralysed by a stranger in a bar. And so when films like 'Austin Powers', 'Wolf of Wall Street', turn violence into dwarf bodies into a spectacle they're pretty much condoning it, they're endorsing it.

KATE - Okay. Playing devil's advocate here…

EUGENE- Sure.

KATE - Verne Troyer is nectar, he got offered a part on a big film. He, I imagine, was paid handsomely for that part. Why shouldn't it be his choice as another dwarf, to say, "Actually for me I'm comfortable with this and I feel it's fine for me to take part in it, and be paid well to do it?"

EUGENE - There are a few things about that. Firstly, is that with such a paucity of positive and realistic representations towards people in any other aspect, these representations do a huge amount of damage. Most average height people will meet very few, if any, small people in real life at all, so cultural representations like Mini-Mi, like 'Wolf of Wall Street', do huge damage, because you get people growing up for decades without any interaction with someone with dwarfism in real life, any positive or realistic representations in real life, and yet they know Disney, they know Mini-Me, they know 'Wolf of Wall Street' and that's their frame of reference.

KATE - But do you not think it is…? Sorry.

EUGENE - But hang on, just a second, to answer your question though, one of the things that really interested me about this whole personal choice argument is that this is only ever applied to people who become and sustain these stereotypes.

There's another side to this argument which is never discussed, which is the personal choice of the people whom these representations affect. Because this is what stereotypes do, stereotypes limit your ability to carve out your own life, your own image, your own independence and autonomy. And so people who are affected by these stereotypes, where are the people who champion their personal choice?

Studies show that nearly 80% of people with dwarfism have experienced verbal abuse, and nearly two thirds feel unsafe when going out. I mentioned 12% have experienced physical violence. Where's their personal choice? I don't see the champions ever coming out for their personal choice, it's only for people like Mini-Me.

KATE - Do you not think that the representation is actually getting better though in the media, in films? We've got people like Peter Dinklage and Warwick Davis and…

SIMON - Lisa Hammond in 'EastEnders'.

KATE - Lisa Hammond.

EUGENE- And Meredith Eaton as well in 'MacGyver'.

SIMON - Oh, 'MacGyver', I quite enjoy that.

KATE - Yeah. And you're saying people aren't seeing them but actually they are there, they are playing positive people instead of…

EUGENE- Well yes and no. I mean to answer your general question, yes, representation is getting better and it's been a long time coming too, but then what often happens, you're having Lisa Hammond, Meredith Eaton and Peter Dinklage doing great work, but then one of the problems that you have is that because your representation has been so bad for so long suddenly you have things like 'Game of Thrones' and Tyrion Lannister, they're talked about as if they almost compensate for that.

And let's face it, Tyrion is still a lecherous drunk and womaniser. He's such a problematic character. I love Tyrion, I'm definitely House Lannister, but I'm tired of a lot of other type of people on Twitter telling me that this now makes up for decades and decades, if not centuries, of really negative representation. It doesn't, it's a drop in the ocean.

SIMON - It's hard for me to be impartial on this one, because obviously I'm so deeply involved in it, and the personal choice bit has always been a point raised. The saddest thing about Verne, it seemed like he had a very unhappy life, and a lot of the actors that play these roles, when you scrape they say, "We don't want to do this, we want to be doing mainstream roles, we want to be doing other work where our height's incidental," but they're still funnelled into that point. So it is a choice that they actually do it, but they don't seem to get a lot of choice of other things that they could do.

EUGENE- I don't know how this influences Hollywood, but academic research shows that there's often a structure of low expectations and people being put off their ambitions, and that might well influence Hollywood as well. I can't see any reason why it wouldn't if it infiltrates other spheres of life.

SIMON - We have a clip. Verne did speak independently on his own YouTube channel and came across as a sort of fully rounded human being, as he would be…

KATE - And he had two million subscribers, so that's not a small audience that he was playing to either. Let's listen to this clip where Verne is showing people around his house. And I think he's showing them his car.

[clip]

[Verne Troyer] As you can see, I have a big pillow that I sit on, and then if you can look underneath I have extensions coming up off the pedals up to my feet so I drive just like everybody else. I actually took this out on a racetrack and raced it around the track, just to show people that I can drive, because there's a lot of questions and people wondering if I can drive. And obviously, yeah, I can. So this is my baby right now, and I'll show you the others. Let me go ahead and show you my boat.

SIMON - He clearly was paid very well wasn't he? A boat and a car.

EUGENE- A BBC salary, right?

SIMON - Well, we'll bring in some of our guests. Have you come across the Mini-Me character? How do you feel about this, or is this not on your radar?

JONNY - It's something actually I've never thought about but I completely agree. It reminds me of portrayals of schizophrenia because obviously I have a form of schizophrenia and I get frustrated with the portrayals of schizophrenia on screen. It's like come on, change the record now, there's millions of people out there living with schizophrenia, functioning, doing well.

I mean we had 'The Beautiful Mind' and that was a great film with Russell Crowe, but that's it, that's the only positive portrayal of schizophrenia that I can think of. You know, you've got everything from 'One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest' to 'Girl Interrupted'. These portrayals are so, just very negative, very negative. So I kind of really relate to what you're saying and it is frustrating, it's very frustrating because it's not accurate at all.

SIMON - Liz?

LIZ - Funnily enough on this trip to the US recently the film, 'Austin Powers' was playing when I was changing channels. And I wasn't aware that I was going to be on the show with you today, Eugene, but I actually found it quite uncomfortable to watch. The scenes with Mini-Me, I think he was shot up in the air on a chair in this particular scene and it just feels now incredibly wrong and kind of disrespectful to… the way that that body is being shown.

SIMON - There's a phrase… Lisa Hammond, who we talked about, is an actor, and she turns down a lot of these roles, and she said, "I don't want to be a warm prop."

LIZ - A warm prop, exactly.

EUGENE- I love that phrase.

KATE - Do you think 'Austin Powers' and Mini-Me would be made today? Do you think that would be acceptable?

EUGENE - I can see no reason why… I mean 'Wolf of Wall Street' was not that long ago, I can see no reason why at all. And let's not forget, 'Austin Powers' grossed over $3m worldwide and it was nominated for numerous awards. I mean if you were a money grabbing film producer, who wouldn't want to recreate that?

SIMON - Lucy, your thoughts on Mini-Me, or even wider, or maybe children?

LUCY - I hear what Eugene says and I've enjoyed some of the stuff he's written about this, and particularly for me, the point that he made about he wants to see people who are remarkably diverse and doing ordinary things like reading the news. And that really chimed with me, Eugene, I thought yes, that's where I stand on lots of other issues like LGBT issues.

We're going through a phase now where in the media, people who are different are being represented, but the difference is part of their character isn't it? It's built into the storyline, whereas if we move past that phase and they are just there doing their thing, that would be wonderful.

SIMON - You're nodding, Eugene?

EUGENE- I would love a day where the dwarf body is unremarkable, where you're neither a superhero nor are you Dopey or Doc, it's just unremarkable.

SIMON - What about an athlete?

EUGENE - A marksperson. Yes, why not?

SIMON - Forgive my quick joke in there but the closest I've ever come to that is when I go to the conventions in America for short people and there's 2,000 of us and we spend a week somewhere. Within about three or four days the rest of that city, wherever we are, are bored of us. They're absolutely bored of us, because we're everywhere and it becomes 'normal', in inverted commas. But that's one week of the year. And I have to fly to a different country.

KATE - You've recently moved up to the north. Do you find a difference in how you're perceived or welcomed in the north rather than the south within the UK?

EUGENE- This is going to be… All my northern followers are going to unfollow me in one fell swoop. Yes, 100% absolutely.

KATE - In what way?

EUGENE- And so we moved, my better half and I, and she has dwarfism as well, we moved in the summertime up north from London and the amount of abuse that I/we have received in six, seven, eight months, I think would probably already be five, six, seven years in London.

KATE - And what does that look like to you?

EUGENE- I can give you some examples. The other day I walked past a group of teenage girls who immediately started shouting how they were scared of people like me, they're scared of them, but in a way that didn't give me any reason to believe that they were genuinely sort of phobic or anything, if they were doing this for attention.

I walked past a group of men the other day who were shouting about give me a tenner to kick myself in the head. We had people shout at us when we were moving the car the other night. We were out in a bar the other night and suddenly a group of men are like, "Look at the midgets, look at the midgets," when we were just trying to enjoy a drink.

The other day I was followed very closely by a man who was filming me - he brought his daughter along which was great - filming me, and when I told him not to, he followed me quite closely, which was quite intimidating. I could go on.

SIMON - So I'm thinking about the mental health and the breadth of this, and shortly after Verne died, Tom Shakespeare, who's a short person as well, he's an academic, put something up, saying, "I've had moments where having dwarfism has just been so exhausting and I've wondered if life is worth it." And I love the fact that he said it and then amazingly people were liking it very openly. I don't know where you want to go with this, Eugene, but this must have impacted on you and how do you…? There's resilience.

KATE - Well having this abuse must impact your mental health.

EUGENE- Absolutely. I mean I have a Twitter account and I often tweet the abuse that I get on my commute and I start with "I have dwarfism. Today my commute included…" The reason why I do it, I always get an outpouring of sympathy which is lovely, but the reason why I do it is to kind of try and shine a light on how prejudice affects your daily life. And I often say that prejudice doesn't need to be big or extreme, and we've talked about violence in the show, but it doesn't need to be big or extreme, it just needs to be little and constant enough to just chip away slowly at you day after day after day.

And then what frustrated me, to bring this back to Verne Troyer, after he died, what you saw, and you saw this with Stephen Hawking as well, suddenly this person's disability or their difference, for which they encountered so many barriers, is suddenly removed. And then 'a big man in heaven' or 'they're free from their wheelchair', but that's only done after they've died.

KATE - But what is your toolkit for managing the abuse that you get to keep your mental health in check?

EUGENE- Well at the moment, I was talking to my better half about this the other day, and she was talking about how much she walks around with headphones on listening to music and that kind of shuts you out from a lot of the outside world. I did this the other day and my commute was a lot nicer, but there's part of me that kind of does that and also doesn't want to very much.

JONNY - Can I ask a question? Do you react to it? Like when you get that abuse, do you respond to it or do you just kind of block it out, or how do you respond to it?

EUGENE- A good question. It varies completely. Sometimes I've got the perfect wittiest response, sometimes I can educate, sometimes I just want to go hurting people.

JONNY - Yes of course you do, of course.

EUGENE- Sometimes I feel like crying. Sometimes I just ignore it. Sometimes I crumble. One of the things that irritates me is that I often feel like there's a pressure on dwarf and disabled people to have the perfect response and to be like witty and educational and… Because also, don't forget though, that often these instances are public and so you've got witnesses.

And so not only do you have to try to come back to the person who's done this, you have to educate everyone who's watching and that's a huge pressure. And it's not on dwarf and disabled people to be your kind of educational experience, it's too much pressure.

JONNY - Do other people get involved as well ever? Do other people fight your corner?

EUGENE- Very rarely. Very, very rarely. A few times it's happened and I've really appreciated that, but it's very rarely. Sometimes what happens is if you get a group of people and one of them is an absolute nightmare, incredibly abusive to you and you get the sort of nice friend person who is in that group who then apologises or gets them to shut up or something like that. But they definitely stay friends afterwards, whereas if one of my friends did that it would end right there.

JONNY - Of course.

SIMON - There are quite a few… I'm thinking of Sinéad Burke, there's two or three other women and there's a group of you who are doing some great stuff.

EUGENE- Sinéad's excellent.

SIMON - Do you think there'll be change? What will this change look like?

EUGENE- Will there be change? I think so, but I think change is slower and more complicated than people think. And you've got activists like Melissa Thompson and Rebecca Cokley, Cara Reedy, and you've got John Young, who is a teacher who runs marathons, who is the first short person to ever complete the Ironman triathlon, he did a huge piece in the media recently for the Boston Marathon. So you are getting that, but it's slow and it's complicated. A single show like 'Game of Thrones' doesn't change the world. It should be the first of many.

SIMON - Thank you, Eugene. Please can you join the others on our sofa? We don't have a sofa, I don't know why I've said that. [laughter] Please stay with us while we speak to Niamh who's one of the Ouch team who's got a roundup of other disability news. So Niamh, if I say #hotpersoninawheelchair…?

NIAMH - Niamh says Kate Monaghan. Obviously.

KATE - Yes.

NIAMH - Guys, seriously. Okay, so this is a hashtag that came about a couple of weeks ago but it's got a bit of a back story to it, it's a bit weird. So four years ago a former American game show contestant called Ken Jennings, he was a contestant on 'Jeopardy'. Anyone? Yeah? Okay, so he posted the following tweet. "Nothing sadder than a hot person in a wheelchair."

This original tweet then resurfaced last Sunday when American YouTuber, Annie Segarra, also known as Annie Elainey, she adapted it so that it read, "Hot person in a wheelchair," and then she completed her retort with this little caption that said, "Cry about it babe." And it was so good. She had a picture of herself and she was wearing this little pleated skirt. She basically looked like she'd walked out of the movie, 'Heathers', it was great. And she had a really good pose on her and her response received, I think nearly 400 retweets and around 3,000 likes, and throughout the week got a fantastic response from around the world.

Because what was great was the hashtag really caught on, it went viral, and this hashtag got a tidal wave of stunning photographs, some of them were really, really gorgeous, but then you have everything from people who were quite heavily made up and they've got really cool dresses on, they've got their hair done, everything from that down to people just wearing trackie bottoms and a t-shirt.

SIMON - So, lukewarm in a wheelchair. [laughter]

NIAMH - It depends on how you want to see it I suppose. But I suppose it just really continued a conversation about our attitudes towards disability and beauty I suppose, about how they can kind of be seen as mutually exclusive I guess.

SIMON - Did you put a picture up of yourself?

KATE - I did not put a picture up, but I said, "There's nothing sadder for you because you are not hot enough to get with this."

EUGENE- Nice.

SIMON - Did you really?

KATE - I did. Yes, my friend. [laughter]

SIMON - Now, not connected, are men allowed to do it or is it just exclusive?

NIAMH - Oh yeah, there were plenty of blokes doing it as well. Yeah, plenty, plenty.

KATE - Always jumping on our things, trying to jump on our hashtag. What's next?

NIAMH - Next? Well, I just want to turn your attention to my jacket because…

KATE - Which is a delightful jacket today.

NIAMH - Thank you. I call it my Andrew McCarthy jacket because I feel like I'm in 'Pretty in Pink'.

KATE - Could you stand up so we can have a proper look at this?

NIAMH - Yeah.

KATE - So it's a grey jacket she's sporting with blue…

SIMON - Check.

KATE - Check.

NIAMH - Yes, but I'm referring to my lapel.

KATE - Oh, sorry, sorry.

NIAMH - Yeah, I'm referring to my lapel. I have actually been sitting here the entire time with this on. Have you noticed?

KATE - Yes.

SIMON - Yes.

NIAMH - You have noticed? Okay.

JONNY - Yes.

NIAMH - Okay, good, because it's a seamless segue into the next story. Last week was a priority seating week, or a priority seat week, to mark a year since the launch of the Please Offer Me a Seat badges.

SIMON - We had the launch on the show didn't we?

KATE - We did. I was one of the first people to get one and I went and trialled it on the tube to see whether or not it worked.

NIAMH - And?

KATE - And it did work. I got a seat and I've kept my badge ever since and pop it on, and those days when I just don't want to actually ask somebody I just sort of do a little motion towards the badge and it works quite well.

SIMON - So a year later? What's the sort of research, what do they say?

NIAMH - So the general consensus is that it's working fairly well, but it's not always. I've personally had a couple of experiences where I've seen someone wearing a badge and I have intervened. But I suppose that's because people are looking at books and…

KATE - What do you mean by you've intervened?

NIAMH - I've said to the person, "Do you want me to help you find a seat?" And I feel a little bit awkward about doing so, but I sort of prod someone and say, "Hey, do you mind offering this person your seat?"

KATE - And so you have a disability yourself?

NIAMH - I do, I have congenital hemiplegia.

KATE - Okay, so do you need to be wearing the badge? Do you need a seat?

NIAMH - I don't wear it, I prefer to stand to be honest. I like being able to sort of challenge myself to say right, I will be able to hold my balance. And it does help me improve my balance.

SIMON - I understand that, as an athlete. [laughter]

KATE - Why do people keep laughing? So you haven't been in the awkward situation where you've had a seat, you've seen someone with a badge, and then you're saying to somebody else, "Oh, get up."

NIAMH - Oh no, I have given it up before.

KATE - No, but you're not asking somebody else to give it up, because I have been in that situation where…

SIMON - "I've got the badge, do you want to share my seat?" [laughter]

KATE - Simon, stop it. But I've been in the situation where I've been sat down, seen someone with a badge and said to the person next to me, "Would you mind getting up to give this person a seat?" and then I've realised, they're like why don't you give your seat up, you lazy woman? And because I haven't had my badge on because I had a seat. So yeah, that's always an awkward one.

SIMON - Also, I thought the whole point of the badge is that you don't have to have four people getting involved. Someone sees the badge and they give up the seat. I have heard some people, they give up the seat and then the person says, "Oh, what have you got then?" And then you start this whole conversation about… Is the general consensus it's a good thing, it's just a bit more prolonged there?

NIAMH - Yeah, general consensus is that it's good. There's a little bit of a way to go, not everyone was totally satisfied with it.

SIMON - 30,000 people have got them?

NIAMH - 30,000 people, yeah, the vast majority of them I think are responding well to it, but that doesn't mean that they walk onto a carriage and immediately five seats are offered to them.

KATE - No. And I think it's difficult, because when I did live in London often my commute would be at eight, nine o'clock in the morning on the Victoria Line which is rammed and the likelihood of getting a seat at those times, you know, it's never going to work then. But I like it.

SIMON - I think there's a very valid point, it's a start, and well done, this is great, and it's for a specific group as well I think.

KATE - Yeah, it's for people who have hidden…

SIMON - Non-visible, yeah.

KATE - Yeah, non-visible disabilities, that it really benefits. So for me when I go on the tube, when I'm walking around it makes my life a lot easier. But what would make my life really easy is if I could have an accessible tube where I could use my wheelchair and get on and then I wouldn't have any of these problems at all.

SIMON - Well, you'd also bring your own seat.

KATE - Exactly. Now, Liz Atkin is with us who is an artist who gives her pictures away for free to fellow tube passengers, and that's your answer to your own hidden disability isn't it, Liz?

LIZ - It is, yes.

KATE - This is so seamless. Whoever put this programme together, I mean they just deserve some kind of award because it's just so impressive.

LIZ - So yeah, my experience on the tube is often very challenging, so I've kind of found a way to solve it, which is a bit peculiar maybe.

KATE - Okay, so why do you have problems on the tube?

LIZ - I have a compulsive illness called dermatillomania, or compulsive skin picking and I suffer from anxiety quite badly, so I was struggling a lot commuting, because I would either have a panic attack and need to get off the train in a packed situation, but more prevalently I'd be picking very badly on the train, because the condition is quite a challenging thing when I'm sedentary.

So I'd pick my fingers very badly and they'd be kind of bleeding by the time I get to work. And it was driving me crazy really. I've had the condition since I was very young, so it's quite a complex disorder and this kind of weird solution came out of running out of a sketchbook on my journey and picking up a free paper which was on the seat next to me.

KATE - So did you take a sketchbook on the journey in the first place?

LIZ - I did. It became a way to sort of just relax and refocus and it kind of was an accident. So I didn't train as an artist, actually my background's in dance, so I've come to this quite late in my life. So about five years ago I was quite unwell with mental health problems and I had a lot of time off work, and yes, my skin picking had come back very, very badly, so I was in a lot of distress. And then I got a job in north London so I was commuting, kind of a two hour commute, and as we've talked about, the tube is a very challenging thing for a lot of us, but if you have a sort of challenging issue that can present itself in a packed tube it's quite a hard thing to cope with.

And it was causing me a lot of distress and I started carrying a little sketchbook to just kind of draw in while I was commuting. And I was finding that drawing was a good solution to the anxiety, it would just kind of settle me and calm me down. And of course drawing, my hands are very occupied, so the skin picking was kind of quietened.

And then one day my sketchbook ran out and I had another hour and a half ahead of me and it was a packed tube in rush hour and I felt the panic attack rising, I looked at my fingers and I was picking my fingers and I thought, I need to draw, I need to do this now. And I grabbed the newspaper that was next to me and I thought well, I'll just doodle on it, you know like you do when you're on the phone or anything. I didn't think of it as some grand idea. And I doodled on it and I left it on the seat and I took a photo of it and now that is something I do every day.

SIMON - And you give?

LIZ - And now I give the drawings away to passengers.

SIMON - Do they know you're drawing them or are you drawing something completely…?

LIZ - I'm drawing over the images that are in the paper, so anything, the picture of a celebrity, an advert, the way that a bit of copy is placed on the page becomes something I'll graffiti. And I draw with charcoal so it's very messy. Part of that is that once I'm messy I can't pick my body, I can't kind of touch my face or pick my fingers. And charcoal has a very grainy texture to it so that really sort of connects with the feeling of the disorder, it's quite a tactile disorder.

SIMON - And art therapy's an idea but you kind of created your own.

LIZ - It's kind of art therapy. I kind of created my own. And I've given away a huge number of these things. So on a busy day I do about 60.

KATE - 60?

LIZ - So I've given away more than 16,000 drawings.

SIMON - How do people react?

LIZ - Well, basically this didn't start as something deliberate, so I started realising they were accumulating on my lap because I'd pick up a couple of newspapers and then I'd have a few of them that I'd been drawing on. So to start with I wasn't bold enough to have eye contact with anybody, and I knew people were looking, I could feel it, but I started sort of leaving them on the seat and just scribbling, 'free art, please take it', this is like four years ago, and then slowly it's evolved into knowing that there's a person directly opposite me who's looking and wondering what's going on. So I started just leaning forward and saying, "Would you like this?"

And to start with people don't know what to do. There's often a kind of, "No, thank you," you know, people shut down and a lot of what we've just talked about with the kind of tube issues, people aren't kind of very aware, they're on their technology, they're looking at their phones, they're reading a book, they've got their music on. And it's quite an odd thing I'm doing I guess that people then sort of look across and wonder.

KATE - Do you explain why you're drawing?

LIZ - Yes. I started carrying a postcard about two years ago, because also, you know, I realise that I'm drawing because I have this condition that a lot of people don't know what it is, so I thought well to… And a bit like Eugene was saying earlier, that a conversation might start in a public place and people are then engaged. So I then thought, well there's ten or 12 people, or probably more in rush hour, that are crushed around me wondering why I'm drawing, I could be telling them, "I'm drawing because I've got a mental health condition and this is what's helping me."

But also, getting people to join in, because then I realised that that can be a message that reaches lots of other people. So more recently, or in the last couple of years, there are often people that are in the carriage that have the condition and don't even know it has a name. So it's in the family of kind of OCD conditions, so people with the hair pulling disorder, which is called trichotillomania, it often gets a lot more press. People have heard of that, you know, if you pull your hair out because you're stressed or you're anxious people have often heard of that.

People often don't know that skin picking, aside from it being like a general thing that all humans do, can be a really complex and challenging mental health problem. So I realise that if I give a postcard out with this drawing, somebody in the carriage might have it. And I now know the statistic of one in 25 might suffer from these conditions. And I get emails every day and messages every day.

KATE - Well if you're giving 60 away and it's one in 25, it's got to be a high hit rate.

LIZ - It's a high hit rate.

KATE - Have you ever had any sort of bad reactions to it?

LIZ - Yes, oh yes. I've had charcoal snatched out of my hand and thrown to the ground, people accuse me of littering, people call it dirty. Yes, of course. Humans are challenging as well as being kind. So there have been situations that have been really bad and Eugene was talking about this as well, in that often people don't intervene or support, so that becomes a moment of this is a political thing where I could actually say, "This is my stuff and I'm doing it here and I'm not trying to sell something or impose this on anybody's lives, it's just something I'm doing right here."

SIMON - So if someone picks up a mobile phone and it starts getting towards me I immediately think they're going to take a photo of me, and I'm really on edge. So I can imagine some people might go, oh what's she doing about me? So you have to kind of almost break that. Do you ever tell them while you're doing it, this is why…?

LIZ - Yes, absolutely.

SIMON - Yeah, okay.

LIZ - And wonderful conversations happen. The person sitting next to me that I know, you know, you can feel if someone's reading over your shoulder when you're on your phone or whatever.

KATE - I love doing that to people.

LIZ - I feel that, it's very… People are nosy, right? And if I feel that I know that's a person who's wondering, what is this woman doing? So very quietly I smile and I just pass them the postcard. A lot of people, they gesture, no thanks, kind of thing, so then the person opposite will be looking so I'll give them a postcard and then I've got a load in my hand so then it becomes clear, oh, you're giving out postcards.

So then people are more willing to take a postcard. And that's enough for five or six people around me to then have read it and then be looking back and wondering, oh right, you're drawing because of this thing called skin picking. And then someone normally speaks to me and that means that all these people are going, "Oh right, so how often do you do this?" you know, that's the first question. "Do you do this all the time?" And then I can say, "Well actually, this is my kind of recovery tool, this is what I do when I'm travelling, it really helps me." And then that little group of people might go away and say, "I saw this woman drawing because she's got a mental health problem," and that's a bit of advocacy that is free.

SIMON - We mentioned this at the top of the show, you're here to tell us about the international conference you've been to in the United States about hair pulling and skin picking. When you met other people with… you know, in this family, at the conference, did lots of people have their own mechanisms? Does anyone have the same as you?

LIZ - Well, I was sort of sharing that as a tool because the condition at the moment, there's no cure for it, you can't get a pill that's going to stop it necessarily. Some people respond to medication very well, other people don't, so at the moment, the reason the conference is so significant at this point is they're doing a big study in the States about why humans have these conditions.

So it's everywhere in the animal kingdom as well as humans, you know, parrots that pull out their feathers, cats and dogs that bite at their bodies, mice that pull their fur out, fish that pick off their scales with their mouths, this is everywhere in the animal kingdom. So grooming can become a kind of overactive thing and they're not quite sure how to intervene to stop it. So lots of things exist on the market to kind of help people with these conditions.

So tactile toys like squeezy toys, or those kind of clicker fidget toys, those sorts of things are really useful because they occupy your hands. The conditions are very repetitive, so it's all about the movement of my fingers and my hands. So drawing is a good solution for that because I can reoccupy it in a different way.

NIAMH - Speaking of mess, it did occur to me as you were speaking, Liz, as you started talking about the charcoal and the mess, I thought if you have it in your pocket all the time how often do you accidently wash it?

LIZ - Very often. [laughs] Actually the worse thing is that I have to put all my dark wash in together as most of us do, but often there are a few bits of charcoal just rattling around the bottom of the washing machine at the end of the wash.

KATE - I'm looking at you and I can't see any sign that you have a condition of this kind.

LIZ - Exactly.

KATE - Is it that you hide it well or is it that you are now quite recovered and it's under control?

LIZ - It's a bit of both and this is something to talk about. Basically the condition is complex, as a mental health condition I would hide the condition from everyone, so actually my arms and my back and my chest and my feet, my knees, would be very, very badly picked. I'd have open wounds under my clothes all the time.

I'd pick my face very badly so I would be able to cover that up with makeup, but often these conditions are hidden, they'd be under my clothes so how why would you know? The only kind of outward sign of it now is probably that I still struggle with my fingers and I do pick my fingers, but the body picking has really reduced massively by finding this way to look after myself. It's important.

KATE - Thank you, Liz.

SIMON - Thank you, Liz. If you haven't already, we've made a video, it's a brilliant video of you, doing your sketching on the tube. Check it out, it's on the Ouch Facebook page.

KATE - Now, there's no music to end on this week, but we do have one last thing to tell you about before we go. Is anyone around the table a 'Britain's Got Talent' fan?

NIAMH - I've watched it. Oh look, it's gone very quiet in here.

KATE - It's lovely Saturday night entertainment.

SIMON - I'm with you. These things are great, these are good ones. We're going to change their minds.

KATE - Yeah. It goes against the grain to plug a programme that's not on a BBC channel obviously, but there are now two disabled acts taking part, so if you're not watching you really should be.

SIMON - One of the acts is comedian, Lee Ridley, also known as Lost Voice Guy, who you may have heard, he was on last month's podcast.

KATE - As well as a few before that as well.

SIMON - That is, we are ahead of the curve.

KATE - And the other one is a dance group called Rise. One of the group's members is a 13 year old who was injured in the Ariana Grande gig bombing in Manchester and she's a wheelchair user as a result.

SIMON - And the rest of the group, there's this lovely story, she wants to go back to dance with them, they're saying, "What are we going to do?" What the rest of the group do is get into wheelchairs and started doing the whole dance routine so it becomes part of it.

KATE - Well, they use wheelchairs as props don't they, but not in a cringy way and actually like a really cool way and she gets up and dances and then she sits back down. At the audition stage the judges and the studio audience raved about it.

[clip]

[Simon Cowell] And the fact that you can come onstage, do what you did, and make such a positive statement and with your friends, I'm very proud of you. In fact, I salute you. [applause] But we've still got to vote.

[Amanda Holden] David?

[David Walliams] I'm going to say yes!

[Alesha Dixon] It's a yes from me, girls!

[Amanda Holden] It's a yes from me.

KATE - But the golden buzzer wasn't sounded, so we don't know…

SIMON - [makes buzzing noise]

KATE - So we don't know for sure if they're in the live semi-finals, but it's really worth watching, it really is.

SIMON - Well, hopefully we'll have a little bit more news on next month's podcast, so come back and listen to us more.

KATE - And that's it for this month. Thanks to our guests, Jonny Benjamin, Lucy Rycroft-Smith, Eugene Grant and Liz Atkin. Your production team today have been Niamh Hughes and Beth Rose and the studio manager is Robbie Heyward, the producer was Daniel Gordon.

SIMON - Please contact us. You can tweet @bbcouch, email ouch@bbc.co.uk or find us on Facebook. And don't forget, there is a podcast on this feed every week, including the return of the autistic takeover with Robyn, Jamie and Lion. We love them.

KATE - We do.

SIMON - That's coming soon. Like us, share us, and for goodness sake, leave us a review on whatever podcast service you use.

KATE - Goodbye.

SIMON - Bye.

- Published4 May 2018