The disabled teenagers whose identity crisis led them to modelling careers

- Published

Caitlin Leigh and Brinston Tchana have modelled for high street retailers including Primark and River Island but their interests in fashion were only piqued after they became disabled and felt they had lost their identities.

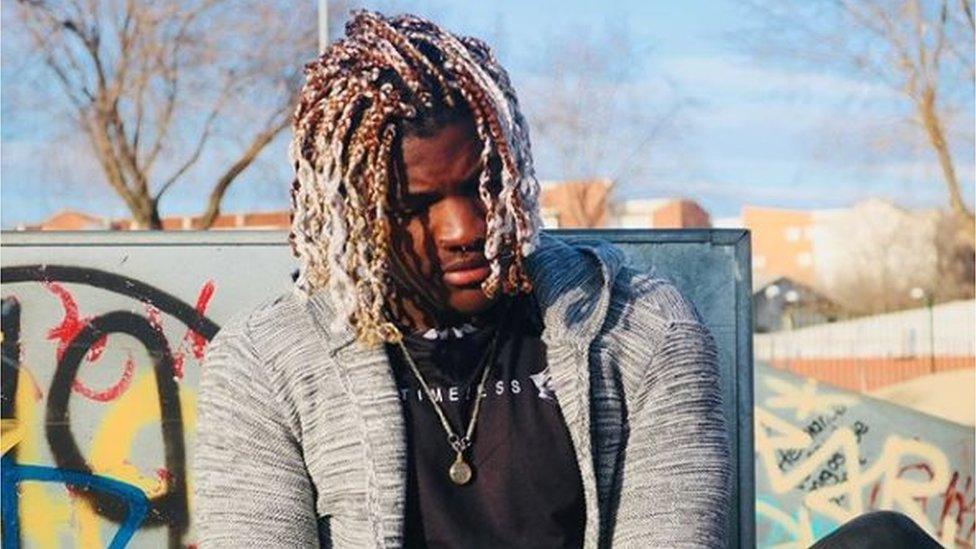

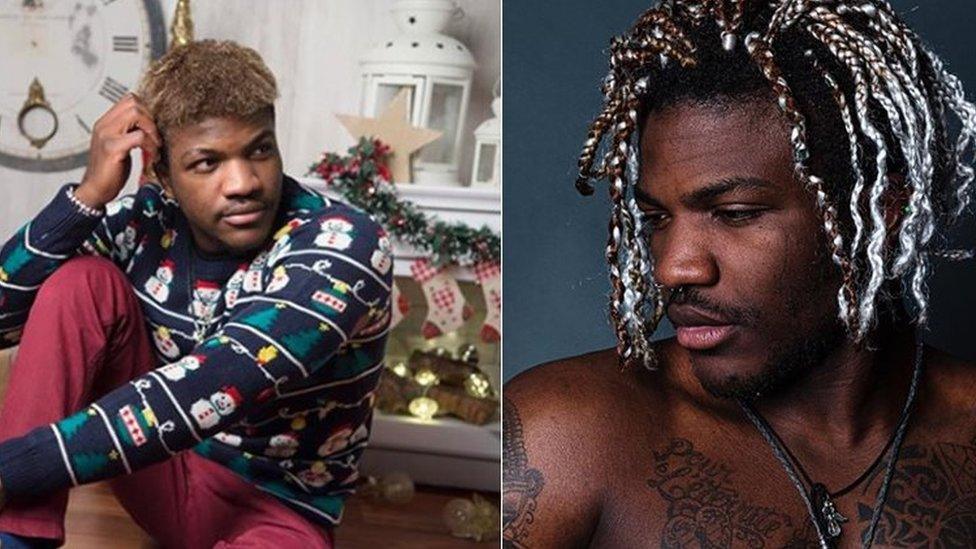

With more than 15,000 followers on Instagram regularly checking-in on his style, Brinston has hopes of one day modelling at New York Fashion Week. But a few years ago, fashion couldn't have been further from his mind.

At 17, he was months away from signing up to play for a professional football club in Spain, where he'd grown up, and life was good.

Before the big signing he went to a nightclub with his friends. They spent the night dancing, carefree and excited about their futures and later walked home together through the dark streets laughing and chatting.

But, out of nowhere, a car came from behind and struck them.

The emergency services were called but three of the friends died that night and Brinston was left in a coma. When the young footballer came around he was told he had been paralysed from the waist down. The driver had been drunk.

It changed his life completely, with his professional sporting ambition off the table and a different body and appearance to get used to.

Until then the idea that fashion could be interesting or fun had passed Brinston by. "My mum bought all my clothes. I had been more focussed on football and didn't care about anything else," he says.

Now a wheelchair-user, he felt he had to start caring about his image because of the shift in how people perceived him.

One day, while waiting for a friend in his new home in Birmingham, England, and shivering from the cold in a thin jacket, a man approached Brinston.

"This dude just came close to me and gave me £5. I was like: 'Why are you giving me £5?' And he was like: 'You're not homeless?'."

Brinston was taken aback. He felt that, had he not been in a wheelchair, this wouldn't have happened.

He says he has learnt some people think he's homeless while others presume his tattoos and injury are gang-related or linked to violence. They're not. He feels there is sometimes a racial element to this way of thinking - "being black in a 'white country' with a disability is not easy," he says.

But over time, Brinston discovered that if he dressed stylishly, fewer unwanted assumptions would be made about him.

It also shifted how he viewed fashion and he started to adopt it as both a way to express himself and as a shield against the outside world.

He bought high-end jackets and shoes which looked smart and elegant, but also looked good and were comfortable for him as a wheelchair-user.

"When I'm at home and feeling safe, I'll put on casual stuff and I know nobody is going to judge me. But when I'm out, I feel like I need to show that I am not that vulnerable."

Like Brinston, using fashion as armour is something Caitlin Leigh identifies with and has employed since becoming disabled - she began to lose her hair and have seizures a year ago.

Her symptoms initially baffled doctors. She was diagnosed with alopecia and, after many tests it was determined that she blacked out as a result of her mind trying to block difficult situations - a condition referred to as dissociative seizures thought to be brought on from earlier episodes of depression, anxiety and stress.

The seizures happen every couple of hours and Caitlin started to use a wheelchair to ensure she was safe.

"The minute I started losing my hair I decided to go for a buzz cut," she says. "I just felt like nothing in my wardrobe suited me, but over time I slowly started finding my way in fashion."

Previously, Caitlin's hair had been long and she loved colouring it. Now she describes her overall style as edgy and indie.

"Fashion is a way for me to express myself. Before it was my hair, now it's my fashion. And it just fills me with confidence. If I feel a bit different, I feel untouchable."

Often choosing statement pieces with bold colours and patterns she says her style helps challenge stereotypes that people have of wheelchair-users and acts as a "gateway" to conversations.

Listen to the podcast

Disability and fashion: Giving people something to stare at

Caitlin loved experimenting with her hair before developing alopecia and Brinston was about to sign as a professional footballer when he was paralysed in a car crash.

Listen to the two models talk fashion, disability and redefining who they were.

"I find people feel they can approach me more if I'm wearing something unusual or if my hair is different, because they see that as the talking point.

"If I go out and I look confident and I'm dressed confidently, people definitely have a more confident mannerism towards me. If I'm just wearing normal comfy clothes, people see me as just a person in a wheelchair."

But it gets complex. If you do express yourself positively it can be double-edged. Some wheelchair-users feel that when they "dress well", or in a way that challenges stereotypes, it can make people think they're not disabled.

Brinston says he has experienced this. On one night out with friends, he wore his most expensive shoes - £700 Balenciaga's . A man came over to him and asked if he was faking his disability.

"Why would I be faking it? How I wish I could be like you, just dancing around," he told the man. "I think the negative part is that if you dress well then people think you're faking it just to get money."

But that's not to say disabled people should feel they need to dress-up.

"It does take time to have the confidence to think about fashion for yourself," Caitlin says. "I think that's the biggest thing for young people growing up, that they feel like they have to dress for other people, and that's not how fashion should be."

Even though fashion is an integral part of Caitlin and Brinston's lives they say shops need to become more accessible and clothes - which remain presentable even after you've been sitting in a wheelchair all day - need to become more mainstream.

The disability charity Purple estimates the British high street loses about £267m a month because of this inaccessibility.

Both Caitlin and Brinston say fashion helped them accept their disabilities and neither think they would be working in the industry if they hadn't become disabled.

"Finding my style has given me the confidence I've needed to pursue the fashion career I'm now living," Caitlin says. "It doesn't matter what your disability is, you can still look bomb."

After watching shows at last year's London Fashion Week, she's determined to be on that catwalk one day.

"People just need to have the confidence to take that step - to book a disabled model - because we are human beings and it is really important we are represented."

Brinston agrees and says after spending years struggling to accept his disability, fashion also helped redefine his identity beyond football.

"It's given me confidence to say 'this is who I am'."

For more Disability News, follow on Twitter, external and Facebook, external, and subscribe to the podcast.

Related topics

- Published22 November 2019

- Published26 August 2019