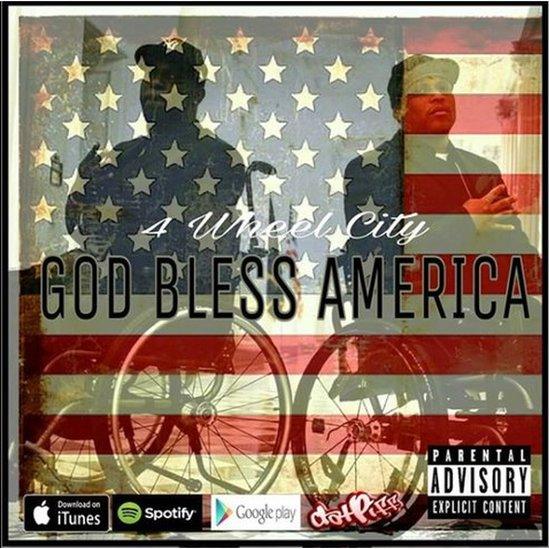

Rap duo 4 Wheel City and the Krip-Hop career they never expected

- Published

4 Wheel City formed as a rap duo after both Namel and Rick were shot and paralysed as teenagers

Black New Yorkers Ricardo Velasquez and Namel Norris were shot and paralysed when they were teenagers. As rap duo 4 Wheel City they have received global acclaim and raised the prominence of Krip-Hop - a sub-genre of Hip-Hop which puts disabled matters front and centre and lets them express the "double drama" of being in two minority groups

Rick headed home from high school. It was the summer of 1996. The holidays were approaching and his sweetheart was pregnant. But in a single moment everything changed.

A gun was fired nearby and he was hit by a stray bullet.

"I don't know who shot me, but I ended up in a wheelchair," he says.

In the same Bronx neighbourhood was 17-year-old Namel. He was at home with his cousin.

"We grew up in the street so we were involved with guns and one day he was playing around with one," Namel says. "It went off and the bullet struck me in my neck."

Both teenagers, wounded at different times, were paralysed and became wheelchair-users.

They now had to come to terms with being part of TWO minority groups - black and disabled.

"It's like you're doing a double life sentence," Namel says.

"Imagine that, being black and disabled," Rick echoes. "That's a double drama. It's like your voice is not heard in a double way. You've got all these barriers."

In 2020s language, having two 'protected characteristics' like this is referred to as intersectionality and could lead to double celebration - or double the discrimination.

It was Namel's mum who first met Rick. He gave her his number and said Namel could call him.

But after Namel was discharged he simply wanted to get back to what he'd always done. He met up with his old friends, but it wasn't the same and all the dynamics had changed now he couldn't walk.

"One of my friends I used to rap with, wasn't hanging out with me as much," he says.

Namel contacted Rick who said he had experienced the same kind of thing with friends and family who no longer knew how to talk to him because he was in a wheelchair.

He began to hang out at Rick's recording studio because it was a place he felt he would "be understood, be heard".

The pair wrote Hip Hop tracks together as Rickfire and Tapwaterz but the rap market was so saturated that it was difficult to stand out.

At the same time, Namel was getting fed-up with the constant questions people kept asking him about his injury - "questions like, 'Are you going to walk again?' and, 'Does this work?'. I was tired of people asking."

He took his frustrations out on the page and wrote In My Shoes - a track which dealt with those personal questions.

"It felt good to be able to express myself like that," he says.

Getting more political, the duo penned another song - The Movement - about the inaccessibility of shops in New York.

Listen to Namel and Rick rap and chat on the BBC Ouch podcast...

The paralysed duo tackling gun violence and discrimination through Hip Hop

It made an impact. When they returned to the street where they had filmed their music video, the stores had ramps.

"That's the song that really put us on the map," Namel says. "Music has always been a form of protest."

Their music falls within the little-known sub-genre Krip-Hop - a movement which gives disabled hip-hop artists a platform to educate and deal with ableism alongside racism and sexism.

Krip-Hop was founded by Leroy F. Moore Jr. an African American writer and activist with cerebral palsy who wanted to use rap culture as a way to reclaim negative language associated with disability.

The latest album from 4 Wheel City, Quarantine Music Volume 1 - released during lockdown - dives into the double minority identity of being both black and disabled

The track Crazy World and its accompanying video reflects upon the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests which followed.

Namel says: "The song is about how crazy the world is right now and being able to deal with it as a person with a disability."

The video flits between Namel in an ambulance wearing a facemask on his way to hospital, George Floyd's death and the protests.

The pair say the death of Mr Floyd and the subsequent BLM protests has helped them explain to others how they felt when their lives altered through disability.

"When your life gets changed or flipped upside down it makes you think differently," Namel says. "I think that's why a lot of people out there are protesting right now because I feel like they had a wake-up call."

Namel and Rick channelled their wake-up calls through lyrics which often have a political edge as they put into words what being black, disabled and American means to them.

4 Wheel City say there is a lot to be done to reach equality and while they want change on a global scale they also want to affect change in their local community.

Mount Sinai Hospital commissioned them to rap about pressure sores - a serious problem for people with spinal cord injuries who may sit in their wheelchair for long periods of time - and a local organisation, Being First, recruited them to talk about the perils of gun violence to school students.

But there are obstacles within that.

"I don't want to be racist," Rick says, but the fact is "white people run most of the organisations" and yet, "if you come to the black community most of us are in wheelchairs due to injuries like gunshots".

Namel adds: "Our talent could be used to make a difference".

4 Wheel City have previously rapped at the UN and want this month's 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which prohibits discrimination based on disability, to be marked with meaningful movement forward.

Namel says: "I know it can be discouraging and it's easy to say, 'well I'm black and they don't want to listen', but what Rick and I did, we tried to remove that barrier [through music]."

Rick adds: "Don't be afraid to be different and go out there and put your voice out there and embrace the struggle."

The rap duo last performed in the UK in 2012 at the London Paralympics, a unifying and positive event for disabled people around the world. But they say the summer of 2020 with Covid-19 and BLM protests has, in some ways, made them feel the same.

"It was being black and American and disabled," Namel says. "I felt that sense of pride. Just knowing that our music matters on the world stage."

For more Disability News, follow BBC Ouch on Twitter, external and Facebook, external, and subscribe to the weekly podcast on BBC Sounds.

- Published19 June 2020