The Archers tackles the 'hidden' connection between disability and modern slavery

- Published

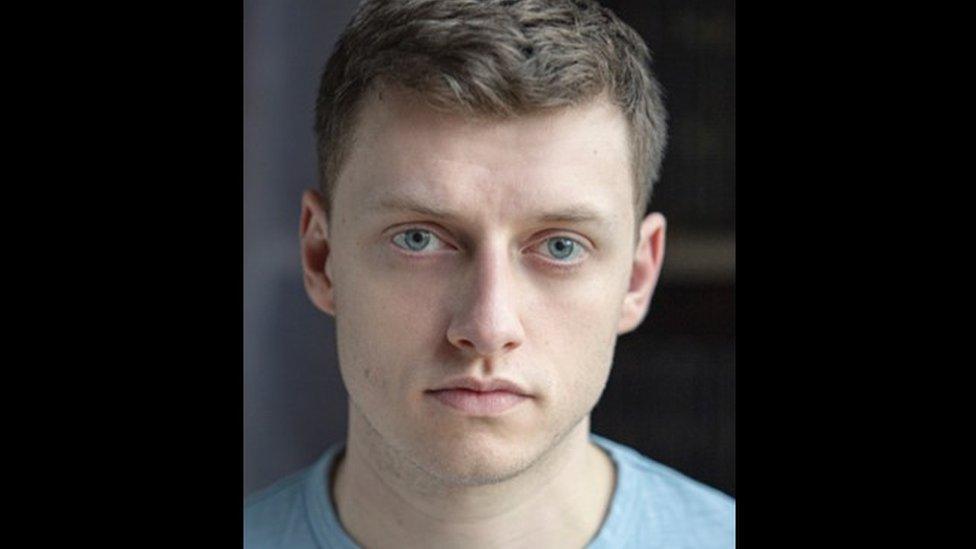

Luke MacGregor plays Blake - one of the three men enslaved by a builder in Ambridge

In the latest episode of The Archers it was revealed that three men, kept as slaves on the outskirts of Ambridge, have a learning or mental health disability. It is a side to modern slavery that experts have described as "hidden", as Mike Lambert explores.

Like other listeners to Radio 4's The Archers, I've been gripped by the latest twists in its modern slavery storyline.

Since March, we've known about three British-born men - Blake, Jordan and Kenzie - who have been enslaved by builders and kept at a secret location near Ambridge.

Last night, we heard the men talk amongst themselves for the first time and it was revealed they all have a learning or mental health disability.

According to the Global Slavery Index it is thought there are up to 136,000 victims of modern slavery in the UK.

This is the appalling reality that The Archers' editor, Jeremy Howe, has chosen to confront and he also wants to challenge some of the stereotypes about this trade in human misery.

"It's not simply a problem involving immigrant labour," explains Howe. "It can be a British problem involving British slaves and British gang-masters."

In so doing, he has posed the question of what mind-forg'd manacles keep three, British-born, young men enslaved to a pair of unscrupulous builders.

My interest in the connection between disability and modern slavery began in 2017, after a chance meeting with a former victim.

The victims of the Rooney gang lived in squalor, police said

At that time, there had been a crop of news stories about the Rooney gang - a Lincolnshire-based family convicted of trafficking 18 men into hard labour for their driveway resurfacing company.

I had read how these victims were regularly beaten, subjected to mental cruelty and "institutionalised" into slavery - one of them for 26 years.

Then, one Sunday, on a train from Doncaster to London, I met a 23-year-old man called Chris (not his real name).

At first, as Chris described his difficult life and recent trip to visit his abusive, alcoholic mother, I was struck by his chatty and trusting nature. But, as he continued detailing some of the calamities that had befallen him, the penny dropped. Having spent over 25 years supporting disabled students, I was sure Chris had a mild learning disability.

Sitting on that train, I listened aghast as Chris told me how he had once worked for a "bad man" called John Rooney who had kept him in a dilapidated caravan and only fed him when he worked. Chris eventually "escaped".

In 2019, the number of potential victims of modern slavery rescued and referred to the Home Office reached 10,627.

It would be good to know what percentage of this total had learning or mental health disabilities. But, surprisingly, nobody knows. Although most agencies that fight modern slavery keep data on gender and country of origin, no-one is counting victims with a disability.

The one exception I found is Nottingham City Council, which reports almost 60% of its clients had a disability and/or mental health/cognitive impairment in 2019 and 2020.

'Statistically hidden form of abuse'

Other agencies acknowledge a significant overlap between modern slavery and disability.

The Anti-Slavery Coordinator at The Passage, a London-based homelessness organisation, told me: "At least 13 of the 73 potential victims we've identified in the last two years show clear signs of a learning or mental health disability - and the actual number may be even higher."

The coordinator added: "Disabilities may sometimes be hard to spot, as these clients present with complex traumas related to both their exploitation and homelessness."

At the Ann Craft Trust, a national charity combating the abuse of disabled children and adults, Deputy CEO, Lisa Curtis, believes "the modern slavery of people with learning disabilities is a statistically hidden form of abuse".

She says: "Data-capture needs to include learning disability to highlight the scale of the problem. More research, training and work are required to ensure that people with learning disabilities are protected from modern slavery and supported in their recovery from its traumatic effects."

Mencap defines a learning disability as "a reduced intellectual ability and difficulty with everyday activities," such as household tasks, managing money or socialising, "which affects someone for their whole life".

Thus, victims may already have been struggling to take adequate physical and emotional care of themselves, before being lured into exploitation by promises of food, shelter and emotional support.

Some may already have been abused as children, making them susceptible to trauma-bonding - a process in which victims are alternately praised and made to feel worthless. Others may have reduced communication skills, making it impossible for them to describe their situation to the police.

The Passage, told me how "on cold, wet nights, vans cruise well-known gathering points for London's homeless" and "well-dressed men emerge, offering kind words, bottles of wine, food and promises of accommodation and work for cash-in-hand".

Traffickers are often psychologically astute in how they groom victims and Curtis describes how, "grooming often mimics a genuine relationship".

She says: "Early in the process, the groomer may appear friendly, whilst sizing-up the psychological vulnerabilities that'll get a victim on board. For example, by saying they'll treat him like a son, they may play on a victim's emotional needs and create a sense of dependency and loyalty.

"Later - even if the victim realises they're being mistreated - they don't leave because they're emotionally dependent, fearful of repercussions or feel embarrassed that this has happened to them."

For years, Archers' slave-master Philip Moss has successfully deceived everyone in Ambridge, including his new wife.

He is a respected member of the community and when Philip's conscience bothers him, he deceives himself with the idea that he's "doing those lads a favour by taking them off the streets".

But, like other traffickers, Philip specifically targeted people who were rendered homeless by their disabilities and a failure of support services. And, in March, due to a lack of supervision, one of the men broke his back in a workplace accident.

'Odd hours'

It is a situation The Passage is familiar with. Its Anti-Slavery Coordinator told me about the case of a 55-year-old man with schizophrenia who had been homeless since he was 18.

"A family approached him when he was sleeping rough in London, offering him food, shelter and work in construction and farming. He was exploited for decades by this family, who mentally and physically abused him and moved him around the country to avoid detection.

"One day, he suffered a serious workplace injury, which led to the family abandoning him in a parking lot because he could no longer work."

Experts agree that increased public awareness is crucial in combating such practices.

Curtis advises looking out for "groups of people accommodated at unusual locations and being picked up and dropped off at odd hours".

And, when having building work done, she asks householders to watch out for labourers who "appear neglected and malnourished, have untreated injuries and who are either uncommunicative or not allowed to speak for themselves".

The Archers' modern slavery story has more surprises in store for 2021. But, for now, it's created a space to think about an extremely hidden group of individuals who are failed by society before being further devalued and traumatised by criminals.

For more disability news, follow BBC Ouch on Twitter, external and Facebook, external and subscribe to the weekly podcast on BBC Sounds.

- Published25 May 2020

- Published12 September 2017

- Published5 April 2016