Rett syndrome: My sister and I have never spoken

- Published

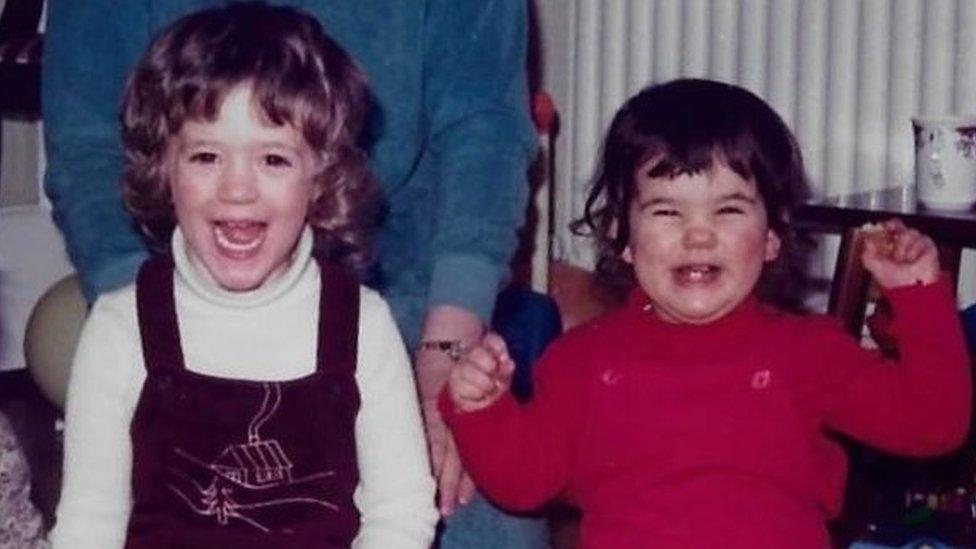

Siblings often enjoy an unbreakable bond having grown up together and shared the same experiences. That's the case for author Victoria Scott and her sister Clare. Clare can't speak, write or sign due to Rett syndrome so they have been communicating for more than four decades without words. Victoria explains.

It's 1989 or thereabouts and I'm being bullied at school. I don't want to talk to my parents about it because I'm ashamed, but I know Clare won't judge me.

After lights-out, I clamber into bed with her. We lie nose-to-nose, and she listens as I unload my worries and, when I'm finished, her shallow, rhythmic breathing lulls me to sleep.

We had many nights like this during childhood. They were entirely one-sided, because Clare can't talk.

She has Rett syndrome, a complex neurological disorder that has left her profoundly disabled. There was no sign of her condition at birth, but a faulty gene stole the skills she had developed as a toddler and she now needs round-the-clock care.

What is Rett syndrome?

It is a rare genetic disorder that affects brain development and results in severe mental and physical disability.

It mainly affects girls and impacts about 1 in 12,000 births each year

It is present from conception but usually remains undetected until the child - often from the age of one - starts to regress

Source: NHS, external

Diagnosed in the 1980s, Clare was one of the first children in the UK to be given that label by doctors who didn't have much experience to go on. This meant my parents were given two vague and frightening pieces of information.

Firstly, they were told to take Clare home and "keep her happy," inferring that she would surely die soon. That prophecy has not come to pass, thank heavens. Clare is now 41 and lives in a friendly residential care bungalow run by a charity. Our mum, Yvonne, gave up her career to care for her, but as Clare got older and her needs became more complex, even that wasn't enough. Caring for Clare takes a village.

The other thing my parents were told was that, most likely, Clare would forever have the understanding of a baby.

I have always doubted that assumption.

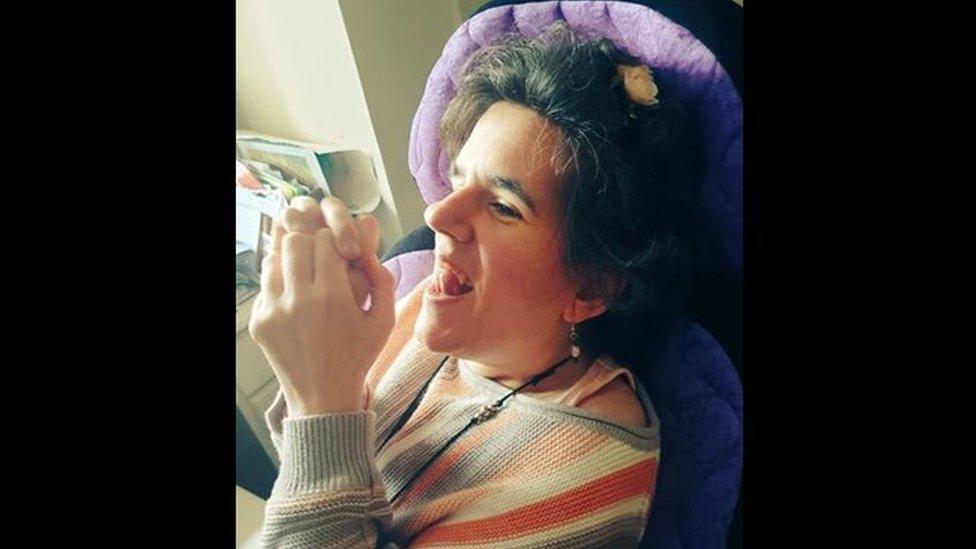

Clare's eyes are wise, warm and expressive. They light up when she listens to her favourite music - Kylie - and she is moved when she listens to The Snowman. Her eyes dance when she sees her niece and nephew and sparkle when she sees a man she fancies (including my husband, who I don't mind sharing). They also sharpen when she's in pain, narrow when she's frightened and dull when she's tired.

Then there are her hands, which Rett syndrome has characteristically made her wring daily since babyhood. They are bellwethers for her mood - frantic when she's excited, languid when she's relaxed, rigid when she's uncomfortable.

Despite her inability to communicate by the spoken or written word, these involuntary movements tell us a great deal.

In recent years, the development of eye-gaze technology - where a person can build words and sentences by focusing on a computer screen - has transformed the lives of many people with Rett, giving access to an internal world once thought to be lost forever.

Families have found that their children understand more than those doctors had originally surmised, bringing about profound change for everyone concerned. One father, whose daughter has Rett syndrome, told me her first words via eye-gaze were: "I love you".

Sadly, Clare hasn't mastered the technology, primarily because her healthcare needs have been all-consuming in recent years. She was hospitalised with pneumonia and sepsis in 2019 and Covid-19 has meant she was forcibly withdrawn from the outside world to shield.

We're not giving up hope, though, because hope is the engine that keeps driving us forwards.

There's something else spurring us on. Nearly four decades after Clare's diagnosis, we now know which gene causes Rett - MECP2 - and American scientists are expected to launch the first human trial of gene therapy, external to treat the condition next year.

This involves injecting a modified virus into the recipient which carries a correct version of the faulty gene.

Trials of the therapy on mice have demonstrated that a complete reversal of Rett may be possible. It's an extraordinary prospect - absolutely dumbfounding that Clare's condition could, potentially, be reversed in adulthood.

It feels like science fiction, even though it could soon become science fact.

I do have some significant concerns, however. I worry how Clare might feel about it, and whether she would be frightened. Furthermore, gene therapy is new and risky. What if it goes wrong?

We've also discussed the possibility of gene therapy as a family, but we are yet to reach any conclusions. Making a decision as enormous as this on my sister's behalf, without being able to consult her, is a huge responsibility.

Although research points to potentially incredible gains, gene therapy also carries some significant risks, including the possibility of developing cancer, or an immune system problem, and even the risk of death. What right do we have to make this choice for her? But also, do we have the right to deny her this chance?

It was these questions that inspired me to write my first novel, Patience, which explores how a family deal with the decision to enter their daughter into an experimental gene therapy trial. I wanted to examine the ethics and emotions that surround such a decision.

The novel is told from the perspective of Patience's mother, father, sister and, crucially, from Patience herself. She is unable to communicate, and her family are unaware that she understands.

Clare herself has had a lifetime of people making decisions about her life and her health without anyone consulting her, and I wanted to put that experience front and centre.

Back once more to those childhood nights. In those moments, when it was just the two of us, I swear I've experienced telepathy. Our faces cheek-to-cheek, I have felt words cascade into me, warm and wise.

You might suggest that it was wish fulfilment, that I was projecting my own words onto her, and that's the most likely explanation. But I also believe in the power of human love to cross barriers, to influence things beyond the realms of scientific understanding.

Maybe Clare is "speaking" to me, maybe she's not, but some evidence is irrefutable. I know from her smiles and her laughter that she knows who I am, that she remembers our bond and that she enjoys my company.

Recently, I saw Clare in person for the first time in 18 months - the longest we've ever been apart.

Once I'd wiped away a few tears, I held her hand and gave her a hug and we both reassured each other that we were still living and breathing.

Then I showed her a proof copy of the novel, which she knew I'd been writing - but probably, like pretty much everyone (including me) - never believed she'd see in print. We exchanged a meaningful look and a smile, and it meant the world to me.

Patience by Victoria Scott is published on 5 August

Related topics

- Published24 November 2011