Poor housing affecting disabled children's health

- Published

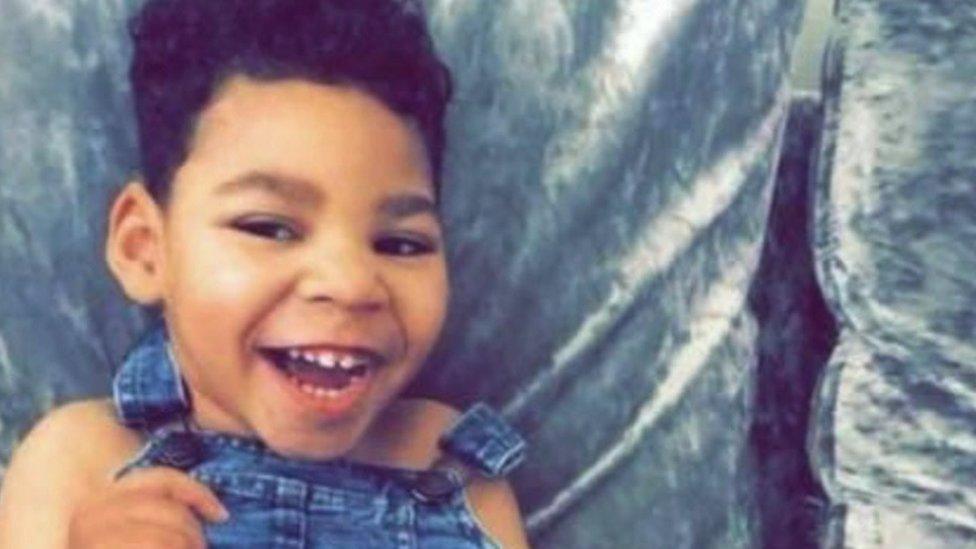

Anderson, pictured here with his mum, spent months in hospital waiting for appropriate housing

For mum Princess Bell, the one time each week her children spend together is very special.

But the siblings don't live separately. They're in the same house - but they can't spend more time together because a combination of their disabilities and unsuitable accommodation means they have to stay on different floors.

They are one of the 4,100 families who responded to a survey by the charity Contact surveyed in June and July of this year.

Parents of disabled children reported worries that inappropriate housing was having a negative impact on their health.

More than 40% who took part in the poll said their home didn't meet their child's needs.

Speaking to BBC Newsnight, some parents even said they struggled to even get their children in and out of their property.

Princess lives in temporary accommodation in south London with her 13-year-old son, 11-year-old daughter and a baby.

The older children both have a rare genetic condition that means they are unable to walk or speak and have breathing problems.

The family are living in a three-bedroom house - every inch of each room packed with specialist equipment - while they wait for the council to find them a new home.

Due to a lack of space, the two older children with disabilities sleep on different floors. Once a week, Princess takes one child up to see the other. She says she doesn't feel safe doing this more often.

"They've always been very, very close. And they're in the same house and they don't see each other... so when it's then time for her to go back to her room, she cries and they lay together on the mat entwined because they're best friends and they don't see each other and they're in the same house. And it is heartbreaking to see that because we're already housebound."

Lambeth Council said it had been working hard to meet the very complex housing medical needs of the family and apologised for delays in resolving the issue.

"However, we face a real shortage of available homes," said a spokesman.

Window of opportunity

Data from Contact's survey, shared with Newsnight, suggested 27% of respondents said they felt their home made their child's condition worse or put them at risk.

"We were really taken aback by the proportion of families who weren't only saying that the housing was unsuitable, but that their home environment was actually having a negative effect on their child's disability," said Amanda Batten, Contact's chief executive.

"There's no doubt that poor and inappropriate housing is having a hugely detrimental impact on the health and the lives of many disabled children and their families," she said.

While the majority of the respondents lived in private or privately rented accommodation, 31% lived in social housing.

The government has been consulting on improving access to accessible housing. The report is due in December.

Campaigners say this is a vital opportunity to drive up standards of housing and potentially transform the lives of some of our most vulnerable children.

Amanda Batten says there's a window of opportunity for change.

"Fundamentally, the problem is that there is not enough social and affordable housing full stop and, in particular, not enough social and affordable housing that is accessible to disabled children and their families," she says.

And the lack of housing is costly to other sectors.

The government's own data shows that delayed hospital discharges cost the NHS about £285m per year and the evidence suggests that up to 14% of these delayed discharges could be reduced by accessible housing.

Many disabled children need extra space for equipment such as wheelchairs

Bertille Chuipa's son Anderson, now 16, had a head injury while go-karting. He uses a wheelchair and needs a lot of space for his medical equipment.

Bertille gave up her job as a teacher and translator in Manchester to look after Anderson. "He needs somebody all the time at his side to keep an eye on him," she says.

Anderson's former home wasn't suitable for a wheelchair and he spent more than a year in hospital while the council looked for an appropriate property.

Tara Parker, a paediatric nurse who works for the charity WellChild, says its research shows Anderson's experience isn't that unusual.

"Some young people will be delayed in an intensive care unit for approximately 12 months. And the cost of that is eye-watering. You could have bought and built them three houses by the time you've done that," she says.

Local authority money is available to make improvements to properties, but the charity says it has more than 700 families on its waiting list for property improvements, 90% of whom live in social housing.

Manchester City Council said that occupational therapists searched for some months to find an appropriate home for Anderson due to the size of the wheelchair in question.

The family's current bungalow has been extensively adapted.

At its starkest, inadequate housing can play a part in the circumstances surrounding a child's death.

Newsnight has been investigating the reasons behind the deaths of young people, using evidence generated by the country's first national database of child deaths, the National Child Mortality Database, which was published in May.

Poor housing was identified as a contributing modifiable factor in child deaths in this country.

In 2016, Mollie Wells's son Harlie was born with a brain injury and cerebral palsy. Mollie, who lives in Ipswich, was only 17 at the time and was responsible for the majority of his care.

"He needed round-the-clock care. He couldn't walk, talk, couldn't sit up," she says.

Harlie's mum wasn't able to fit his wheelchair inside the flat where they lived

In 2017, Harlie and Mollie had to move after her private landlord gave her notice. The council found them a flat but the wheelchair wouldn't fit through the door and had to be left outside in a communal area.

"I had to lift him everywhere. I had to do ground lifts. I had to do everything because he had no equipment," Mollie says.

The lack of space and equipment in the flat meant Mollie couldn't follow his care plan or medical advice properly.

"He couldn't do physio, which possibly could have strengthened his legs, his back, his posture," she says.

Harlie's doctors and occupational therapists wrote to the council to say he needed to be rehoused urgently.

"They [the council] said that they'd look into it and it went on for two-and-a-half years," Mollie says.

In October 2019, Harlie died unexpectedly. Mollie found him in his bed. She tried, in vain, to resuscitate him. Harlie was five years old.

The conditions surrounding his death fed into an analysis by experts on the national child mortality database.

Jacquelyn Wood is an NHS child death review nurse who looked at the circumstances around Harlie's death to see what lessons could be learned.

Ms Wood says they looked at the impact that the pressure of being carried throughout the property might have had on his body. "And I think it's really about asking that question. Does that then affect kind of life expectancy and mortality?"

She says Mollie fought to give Harlie the best care that she could afford and could access.

"When it came down to housing, there wasn't anything else that she could do," she says.

"It really isn't an isolated incident.

"Ultimately the problem we have across the whole of the UK is there isn't enough suitable disabled housing to meet the needs of these cohorts of children," she says.

Mollie also believes his housing affected Harlie. "He wasn't given a chance," she says.

Ipswich Borough Council said it had provided the best accommodation it could for Harlie Beau-Wells.

But "it was acknowledged by all… that the property did not meet all of Harlie's needs".

It said it was building a specifically adapted bungalow for the family when Harlie died.

"Like all councils with housing, we have a large shortfall of suitable adapted property to meet demand from people with needs due to their disability," a spokesman said.

The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government told Newsnight: "We recognise the importance of improving accessibility, and the number of accessible homes has nearly doubled in a decade.

"Since 2010, we have invested over £4bn into the Disabled Facilities Grant, providing adaptations to almost 450,000 homes, including stairlifts, wet rooms and ramps. Councils are best placed to decide how much accessible housing is needed in their area, and set these requirements in their local plans."

Watch the full report on BBC Newsnight on BBC Two or catch-up later on iPlayer.