Winter Paralympics: The lowdown on being disabled in China

- Published

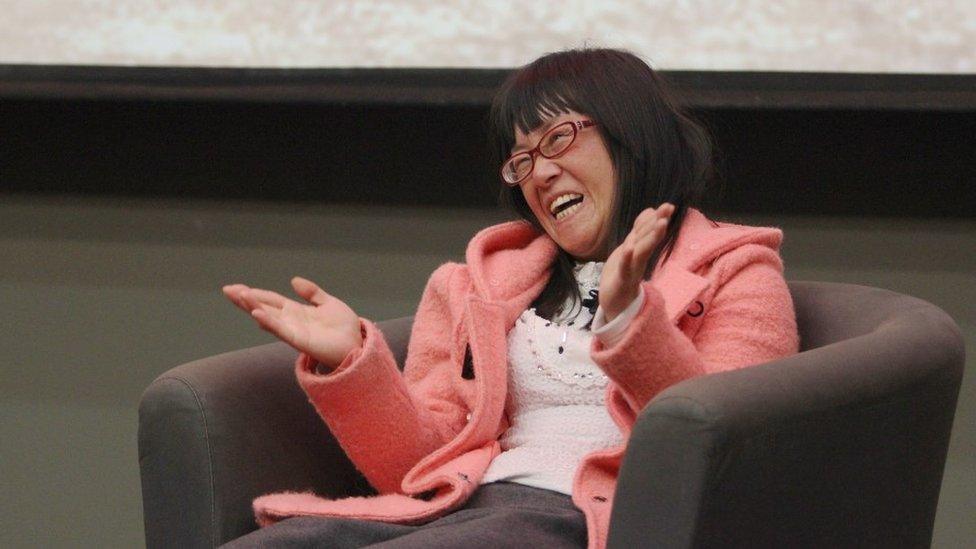

Poet Yu Xiuhua became a big hit after she published poems which reframed the way China thought about disabled people

From an outrageous poet to grassroots activists living in an "atmosphere of fear", get the lowdown on disabled life in China as the Winter Paralympics get under way in Beijing.

In 2014, a poem full of sex and lust appeared online. It was posted by a Chinese woman who had published work before but none had gained traction quite like this.

Crossing Half of China to Sleep With You was its title, the author Yu Xiuhua, a farmworker with cerebral palsy. It lit-up the internet - the nation couldn't believe a disabled woman was talking about wanting sex so explicitly.

"People started to pay attention to her," says Hangping Xu, an expert on contemporary disability culture at the University of California, Santa Barbara, USA.

"She has desire, she's playful, she's using dirty language. She doesn't fit into the state-sponsored narrative about people with disabilities always being very nice, obedient, inspiring people."

Yu felt it was time to remind everyone that disabled people are complex human beings, not one-dimensional.

Jia gets that. She is 26 and grew up in Guangzhou, south China, before she moved to Beijing. She has Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a muscle wasting condition, and uses a wheelchair.

"People tend to think that we will be positive everyday and have a smile on our face, but actually people with disability also have times that they are sad and angry."

As a child people made comments about Jia. They were "not discriminatory", she says, but curious.

At the time it wasn't common to see disabled people in the street but Jia believes people are more familiar with their presence now - "In Beijing, every time I take the underground, I see people using wheelchairs".

For China, 2008 was a big year for disability. It hosted the Summer Paralympics and ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities which commits the country to "fundamental freedoms" such as a right to education, employment and accessible transport.

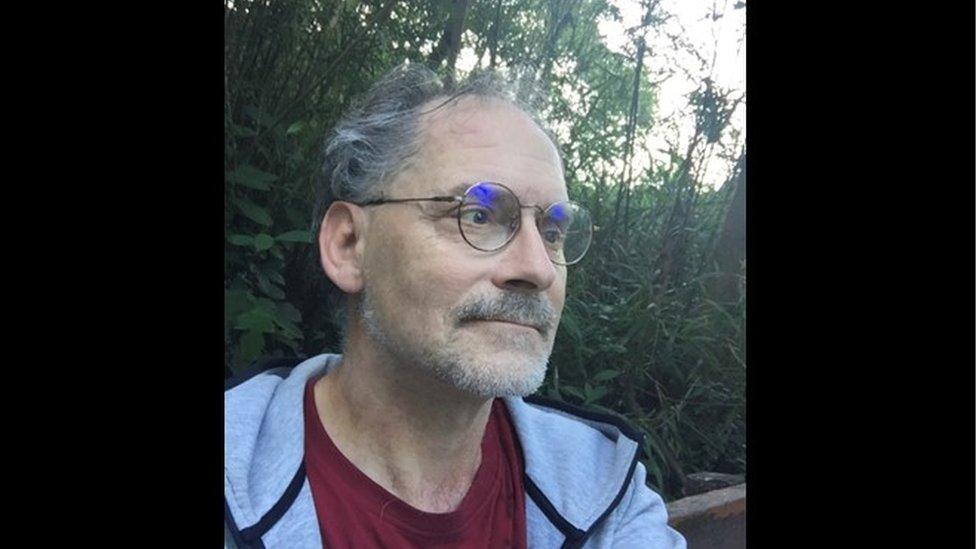

Stephen Hallett, who has a visual impairment, has lived and worked in China for 30 years. He is a specialist in disability affairs in China, chair of the UK charity China Vision and visiting professor at the University of Leeds.

He says the changes in 2008 signalled "a slow trajectory towards a more progressive, more humane society".

It was a change from the early 2000s when "disabled people were hidden either at home or in the countryside."

More access provisions made it easier to go out, which raised their visibility as regular citizens.

'Atmosphere of fear'

Then progress unexpectedly stopped.

After President Xi Jinping came to power in 2013, civil society, which allowed people to call for change, was "largely closed down", Stephen says. It was exchanged for what he calls an "atmosphere of fear, where people can't speak out and criticize the government.

One of the most notable organisations to close was Yirenping, which defended the rights of disadvantaged groups through legal means.

It had built a network of disability rights activists to support employment, education and accessibility cases. But from 2013 its offices were raided, its activists jailed and all operations ceased.

"The trouble is you don't bring about real change unless you have voices and a degree of activism from the grassroots," Stephen says. "China is in a state of stagnation."

Without that activism, progress has become piecemeal.

Jia attended mainstream school but it didn't meet her needs. There was no accessible toilet on the campus which meant she had to use a temporary toilet in view of other students.

Friends of Jia complained about the "embarrassing" situation and the school, never having thought about it before, built an accessible one.

The same thing happened at Renmin University in Beijing where she studied world history. She had to build upon the changes others had made before her.

The room she lived in already had a ramp thanks to the previous disabled occupant and Jia's teachers agreed to move classes out of inaccessible buildings so she could attend.

Although it shows a willingness on an individual level, there is no legal framework to require it.

Hangping believes it's because disability is still seen as charity.

"There is nothing about the notion of thriving and how the institution should provide these accessible facilities and the state should invest in this," he says.

In 2006 the China National Sample Survey on Disability found the disabled population stood at 83 million, or 6.34% of the total 1.3 billion. While the figures have slightly increased to 1.4bn and 85 million respectively, they are likely to be on the low side as the World Health Organisation says the disabled population of the world is 15%.

The survey revealed another statistic - half were aged 60 or over, a group that is only set to get bigger and develop more needs.

That plays on Jia's mind and she hopes to become a professor of public policy.

"I was treated well, but I would like to do more research about the environment for disabled people because there are many big problems, like finding jobs," she says.

Globally, disability employment tends to be low and China, despite its communist background, is no exception. Like several countries, including Japan, it uses a quota system. Companies must employ 1.5% registered disabled people or pay a fine. Many choose to absorb the fine.

Proceeds from the fines are then used to support disabled people into the workplace

But some businesses abuse the system. They employ disabled people without expecting them to actually work so they don't have to meet their access needs. It means an income for the individual and government statistics look good, but it doesn't bring about meaningful change or fulfilment.

Jia says the quota system often discriminates against those who need carers or reasonable adjustments but, she says, the internet has become a platform full of opportunities which the pandemic helped consolidate after many could not attend the office.

One of her disabled friends, who needs to rest every few hours, set-up an English tutoring business which "helped him achieve his dream" from home. Others have gone into online writing jobs.

But finding work relies on education and qualifications which is another challenge.

Children are entitled to an education from "kindergarten to senior high school" according to China's State Council, but this doesn't always happen.

Those with physical disabilities are more likely to access mainstream education while those with learning or sensory disabilities often find themselves in specialist schools with their own curriculums.

"This kind of segregation can be problematic," Stephen says. It limits future prospects and perpetuates low expectations.

Students at blind schools are often funnelled into the "default career option" of massage - a big part of Chinese culture and it's accesible work if you can't see.

"The people who have been given good jobs in hospitals can earn serious money," he says, but there's an "underbelly" which can make women especially vulnerable.

"There's a whole sex industry there. It's hard to get to the bottom of because it's one area that everybody knows about, but they don't want to talk about."

While there are problems, he says education has improved and more disabled people are going to university but for those unable to go, or who can't find employment, family is key to their care.

The China Disabled Persons' Federation is one state-owned organisation that aims to represent the rights and interests of disabled people.

Its current chairperson, Zhang Haidi, became paraplegic aged five and uses a wheelchair. Unable to access school she taught herself to university level and learned four languages. She is somewhat of a legend in China and also head of China's Paralympic committee.

But despite the Federation, only the most seriously disabled receive financial support from the government. Instead, the focus is on reducing poverty by providing a minimum welfare subsidy known as "Dibao". By default this often provides financial support to disabled people who are too often living in poverty.

For families who don't qualify for Dibao, tough decisions have to be made.

Jia has 24-hour care. She receives a monthly sum of 900 Yuan (£106.57) from the government while her family pay the majority remaining cost of 4,100 (£485.70). She considers herself lucky.

"If they don't hire a helper for me that means my mom will not go to work but stay at home and take care of me."

She knows of families where the cost of care has resulted in parents losing their careers.

One father, a successful businessman, left his job to care for his daughter with SMA, while his wife looked after their autistic son.

Jia says it's one area of support she wants to see improved.

"There is some funding for disabled families, but it's not enough. If that family had enough money to hire a helper maybe the father can go back to his business and contribute more to society."

That idea of contribution remains prominent.

The Communist Party of China has ruled since 1949, and the concept of the "ideal citizen" prevails: "A non-disabled man who's able to contribute to the motherland," Stephen says.

It's an ableist ideal, but notions are shifting.

Earlier this year the government started funding a drug for SMA patients which was previously too expensive for Jia to contemplate. Within a month of taking it she could once again stand-up unaided.

She says while the expense is a financial "burden" for the government, she was touched and excited for the future when a spokesperson said it was because "every minority group is priceless".

There are hints of progress but equality is a long way off - something the government itself is recognising.

Recently, the State Council described progress as "unbalanced and inadequate" with a "big gap between the lives these people lead and lives to which they aspire".

"We have a long way to go," it admitted.

Related topics

- Published5 October 2022

- Published15 April 2015