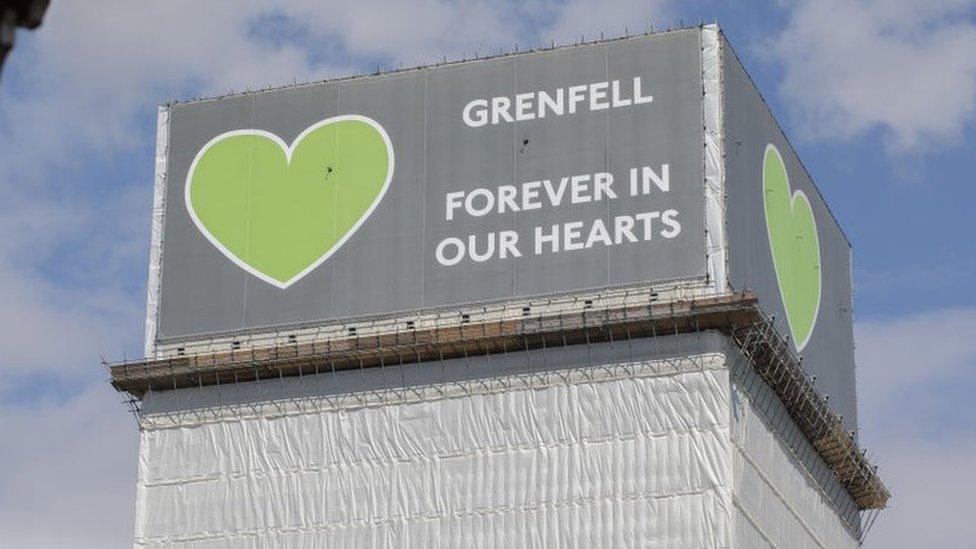

Grenfell fire and PEEPs: 'I want to escape a burning building, not sit and wait'

- Published

Fleeing a burning building is a natural instinct, but for many disabled people it might be impossible to get out unaided. Following the Grenfell Tower fire, recommendations were made to create evacuation plans for residents who need extra assistance to escape, so why did the government go against it?

When Joe Kimber goes to bed at night he worries about what will happen if a fire takes hold of his block of flats.

The west Londoner lives on the third floor with his partner, Liz. Following a complex brain injury he struggles to walk, often uses a wheelchair, and is unable to get up if he falls. It begs the question - how would he escape in an emergency?

"If there's a fire, there's no plan to get me out the building. The fear of being cremated alive is horrendous," he told the BBC Access All podcast.

This is a fear for many disabled people in high-rise flats who would be unable to escape without extra assistance. Currently, there is no legislation ensuring they can get out safely and instead they are told to "stay put" and wait for help.

Last week that fear intensified when a recommendation to make it mandatory for building owners to arrange evacuation plans - known as PEEPs - was turned down by the government.

"I find it mind-boggling that we're having a conversation about getting disabled people out of a burning building" Joe says.

The recommendation to introduce PEEPs had come from the first Grenfell Tower Inquiry (GTI) report which looked into the circumstances of the June 2017 fire, where no evacuation plans were in place.

It found that the "stay put" advice - which works on the premise that it is generally safer to stay in a flat where the walls, floors, and doors are designed to contain fire - had failed because the ACM cladding had acted as a source of fuel.

But when it was realised "stay put" was ineffectual, there was no time to help people escape.

In total, 72 people lost their lives, including 15 disabled residents.

Grenfell United summed it up by saying: "It left them with no personal evacuation plan and no means of escape. They didn't stand a chance."

The GTI report advised the government to place a legal obligation on building owners to implement Personal Emergency Evacuation Plans or PEEP.

A PEEP is a tailored plan between an individual, who cannot get themselves out of a building unaided, and the person responsible for fire-safety. It is often used by those with mobility issues, cognitive, visual or hearing impairments.

At its most basic, it's a conversation about the safest route out of a building and might simply include ensuring a deaf resident has an appropriate alarm.

Crucially, it is about quickly evacuating rather than waiting for the fire service to rescue you when they arrive.

Many disabled people will be familiar with PEEPs as they are a legal requirement in the work place - failure to have one breaches the Equality Act 2010 and is considered discrimination.

But it isn't required in residential blocks.

Georgie Hulme in an evac chair

The Grenfell inquiry's recommendation then, was a hope for many disabled people. A follow-up consultation last summer backed the inquiry's findings as 83% of respondents - including building owners and construction companies - agreed PEEPs should be implemented.

But last week the government announced it would "propose to deliver against the Grenfell Tower Inquiry" and the subsequent consultation, on PEEPs.

"We are utterly appalled," says Georgie Hulme, co-founder of Claddag an organisation fighting for PEEPs to be made mandatory. "Why undertake any consultation or public inquiry, if the results or recommendations are just ignored?"

Georgie herself, who acquired her disability as an adult, experienced a "near-miss electrical fire" and says having no way out of the building was "extremely frightening".

"I felt sick. I thought, how would firefighters rescue me if needed? Would there be an evac chair? If not, would they carry me?

"Being rescued should never be the first and only option. Disabled people should not have to wait, while others who don't need any support to evacuate get out of the building."

The government cited practicalities as the stumbling block behind implementing PEEPs. It said it would require "staffing up" buildings to ensure the plan is carried out, but that would cost about £21,900 per building per month.

It added that a single member of staff "would be unlikely to successfully evacuate" all mobility impaired residents and another alternative - relying on neighbours - might cause tensions between disabled and non-disabled residents.

It also added that attempts to evacuate disabled people before the fire service arrived might hold-up non-disabled residents trying to get out.

"We're talking about whether somebody is going to lose their life for the sake of a couple of hundred pounds or a conversation," Sarah Rennie, Georgie's co-founder of Claddag, says. "A lot of disabled people across the country are very frightened."

She says, while some might question why disabled people would choose to live in tower blocks, there is often little choice when it comes to housing stock and affordability. People might also choose to live as close to work as possible or near their support network.

After deciding against the plan for PEEPs, the Home Office has launched another consultation for an "alternative package" known as Emergency Evacuation Information Sharing (EEIS).

This would involve a risk assessment by the fire service with the building manager involved. Any safety measures suggested, such as handrails, would generally be financed by the resident.

But it would only apply to buildings assessed as "higher risk". London Fire Brigade says about 1,000 buildings in the capital, roughly half nationally, are classed as higher risk. All other buildings would continue to use "stay put".

Sarah says: "This concept is really worrying. The responsibility is being passed to the fire service. It's not evacuation, it's going to be rescue."

She is also concerned about sharing sensitive health data and the fact that while you wait for the fire service to help you "your chance of survival drops significantly" when an evacuation plan would already have you outside.

According to the Home Office, the average time from 999 call to the first vehicle arriving at a fire in England last year was 7 minutes and 3 seconds.

Sarah also adds that while her notes might explain she has osteoporosis and needs to be lifted in a certain way the nature of the emergency means the fire service won't be able to consider such intricacies on arrival and she could be injured.

"The fire service in a rescue is frankly not going to care because they're going to try and save my life," she says. "This is unworkable and it's not fair to the fire service."

With its new plan out on consultation until August, the government says it has so far incorporated 21 of the 46 recommendations from the GTI into law, including setting minimum frequency checks on fire doors.

A Home Office spokeswoman added: "Our fire reforms will go further than ever before to protect vulnerable people."

But campaigners already see this as a U-turn after Boris Johnson made a pledge to parliament in 2019 in which he stated: "I can assure the house and all those effected by the Grenfell tragedy that where action is called for action will follow."

You can listen to the podcast and find information and support on the Access All page

- Published19 May 2022

- Published16 May 2022

- Published20 January 2022

- Published14 June 2020