Self-help plan to make the streets safer

- Published

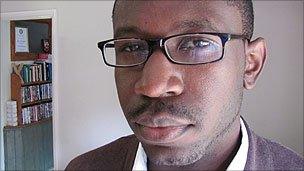

Al Patel has made his shop a place where youngsters can seek help

How do you make the streets safer for young people? It's painfully easy to see the problem, with the sad litany of knife crimes punctuating the news bulletins.

But what's the answer. Tougher penalties? More police? Ever more elaborate surveillance technology?

An innovative project in London is experimenting with a form of community self-policing.

It involves shopkeepers offering their shops as "safe havens" - so that any youngsters who think they are under threat can run inside and seek shelter.

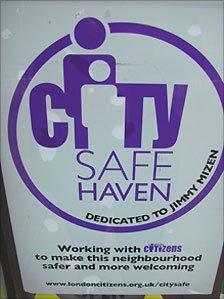

There are stickers identifying these unofficial shelters. It is a simple and direct answer to the need for teenagers to have somewhere to turn for help.

It is very much in keeping with the "big society" ethos, in which the Cameron government wants communities to take responsibility for themselves, rather than looking for the state to intervene.

The CitySafe project is being developed by the London Citizens community group, as a grassroots approach to tackling violence and increasing the safety of young people.

Its most prominent spokesman is Barry Mizen, father of Jimmy Mizen, a 16 year old murdered near his south London home in 2008.

Protection

Mr Mizen says the driving force was his local community's need to find a way to respond to the shock of Jimmy Mizen's death - and the realisation that any change would need to come from within the community rather than the intervention of any outside agency.

"Safety won't come from government legislation, the police can't always be there. We have to build up the community. It's strong communities that are more likely to be self-regulating," he says.

Barry Mizen developed the idea of safe havens after the murder of his son, Jimmy

The practical strategy being developed is to create places of safety in local high streets where youngsters under threat can get help.

Shopkeepers are asked to display a CitySafe sticker - and make a commitment to lock the doors and call the police if anyone needs their assistance.

These stickers are now in many of the windows in the parade of local shops in Lee, south London, where Jimmy Mizen was killed.

There are 200 such CitySafe sites across the capital, including shops, restaurants and City Hall. And the idea seems to be about to catch on much more widely.

There are plans for similar projects in other big cities. Railway stations could be designated as safe havens and Mr Mizen says he has been talking to major supermarket chains about their possible participation.

An increasing number of primary and secondary schools are getting involved.

But when Mr Mizen talks about the project, the language is very different from the usual vocabulary of crime fighting.

The word that keeps cropping up is "relationships". It is the idea that improved safety comes from strong relationships in a neighbourhood.

The London Citizens group first build up a relationship with local shopkeepers, asking them to talk about their own concerns and experiences of crime and anti-social behaviour.

Building links

It is a deliberate process, with its own protocol, including asking shopkeepers to record and report 100% of all incidents of crime affecting themselves and their neighbourhood.

Derron Wallace wants to see the community establishing its own safer streets

"You have to build up this relationship, talk to them about the crime that might often go unreported," he says.

Once this communication has been established between local people and local shopkeepers, individual shops are then asked to take on the status of a CitySafe site, with a commitment to protect any youngster who needs to shelter there.

These links are sustained - and in Greenwich, where dozens of businesses have recently signed up - school children delivered flowers to shopkeepers, as a symbol of this relationship.

There is an evaluation underway which will measure its effectiveness. But its success will be measured more by what does not happen, then what does.

London Citizens local organiser, Derron Wallace, describes how a girl asked for help in a nearby restaurant that is part of the CitySafe scheme.

The men who were threatening her were hanging around outside - so a manager called the police and stayed with her until she was safely able to leave.

No headlines, as nothing happened. But the difference in someone's life might be immense.

Who will help?

Al Patel, who runs a chemists shop in Lee, near to the Mizen's family home, has a CitySafe sticker in his window.

He says that he had been robbed not long before the fatal attack on Jimmy Mizen - and that had made him think "where's the help gone?"

There are now 200 safe havens across London, with signs in the window

Getting involved in CitySafe had created a beneficial "domino effect", he said, with these community links giving him a greater sense of security. "It's about working together to feel safer."

Building up relationships with local people, shopkeepers and the police meant that otherwise isolated individuals could support each other.

"There used to be drug-dealing in daylight," he says. Gangs of youths would hang around. But these have now been moved away by this partnership of the local community and police.

Of course there are no instant answers.

Mr Wallace says that people have become so accustomed to being afraid of crime that some do not even want to talk about it - and even if they have been abused or attacked, they might not report it.

But he says that when the impact of violent crime can be so random and destructive, affecting so many families, that it is something that can not be allowed to be accepted as inevitable.

Our responsibility

This scheme supported by Mr Patel and the other shopkeepers is a very different philosophical approach from the usual debates about law and order.

It is based on the idea of building up safety from the roots, rather than a top-down tinkering with the machinery of government. It is organic rather than genetically modified crime fighting.

"It can seem very daunting for an individual to try to change something, but the community working together can really begin to make inroads," says Mr Wallace.

It is also significant because London Citizens, part of the Citizens UK group, has become very influential.

Apart from the televised debates, a Citizens UK event was the only public meeting addressed by all three of the party leaders during the election.

Political leaders have lined up to be associated with its grassroots activism.

Mr Mizen, whose campaigning is driven by the memory of his lost son, says the extremes of violence are a continuation of the persistent, low-level, anti-social behaviour that often goes unchallenged.

"Is this how we want to live? People shouldn't be afraid to go out at night. It's not good enough," he says.

And he believes this is a problem that can only be solved by communities deciding what's an acceptable way of behaving and then finding ways to enforce it.

"Your safety, my safety, is all our responsibility," he says.